Keynote speech by Bank of Greece Deputy Governor John (Iannis) Mourmouras at the National Bank of Romania - OMFIF Economists Meeting in Bucharest (Romania) entitled: “The EU (once again) at the crossroads: this time may be different?

22/05/2018 - Speeches

Bucharest, 22 May 2018

Your Excellencies,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Allow me first of all to thank the Governor of the National Bank of Romania, Mugur Isarescu, and the OMFIF Board of Directors for the kind invitation to deliver the keynote speech at today’s National Bank of Romania-OMFIF Economists Meeting. It is a great pleasure and honour to be in Romania, a country in which the 1821 Greek Independence Revolution has its roots. Prominent Greeks originating from here helped to free Greece from four hundred years of Ottoman rule. Your country today hosts a vibrant Greek business community, which I will be addressing at the Greek-Romanian Chamber of Commerce at a dinner event tonight.

In its history of six decades, the EU has been faced with multiple crises; it came close to breaking point, but managed to overcome, for instance, the ‘empty chair crisis’, when De Gaulle refused to take part in Council meetings, the rejection of the Maastricht Treaty by the Danes or the Nice Treaty by the Irish. The solution then and now is to move continuously pedalling forward, for instance, with the adoption of the single currency, the enlargement to Central and Eastern Europe after the end of the Cold War, and the completion of EMU today.

My speech today will be structured in four sections. After a brief introduction presenting the current economic juncture around the world, I will very briefly discuss the state of the euro area economy. In the second section, I will take a look into the incomplete architecture of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) and where we stand today, highlighting the downside risks of the lack of progress on the necessary reforms and, more particularly, the populist rise. The third section will be focused on the countries of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) as candidates for euro area accession and also present the benefits of EU membership, taking a look into the EU funds received under the current EU budget and how EU financing will evolve under the European Commission’s new proposals on the new budget for 2021-2027. I will also offer my view there on Romania’s prospective euro area accession. In the final section, I will offer some remarks about my own country, Greece, which seems to be finally coming out of the woods after three adjustment programmes within the eurozone.

1. Introduction and a few remarks on the state of the euro area economy

At a global level, as I was the official representative of the Bank of Greece to IMF/WB Spring Meetings last month in Washington DC, I would like to share with you my takeaways: caution and scepticism are the two catchwords I got from the Meetings. For instance, the heightened fears about an escalation of tensions between the US and China, in light of the US decision to impose tariffs on imports on national security grounds and the US stance in the negotiations over the revision of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), more specifically, the US demands to limit imports from Canada and Mexico. Markets are sceptical about the upturn since, on top of the threat of a global trade war, there are important risks (including geopolitical ones, breeding again in the US and I am referring to the US Administration’s decision to pull out of the Iran nuclear deal undermining global stability and threatening to disrupt the global order – the oil price has risen by almost 15% in the last month). Trade wars may be avoided, but trade tensions have been having an impact on market sentiment, posing risks for the upturn in the global economy.

In Europe, expectations for near-term euro area reforms are now very low. France has been putting pressure on Germany to come to concrete decisions on deepening EMU at the June European Council, including on the Banking Union. I will come back to EMU reform in more detail shortly.

Turning now to the state of the economy in the euro area, headline inflation was 1.3% in March, while core inflation was just 1%. Euro area GDP is expected to grow at 2.4% in 2018 and 2% in 2019 and to slow down to 1.6% in 2020 and this is worrying of course for the dynamics of output growth in the eurozone. Nothing lasts for good! The unemployment rate was 8.5% in February, the lowest since December 2008. The April 2018 Bank Lending Survey for the euro area concluded that credit standards eased considerably for loans to enterprises and housing loans, and loan demand increased across all categories, thereby continuing to support loan growth. As far as the ECB’s QE programme is concerned, ECB holdings amount to €1.96 trillion under the Public Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP), while total purchases under the Asset Purchase Programme (APP) amount to €2.39 trillion, and the APP is expected by the majority of economists to come to a close by year-end. The pace of APP purchases was reduced to €60 billion per month as of April 2017 (from €80 billion previously) and to €30 billion per month as of January 2018.

