Speech by Bank of Greece Deputy Governor John (Iannis) Mourmouras at the 33rd Meeting of Central Bank Governors’ Club of Central Asia, Black Sea Region and Balkan Countries (Shanghai, China): “Low Inflation in the Euro Area: Symptom or Cause?”

15/05/2015 - Speeches

Governors,

Dear colleagues,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

It is a great pleasure for me to be here in Shanghai and I would like to thank the Governor of the People’s Bank of China, Mr. Zhou Xiaochuan, for inviting me to this high-profile meeting attended by esteemed colleagues of the central banking sector. I would like to share my thoughts with you on the problem of low and persistent inflation (and the appropriate policy responses) in the euro area, which numbers 19 Member States sharing a single currency, the euro.

I. INTRODUCTION

As you all know, the 2008 global crisis – mainly a crisis of credit and confidence expressed in both bond and equity world markets – turned into a sovereign debt crisis in the euro area in 2010, heightening market concerns about the sustainability of public finances of governments in the so-called europeriphery. That, in turn, hampered the expectations of the private sector, gave rise to prolonged fiscal consolidation, contributed to an anaemic recovery, to problems with the smooth transmission of the single monetary policy and thereby the achievement of the price stability objective. Over the course of this period, the ECB naturally took action against the fragmentation of the financial system in the area and took measures against a severe bank credit squeeze and a deep economic recession by introducing a very accommodative monetary policy stance which resulted in its latest decision: the quantitative easing (QE) implementation, which is essentially my topic today.

My remarks will focus on four areas. First of all, I will begin with a brief discussion of the recent inflation developments and prospects in the euro area. Secondly, I will briefly describe the QE practices of major central banks and, more precisely, those implemented by the Fed, the Bank of England and the Bank of Japan. Thirdly, I will discuss the ECB’s recent policy responses focusing in particular on its expanded asset purchase programme (QE). As you know, QE is rather a controversial idea. It has lots of critics. Opinions diverge across the board, from “one of the most radical monetary policy experiments of modern times” to “quasi fiscal policy”. And of course QE’s efficacy in Europe is of global significance, if only one takes into account the euro area’s big share in world output – not to mention the reactions of other central banks (e.g. in Switzerland, Denmark, Sweden, etc.). Last but not least, I will look into the challenges and risks that lie ahead for the overall stance of economic policy in Europe.

II. LOW INFLATION OR DEFLATION?

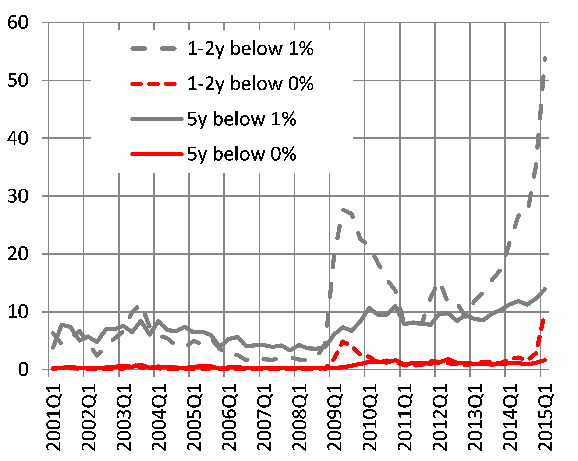

Before starting to unfold these issues, please allow me to explain why it is that we talk about low inflation, rather than deflation, in the euro area. In February 2013, euro area inflation fell below the 2% mark and has since been on a continuous downward trend for more than two years. According to the latest report of the ECB survey of professional forecasters (SPF), low inflation is expected to be quite prolonged, but gradually rise to 2%. According to Eurostat’s flash estimate, euro area annual HICP inflation was zero last month, -0.1% in March, up from -0.3% in February 2015 and -0.6% in January 2015, despite the fact that both measures of money supply, the broad M3 and the narrow M1 have been picking up this year (by 4.5% and 9.5% year-on-year respectively in the first quarter of 2015). Inflation is expected to remain very low or slightly negative in the coming months, with an annual inflation projection of 0.1% on average for the year 2015, against a yearly average of 0.4% in 2014. It is also true that in advanced economies, the inflation rate will stand at 0.4% on a yearly basis in 2015, according to the latest IMF forecasts, which is the lowest level in the last 30 years. However, inflation rates are projected to rise consistently over the short- and medium-term and reach 1.5% by next year. Although in the euro area, there is more than a 50% risk of the inflation rate hovering below one percent in the short-run, the risk of deflation is quite low at less than 10 percent in the short term (in the next one to two years) and effectively zero (1% risk) in the longer term (in the next five years), as shown in Chart 1. Ultimately, the ECB’s mandate is expected to be achieved, as the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) is expected to reach 1.8% in 2017, namely its primary goal of price stability, i.e. maintaining the euro area inflation rate below, but close to, 2% over the medium term.