2. EMU reform and the risks from the lack of progress

2.1 EMU reform

I would now like to discuss the concerns about the EMU setup, especially in the aftermath of the euro area debt crisis. The crisis brought to the surface major flaws in the euro area’s functioning, which had been building up over time and did not emerge overnight. The eurozone remains a job half-done and, without a doubt, the completion of the EMU architecture could further facilitate and motivate Member State reforms in view of euro area accession.

On the positive side, one has to mention the establishment of a permanent rescue fund, the European Stability Mechanism, which provides financial assistance to euro area countries experiencing, or threatened by, severe financing problems, which can no longer borrow money on financial markets as a result. A Banking Union is on track to be completed, ensuring centralised supervision of systemically significant credit institutions subject to a single rulebook applicable across the European Union and also ensuring centralised resolution in the event of failure of such a credit institution. A Capital Markets Union is also under way, creating a new financial system that is less dependent on bank financing with the potential to increase risk-sharing via the private sector and address economic shocks.

Although the EMU is now stronger, it is not yet fully shock-proof.

Table 1 Elements to complete an Economic and Monetary Union

Source: European Commission.

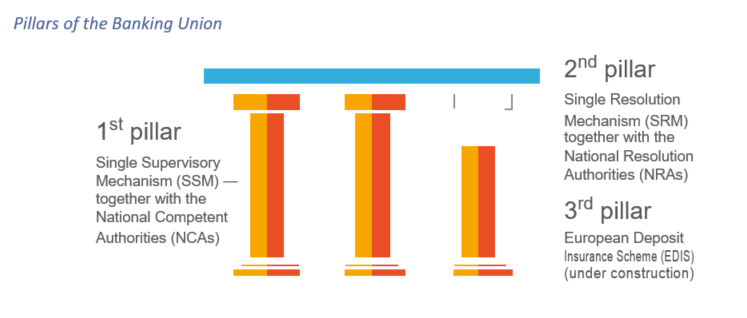

I will stay a bit longer on the Banking Union which is of direct interest also to non-euro area EU Member States. It is currently still lacking key components that would ensure risk-sharing across the euro area and break the vicious circle between banks and sovereigns. A reflection paper by the European Commission on deepening the Economic and Monetary Union proposed concrete steps that could be taken by the time of the European Parliament elections in 2019, but progress has fallen short of the European Commission’s ambitions.

Figure 1 The three pillars of the Banking Union

Source: Single Resolution Board.

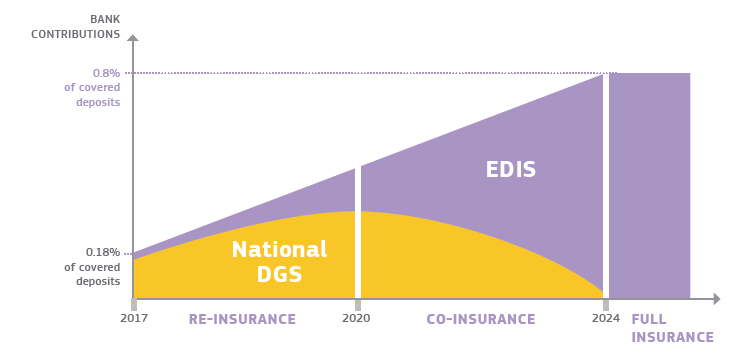

There is still no agreement on the Commission’s proposal for its third pillar, consisting of a European Deposit Insurance Scheme (EDIS), a banking union-wide scheme to be introduced by 2025, pooling funding from banks across the Banking Union to provide stronger and more uniform insurance cover for all retail depositors in the euro area.

Figure 2 The evolution of EDIS

Source: European Commission (2017), Factsheet “A stronger Banking Union”, p. 4.