Chart 1. Risks of low inflation vs. deflation (percentages)

Source: ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters and ECB calculations.

Notes: The latest observation is for the first quarter of 2015. Probabilities for the 1-2Y horizon are an average of the probabilities for the 1Y and 2Y horizons.

The main factors for the relatively small probability of deflation in the euro area are three: the ongoing economic recovery, the effects of the euro’s depreciation and the fact that monetary policy plays a supporting role. In addition, we do not generally expect negative energy price developments to impact wage developments significantly. In a classic deflationary cycle, households and firms defer expenditures when monetary policy is at the effective lower bound and the central bank cannot steer the nominal rate down to compensate for lower expenditure. This does not seem to be the case in the euro area. It is worth pointing out that core inflation – that is, the inflation rate that strips out energy and unprocessed food prices – remains low, but is still on the positive side with the latest reading for March 2015 at 0.6%. Consequently, using the term “deflation” for the euro area would arguably be an overstatement, with the ECB not expecting the euro area to fall into deflation.

However, the risks of low inflation appear to be linked to the risks of subdued growth or weak recovery (see also below). Quarter-on-quarter real GDP growth in the euro area was 0.3% in the last quarter of 2014, year-on-year change in 2014 was 0.9%, while the ECB’s March prediction for this year was at 1.5%. Euro area growth rates are still a full percentage lower than in the decade leading up to the crisis (2.5%), and are uneven across countries. It is true that domestic demand in the euro area has not yet reached its pre-2008 crisis levels. Particularly, business investment remained around 15% below its pre-crisis levels, which led to a sharp decline in the investment-to-GDP ratio. On top of that, the growth in government expenditure during the last five years was just 0.18%, against 1.8% in the period before the crisis.

What is perhaps a more worrying feature is the fact that the euro area stands out among large economies for the depth and likely duration of its bout of low inflation. Particularly, the ECB staff macroeconomic projections in March this year show a downward revision by 0.8 percentage point to the inflation forecast for this year and a slight revision by 0.2 percentage point to the inflation forecast for 2016, compared with the December 2014 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections. Inflation is now projected to be 0.1% in 2015 and 1.5% in 2016. The annual rate of change in core inflation has been consistently below 1% over the past year, with the latest reading for March 2015 at 0.6%, their lowest levels since the start of the series in 1997. A low reading for core inflation for such a prolonged period of time indicates that it is not only temporary factors that are at work: underlying demand weakness also plays a significant role, as well as of course contained wage pressures and structural reforms undertaken during the same period. Empirical evidence from the Phillips curve suggest that the negative output gap will last until 2019, which is projected by the IMF to stand at -2.3% in the euro area this year. Falling energy prices and slowing annual growth rates of wages and salaries in the euro area obviously contribute to persistently low inflation. All in all, the inflation problem in the euro area is quite challenging. Low inflation is already hurting debtors in the euro area since their incomes are rising more slowly than what they expected when they borrowed.