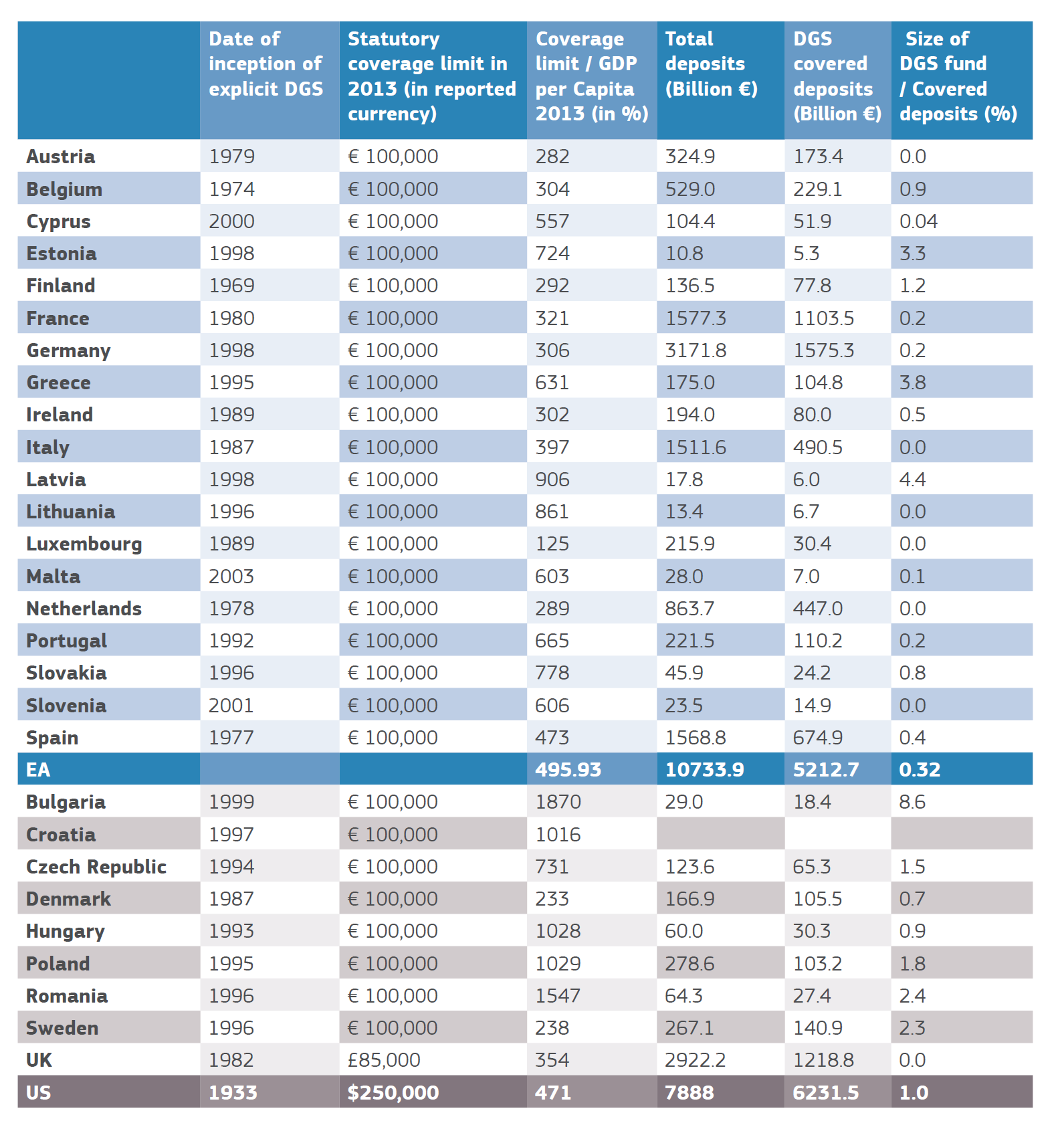

The existing Directive (2014/49/EU) on national Deposit Guarantee Schemes guaranteeing deposits of up to €100,000 also covers CEE Member States. Of course later, once EDIS is in place, a single deposit insurance fund would be of interest to CEE countries to offer deposit guarantee also through their national schemes, supported by a common pot. As you understand, this is a strong incentive to join the euro ultimately.

Table 2 Deposit Guarantee Schemes in the EU and the US (EU 2012 figures in euro, US 2014 figures in US dollars)

Source: European Commission, “Towards a European Deposit Insurance Scheme”, 9 November 2015.

EDIS requires only €12 billion on behalf of Germany to create the common pot of €38 billion, a country that is dragging its feet on the issue. French banks account for the largest contributions to EDIS, as France – keen to the idea – has the largest banking sector in the euro area, followed by Germany. If we look at these sums, we should see them as a tiny hedging against the risk of systemic bank runs.

Remember that what is at stake is a mass withdrawal of deposits in the case of a bank failure, which can create systemic financial instability. Even the announcement of establishing this common pot, would have a strong confidence-building effect on European depositors in the sense of avoiding risks of self-fulfilling prophecies on bank runs. It is one example par excellence showing how risk sharing may contribute to risk reduction. But, of course, EDIS approval is ultimately a question of political will, subject to national sensitivities. This number (€38 billion) is not even half of the one percent of the total eurozone deposits (worth more than €10 trillion today).

2.2 The risks arising from the lack of progress on reforms

There are significant risks posed by the lack of progress towards completing the EMU architecture. So far, actions have not matched the rhetoric on completing EMU with the risk of missing what may be a limited window of opportunity to introduce fundamental reforms at a time of prosperity. The euro area recorded its fastest growth rate for a decade and has been expanding robustly for more than five years, but the fog of uncertainty thickens, when it comes to growth prospects in the years ahead. The Jean Monnet principle applies: “Europe is the sum of the solutions adopted to address the crises it is faced with”. If the flaws in the design of the euro area are not addressed at this opportune time, given that the next crisis may be around the corner and the job of fixing the EMU remains unfinished, this will come with a heavy price for the single currency. The collective memory tends to remember the costs rather than the benefits of European integration.

Many people, including myself, feel that we need to strike a balance in the classic struggle between solidarity and national responsibility, or the ‘new wine in the same old bottle’, namely risk-sharing (namely mutualisation of costs) versus risk reduction. Especially in the South of Europe, there is a strong feeling that this balance is unstable and in order to make it more stable and more symmetrical; what we need are stronger European institutions. To quote Winston Churchill, a great European, “to do our best is not enough; sometimes we must do what is required”. The ultimate risk is a rise in populism and anti-Europeanism.

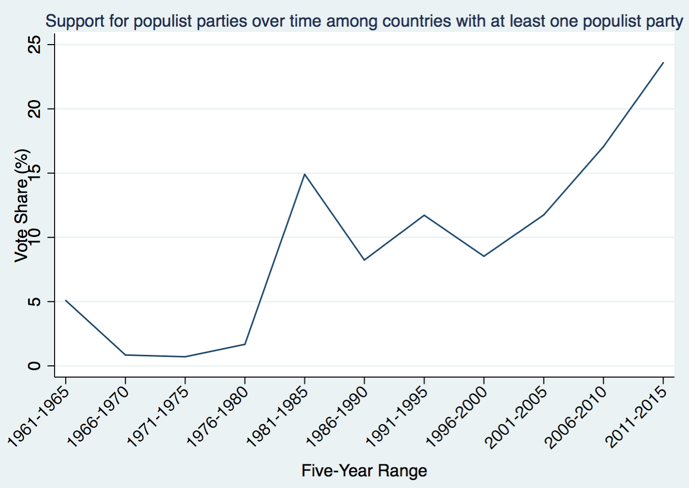

There is a rising populist trend across the world, as the following Figure (Figure 3) shows. Populism is no longer a marginalised trend, but is coming increasingly into the mainstream.

Figure 3 The global rise of populism

Source: Rodrik, D. (2018), Populism and the economics of globalisation.