III. OTHER CENTRAL BANKS’ QE PROGRAMMES

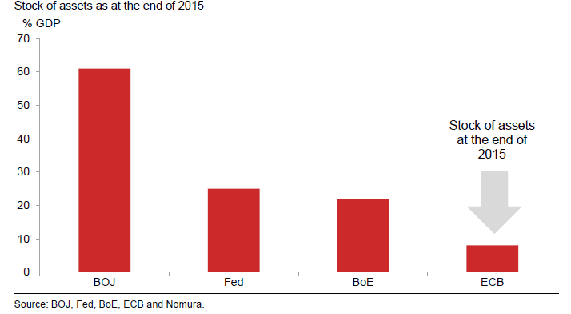

Allow me now to briefly review the programmes of large-scale asset purchases (LSAPs) implemented so far by the other major central banks, focusing mainly on their impact on the real economy. Fed used its balance sheet – with purchases of public and private assets – to provide stimulus to the economy amidst the credit crunch of 2008. To give you the whole picture of the size of the Fed’s balance sheet over the past several years: assets have risen from about 900 billion US dollars in 2006 to about 4.5 trillion US dollars today, accounting for 25 percent of nominal GDP from 6 percent of nominal GDP in 2006 (CHART 2).

Chart 2. Stock of assets purchased by central banks as a percentage of national GDP

The net expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet over this period primarily reflects these large-scale asset purchase programmes. But how effective was the Fed’s policy? After nearly 6 years of large-scale asset purchases, a substantial body of empirical work on their impact has emerged. According to the Fed’s own research, the large-scale purchases have significantly lowered long-term Treasury yields, which translated into reduced corporate bond and mortgage security yields. But was this ultra-expansionary monetary policy effective for the overall economy’s performance in the US? Model simulations conducted at the Federal Reserve generally found that the securities purchase programmes have provided significant help to the US economy. For instance, a study using the Federal Reserve Board’s model (FRB/US) of the economy found that, as of 2012, the first two rounds of LSAPs may have raised the level of output by almost 3 percent and increased private payroll employment by more than 2 million jobs, relative to what otherwise would be the case. In conclusion, as Stanley Fischer, the Fed’s Vice Chair, noted in his speech last February that QE programmes coupled with increasingly explicit forward guidance have reduced the unemployment rate by 1-1.25 percentage points and increased the inflation rate by half a percentage point, relative to what would have occurred in the absence of these policies.

A similar policy was conducted by the Bank of England in response to the intensification of the financial crisis in the autumn of 2008. The aim of the policy was to inject money into the British economy in order to boost nominal spending and thus help achieve the Bank of England’s 2% inflation target. According to the reported estimates of the peak impact, the £200 billion QE programme implemented between March 2009 and January 2010 is likely to have raised the level of real GDP by 1.5% to 2% relative to what might otherwise have happened, and also to have increased annual CPI inflation by 0.75 to 1.5 percentage points. The Bank of England’s own conclusion is that the effects of its QE programme have been “economically significant”.

Last but not least, the Bank of Japan’s large-scale asset purchases were primarily aimed at boosting money supply, asset prices and inflation expectations, while holding down interest rates. As regards asset prices as a result of the QE programme, stock prices are up and the yen/dollar exchange rate has fallen. But what about the Bank of Japan’s 2% inflation target? For the period leading up to the 2008 financial crisis, inflation expectations appeared modestly positive and rose significantly above their historical average. This suggests that the BOJ’s 2% inflation target might be gaining credibility. Lately, the Bank of Japan decided to expand its quantitative programme in order to act in an orderly manner against weak developments in demand. Whether this decision will eventually help the rate of inflation reach 2% remains to be seen.

IV. THE MAIN FEATURES OF THE ECB’S QE

Turning now to the euro area, the question is how exactly has the ECB acted and is still continuing to act? More specifically, what has been the ECB’s immediate response to achieve its primary goal of price stability? Let me quickly present the ECB’s monetary policy stance over the last eight years, which saw the euro area faced with particularly adverse circumstances:

• The main refinancing rate was gradually cut to just over zero (0.05%) and the deposit facility below zero, to -0.20%, its lowest level since the launch of the euro;

• The ECB’s second line of action was a policy of forward guidance and a more active use of its balance sheet;

• All eligible financial institutions have unlimited access to central bank liquidity at the main refinancing rate, as always subject to adequate collateral with extended maturity of liquidity provision. A programme to provide targeted long-term funding (TLTROs) to banks is also implemented;

• As part of special programmes, private sector securities such as covered bonds are purchased by both the ECB and the euro area’s National Central Banks (CBPP - Covered Bond Purchase Programmes 1 & 2) and asset-backed securities only by the ECB (ABSPP);