We can identify two major root causes of populism in Europe. First of all, it may be attributed to the failure of globalisation to reach some segments of the population, which have been left behind in terms of its economic benefits, for instance in Europe through chronic unemployment. Secondly, increased migration flows which triggered immigration fears and a stronger anti-euro sentiment and broader support for populist forces.

In Italy, the eurozone’s third-largest economy, two anti-establishment parties, the 5 Star Movement and the Northern League, which won 55% of the popular vote at the March general election, defeating the country’s traditional centrist political parties, have struck a deal to form an all-populist government with an anti-European sentiment. We should not take this prospect lightly, as Italy can be seen as a miniature representation of the whole of Europe.

Another disguised version of populism taking advantage of the Brexit prospect can be seen in the promise for broad-scale renationalisation, so-called Corbynomics, which would mean a return to the 1970s, by the British main opposition party leader, who has announced his intention to return to the model of nationalisation of banks, water industries, transport, etc., through the back door. Based on the pretext of market failures identified in their privatisation, full government control of such industries would be disastrous for the UK economy and the world, with a ‘megatone’ effect: 10 times bigger than Brexit.

Despite all this, a majority of EU citizens harbour a favourable opinion of EU membership, which has recovered to levels close to those recorded prior to the crisis. 57% of respondents to the European Parliament’s Parlemeter survey feel that the EU membership is a good thing for their country, almost as many as before the crisis (see Figure 4 below).

Figure 4 Public opinion on EU membership

Source: European Parliament, “Parlemeter 2017 – A stronger voice. Citizens’ views on Parliament and the EU”, p. 17.

In view of the upcoming European Parliament elections in June 2019, there are heightened fears of a further surge in populism in the form of protest votes, amidst the ongoing migration crisis. As the clock ticks down to the critical June European Council, European leaders must rise up to the challenge of introducing brave reforms and give to the people more reasons to trust the European Union as an endeavour and especially its institutions, because ultimately what the people want is jobs, growth and stability.

3. The candidate countries for euro area membership and the benefits from EU membership

3.1 The candidate countries

Following the accession of Lithuania on 1 January 2015, the process of euro area enlargement has stalled and none of the 8 EU non-euro area Member States (see Figure 5 above) has so far actively pushed EMU accession. Out of the two Member States, whose national currencies are linked to the euro, Bulgaria has stated its intent to join the interim Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM2) and Denmark has opted out of euro area accession.

Figure 5 Euro area and non-euro area member countries

Source: European Commission, COM (2017) 821 final, “Further steps towards completing Europe’s Economic and Monetary Union: a roadmap”, p. 2.

We do not expect any proposal for eventual euro area membership to be made in the ECB’s new Convergence Report, due to be published tomorrow (23 May), despite the progress made with regard to compliance with the five economic indicators, well-known as the “Maastricht criteria”, designed to ensure nominal economic convergence between interested non-euro area countries with the Member States of the euro area (see Table 3 below).

Table 3 Maastricht convergence criteria

Source: European Commission.

The ECB publishes convergence reports every two years, or when there is a specific request from a Member State to assess its readiness to join the euro area. The new Convergence Report should point out that none of the countries under review, that is, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Croatia, Poland, Romania and Sweden (given that Denmark has an “opt-out”), is under an excessive deficit procedure and point out that progress has been made in addressing imbalances in their economies and further improvements of their fiscal positions.

As you are aware, crucial to the ECB’s Convergence Report is the notion of “sustainable convergence”, which is not automatic upon fulfillment of nominal convergence criteria prior to the adoption of the euro, but also requires policy efforts and appropriate national reforms following the entry into the euro area.

President Juncker said in his State of the Union speech on 14 September 2017 that: “Member States that want to join the euro must be able to do so.” This is why he proposed the creation of “a Euro-Accession Instrument, offering technical and even financial assistance”.

As shown in the following table, some of the CEE countries outperform the euro area average, for instance on the government budget deficit or general government debt thresholds of 3% and 60% respectively (see Tables 4 and 5 below).