• The asset purchase programme was expanded to include sovereign bonds, under the public sector purchase programme (PSPP), commonly known as QE, which entered into effect on 9 March 2015. In this context, let me remind you that in 2010 the ECB started purchasing securities under the Securities Markets Programme (SMP, outstanding amount €138 billion from a maximum amount of €220 billion), and in 2012 initiated the outright monetary transactions (OMT) in secondary sovereign bond markets in order to address the severe tensions in certain market segments and safeguard an appropriate monetary policy transmission. After the ECB President’s pledge “to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro” in the period following the OMT announcement, tensions in sovereign bond markets subsided, with Spanish and Italian ten-year government bond yields to fall significantly. In essence, the ECB reaffirmed its full commitment to our price stability mandate, sending a strong message to financial markets. Let me briefly explain the main objective and the key characteristics of the ECB’s expanded bond-buying toolkit. The explicit objective of the ECB’s programme is “a sustained adjustment in the path of inflation that is consistent with its aim of achieving inflation rates below, but close to, 2% over the medium term”.

The key elements of the programme are the following:

1. Combined monthly asset purchases will amount to €60 billion of private and sovereign debt;

2. In total, the programme will amount to €1.1 trillion in asset purchases carried out from March 2015 until September 2016, but the programme may be extended if its objectives are not achieved.

3. Loss-sharing is reserved for those purchases that are carried out by the ECB or fall on securities issued by supranational European institutions, amounting in total to 20%. The remaining 80% of all purchases – falling on purchases made by NCBs – will not be subject to loss-sharing. This mix corresponds approximately to the current allocation of fiscal responsibilities in the euro area, thereby preserving needed fiscal discipline incentives for euro area governments.

4. The spectrum of securities covered by the QE includes: (i) nominal and inflation-linked central government bonds, and (ii) bonds issued by recognised agencies, international organisations and multilateral development banks, provided the issuers are located in the euro area. Of these, only securities with a residual maturity ranging from two (2) to thirty (30) years will be eligible. In terms of issuer breakdown, the ECB intends to allocate 88% of the total purchases under the PSPP to government bonds and recognised agencies and 12% to securities issued by international organisations and multilateral development banks.

5. Also, in order to ensure proper market formation, two limits are applied in terms of issues and issuers, calculated in nominal values. On the one hand, the ECB won’t buy more than 25% of each issue. The 25% issue share limit is applied in order to avoid a blocking minority in the event of a debt restructuring involving collective action clauses (CACs). On the other hand, the ECB won’t buy more than 33% of each issuer’s debt. The 33% issuer limit applies to the combined holdings of bonds bought under all of the ECB’s purchase programmes and to the universe of eligible assets in the 2 to 30-year range of residual maturity. It is a means to safeguard market functioning and price formation, as well as to mitigate the risk of the ECB becoming a dominant creditor of euro area governments.

One last remark on the modalities of the programme. The ECB buys public sector bonds on the secondary market, refraining from asset purchases on the primary market in order to remain compliant with the Lisbon Treaty’s provisions on the prohibition of monetary financing (Article 123). An obvious question that might arise then is the following: Is there really any economic distinction between buying government debt in the secondary market from buying it directly from the government (i.e. monetising public debt)? The answer is a clear cut “yes” and the crucial point is that the central bank is not being forced to create money in order to cover the gap between the government’s tax income and its spending commitments.

V. THE MAIN CHANNELS

But how will the expanded asset purchase programme work in terms of boosting inflation, restoring economic growth, employment in the euro area and contributing to the attainment of the ECB’s objective? There are a number of potential key channels through which asset purchases may affect spending, inflation, and borrowing costs to the real economy.

• First of all, a portfolio rebalancing channel can be identified where investors are likely to redistribute their portfolios by substituting lower risk assets with riskier assets such as longer-term assets, equities and possibly real estate. Bidding up the prices of assets bought leads to lower yields and lower borrowing costs for firms and households, thus stimulating spending. In addition, higher asset prices stimulate spending by increasing the net wealth of asset holders. Consequently, an improvement in net wealth, combined with a general improvement in economic prospects and hence future earnings, can expand the capacity of firms and households to borrow. This is an important channel in every single QE programme adopted so far, with its effect as a primary channel of transmission of monetary policy programmes centred on outright purchases.