Table 4

Table 5 Government finance indicators for non-euro area EU CEE Member States, EU-28 and euro area

|

Country

|

General government net lending/borrowing (as a % of GDP)

|

General government gross debt (as a % of GDP)

|

|

|

2017

|

2018

|

2017

|

2018

|

|

Bulgaria

|

0.9

|

-1

|

23.9

|

23.6

|

|

Croatia

|

0.6

|

-0.5

|

78.4

|

75.5

|

|

Czech Republic

|

1.3

|

1.1

|

34.7

|

32.9

|

|

Hungary

|

-2

|

-2.1

|

69.9

|

67.4

|

|

Poland

|

-1.7

|

-1.9

|

51.4

|

50.8

|

|

Romania

|

-2.8

|

-3.6

|

36.9

|

37.8

|

|

EU-28

|

-1.1

|

-0.8

|

83.2

|

81.1

|

|

Euro area

|

-0.9

|

-0.6

|

91.3

|

84.2

|

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook (April 2018).

3.2 The benefits of EU membership for CEE countries

3.2.1 EU as a soft power

The benefits of EU membership should be clear by now to governments and citizens of CEE countries: considerable economic progress as part of the European Single Market, the gradual convergence of living standards with those in other European Member States, and of course progress towards modernity, including the move towards a market economy, the opening up of the labour market, free movement and free trade, a business-friendly environment and undistorted competition, etc.

There is no doubt that we are all part of the big European family. Unlike some autocratic leaders (no names please) who want to be lonely riders in an era of globalisation and also want to rule their central bank and make decisions on interest rates: just look at what has happened with the Turkish lira last week.

The European Union is a soft power and a community of values that has become a strong regional pole promoting shared prosperity, democracy, independent institutions, the rule of law and transparency across the European continent. Following the CEE countries’ EU accession, reform efforts have had to be sustained, as the EU has the potential to act as an external constraint by imposing common rules on its Member States and discipline on profligate politicians, through the transposition of the European acquis (for instance, combatting corruption).

3.2.2 EU financing to CEE Member States

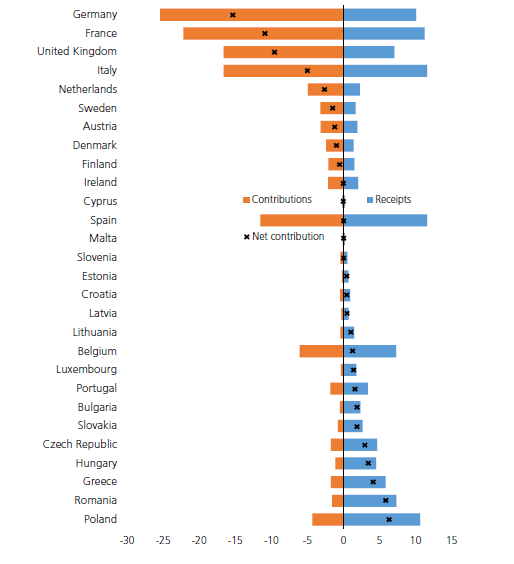

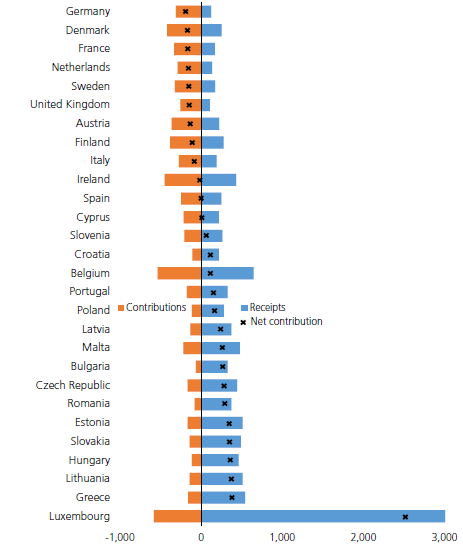

CEE Member States have been net recipients from the EU budget, as shown in Figure 6, and also in per capita terms, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 6 Net contributions to the EU budget by Member State (2016, in billion euro)

Source: European Commission, EU expenditure and revenue 2014-2020.

Figure 7 Per capita net contributions to EU budget by Member State (2016, in euro)

Sources: European Commission, EU expenditure and revenue 2014-2020, and Eurostat.

After EU accession and entry into the Single Market of 500 million consumers, the region has been recording rapidly improving economic growth rates offering an attractive environment for foreign investment, stronger demand, easy financing conditions and of course making the most of available EU funding, mainly through the EU’s structural and cohesion funds.

Under the current EU budget (formally known as the Multiannual Financial Framework or MFF) for the period 2014-2020, the 6 CEE EU Member States (that are not members of the euro area) are allocated €157 billion or 45.4% of the total amount earmarked for the EU’s two structural funds (European Regional Development Fund - ERDF and the European Social Fund - ESF), and the Cohesion Fund. Among 6 CEE Member States, Poland is by far the largest recipient of EU structural and cohesion funds (22% of total allocations), followed by Romania (6.4% of total allocations). By way of comparison, Greece has been allocated €15.8 billion, which represent 4.6% of total allocations. The CEE economies enjoy around 4% of GDP gross inflows from the cohesion and CAP funds on average during the current 2014-2020 EU budget cycle.

Table 6 EU funds allocated to CEE Member States and Greece under the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) 2014-2020

|

Country

|

In €

|

As % of total allocations

|

|

Greece

|

15,774,066,781

|

4.6

|

|

Bulgaria

|

7,312,413,787

|

2.1

|

|

Croatia

|

8,245,993,253

|

2.4

|

|

Czech Republic

|

21,501,038,980

|

6.2

|

|

Hungary

|

21,444,582,271

|

6.2

|

|

Poland

|

76,345,205,832

|

22.0

|

|

Romania

|

22,283,994,996

|

6.4

|

|

Total

|

346,289,772,498

|

100

|

|

Note 1: The figures refer to the two structural funds, namely the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and the European Social Fund (ESF), as well as the Cohesion Fund (CF).

|

|

Note 2: EU funds allocated to other countries are estimated at about €160 billion.

|

|

Source: European Commission.

|

This may fall by 0.2-0.7% of GDP during the next seven-year period. Under the new MFF 2021-2027, for which the European Commission presented its proposal to the Council of Ministers on 14 May. The total budget is worth €1.28 trillion and amounts to 1.11% of EU gross national income, which is about 1/50th of most EU Member State government spending. The aim is for the new budget to be approved by spring 2019, but the proposal has several contentious parts and difficult and long-drawn negotiations are expected between the Member States especially given the large budget gap to be left by the UK’s exit from the EU which may be addressed through additional funding from the EU-27, on which there is already strong opposition.

3.2.3 Current status on Romania’s prospective accession into the euro area

Romania has repeatedly pushed back its target dates for euro area accession from 2014 to 2015, then to 2019 and now to 2022. Between 2009 and 2013, the country had been subject to an excessive deficit procedure. Romania is currently experiencing an economic boom, with real GDP recording a post-crisis peak growth rate of 6.9% in 2017. This growth rate was driven by a boom in private consumption boosted by an expansionary fiscal policy and is expected to remain robust in the current year. According to the ECB’s previous Convergence Report, Romania now also meets the convergence criterion of price stability, which it did not fulfil according to earlier reports, along with the criteria on public debt and government deficit. So far, no decision has been made for the Romanian leu to enter the ERM2.

I am not here to advise when would be the right time to enter the euro area. Any decision to adopt the single currency is up to the people and their democratic institutions. But I would like to give you a word of caution concerning the conversion rate between your currency and the euro and my remarks apply to all candidate countries for euro area membership, not only to Romania. This conversion rate is the key to euro area accession and, once fixed, it is irrevocable for each participating currency. With the benefit of hindsight, I could share with you the Greek euro area accession experience, where it is debatable even today if the entry to the euro back in 2001 was made on the valid conversion rate (overvalued); also many people claim that the country needed more time to put its economy in order. Ex post, this is evident by the country’s economic devastation triggered by the global financial crisis back in 2008, which turned into a full-blown double crisis, namely sovereign and banking crisis, in my country.

In the case of Romania, things are quite simple. You don’t have to look at EU forecasts or Convergence Reports to find out. All you have to do is listen to the wise man that you are very lucky to have in this country: ask your Central Bank Governor Mugur Isarescu who, as you are aware, is widely regarded as one of a handful top central bankers in the world!

4. Post-MoU Greece

Finally, a few words about my country: Greece’s economic recovery is finally gaining traction after an unprecedented depression, where the country lost 25% of GDP in the space of 10 years. Real GDP in 2017 increased by 1.4% with strong positive contributions from exports of goods and services (2 percentage points) and gross fixed capital formation (1.2 percentage points). This positive outcome creates a strong carry-over effect of 0.5 percentage point for GDP growth in the current year, which supports the outlook for a growth rate of around 2% and 2.5% in 2018 and 2019 respectively.

Indeed, this is a fortunate moment for Greece. After 9 years of economic hardship, we can say with confidence that there is light at the end of the tunnel for the Greek economy. The economy’s progress during the last eight years of adjustment has been really impressive, both in terms of fiscal and external adjustment of more than 15 percentage points of GDP. The huge twin deficits turned into surpluses. Last year, the primary surplus was 4.2% of GDP, outperforming the target of 0.5%. The current account during the last two years had effectively been in balance, from a 15% deficit eight years ago. And last year: an all-time record of 30 million tourists visited the country.

Throughout this period, sweeping structural reforms have been implemented, covering the pensions system, the health system, labour markets, product markets, the business environment, public administration, etc. Moreover, there is evidence that the economy has been undergoing a rebalancing towards the tradable, export-oriented sector: the share of exports of goods and services in GDP increased from 19% in 2009 to 28% in 2016, with most of the increase coming from exports of goods.

Two weeks ago the results of the Greek banks’ 2018 stress tests conducted by the ECB were published, pointing to no capital shortfalls. Of course, despite the positive outcome of the stress tests, the major challenges are still there: for instance the drastic reduction of the non-performing loans and the ability to provide liquidity to the Greek real economy (new loans to businesses).

In view of the end of the current programme in August 2018 and a return to European normality, the Greek people look into the future with optimism, which I also share, provided that there is no complacency, no slackening of effort, and authorities do not let up on reforms, especially in the public sector, cutting red tape, etc.

The overwhelming majority in Greece still want to be within the core of Europe. This is our legacy as a nation that goes back to our history and our tradition. After all, the name of our continent Europe comes, in the first place, from an ancient Greek mythological figure, a beautiful young lady with whom Zeus, the father of the twelve Greek Gods, fell in love, but since she was refusing his advances, he decided to transform himself into a bull to catch her and bring her to Mount Olympus, the mountain of Gods in northern Greece, where I come from!

Concluding remarks

In closing, I understand that public sentiment in Central and Eastern European countries is not very strong right now in favour of joining the single currency and that euro area accession is seen by some as a byword for the loss of sovereignty. The crisis has certainly made the euro area look less attractive for future members. In my view, the issue is ultimately, on the one hand, for the eurozone to persist with completing the EMU project and, on the other hand, for candidate countries to be at a par with the rest of the eurozone on all fronts (sustainable convergence). After all, CEE Member States have considerable discretion over the timing of their accession into the euro area. Amid the uncertainty about the euro area’s architecture, a wait-and-see approach for final outcomes is perhaps the safe-bet policy, given that any decision to adopt the single currency, once made, is irreversible, since the costs of exit by far outweigh the benefits.

Thank you very much for your attention.

[*] Disclaimer: Views expressed in this speech are personal views and do not necessarily reflect those of the institutions I am affiliated with.