• Another important channel is the signalling effect whereby the central bank’s balance sheet expansion signals a turn towards an accommodative monetary policy stance over an extended horizon and pushes back the date on which a policy rate hike is expected. By introducing a QE programme, a central bank can send a strong signal that it will continue to be able to loosen monetary policy and stimulate demand even when monetary policy rates hit a lower bound, which could have had a strong impact on private sector’s inflation expectations and thereby lower real interest rates, boosting economic activity and inflation.

• The third channel is of course the exchange rate which is not an objective in itself, but it reflects the market participants’ expectations of the ECB’s very accommodative monetary policy. The nominal exchange rate of the euro has already fallen by 11% since last December, while the programme’s expanded and open-ended nature will maintain the currency at its current low levels.

• All these factors are short-term and this is consistent with traditional policies of central banks which are geared towards the short/medium term. However, QE by its very nature is an extension of the intervention horizon of monetary policy and as such it can create favourable conditions for long-term investment and hence boost the potential growth of the euro area. For instance, the weighted average remaining maturity of the securities purchased as part of ECB’s QE is currently 8.5 years (on 6 May 2015). So monetary policy in the euro area is having a more direct impact on long-term interest rates than ever before.

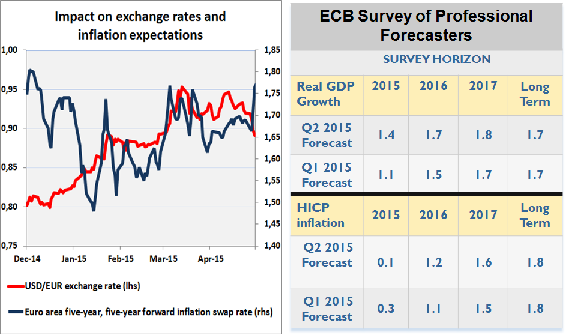

VI. THE ECB’S QE: AN EARLY ASSESSMENT

A number of analysts have already discounted the limited efficacy of QE in the euro area on the grounds that banks rather than capital markets dominate the provision of credit there. They claim that, for instance, US companies raise much of their funding in the bond markets and the main channel through which QE has boosted the US economy is by lowering corporate borrowing costs. This effect would clearly be much weaker in the euro area. Having said that, and although is still very early days, preliminary evidence (soft evidence if you like) on the impact of QE is really encouraging. The latest economic data and, particularly, survey evidence available up to March point to improvements in economic activity since the beginning of this year. The so-called indicators (industrial production, construction production, capital goods production, retail trade and car registrations) all signal a further rise in euro area activity and output in the first quarter of 2015. Moreover, compared with the December 2014 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections, the projections for real GDP growth in 2015 and 2016 have been revised upwards (Chart 3a), reflecting the favourable impact of significantly lower oil prices, the weaker effective exchange rate of the euro and the impact of the ECB’s asset purchase programme. Furthermore, credit dynamics also gradually improved. According to the latest data, the annual growth rate of total credit in the euro area increased to 0.4% in March, from 0.0% in the previous month. Among the components of credit to the private sector, the annual growth rate of loans increased to 0.1% in March, from -0.1% in the previous month. Loan growth in the euro area averaged 5.41% from 1992 to 2015 with a record low of -2.30% in November 2013 and shows the first positive signs for the first time since January 2014. All this shows an improvement in the credit channel, confirming a further recovery in loan growth. According to the April 2015 ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, annual real GDP will rise by 1.5% in 2015, 1.9% in 2016 and 2.1% in 2017. Furthermore, model-based estimates indicate that market-based measures of inflation expectations have reacted positively to the progressive expansion of our balance sheet over the last few months and have been revised upwards, as well (CHART 3a). Although euro area HICP inflation is at the same level as in 2009, the current level of inflation expectations is well above the historical low reached in 2009. Break-even inflation rates – derived from five-year German government bonds – have overcome the lows recorded in early January (below zero) and currently stand at 0.85%. Having increased steadily since mid-February, they suggest that the decline of expectations was largely driven by temporary factors and that concerns about deflationary pressures have abated recently. This trend is confirmed by the evolution of inflation-linked swaps for a wide range of maturities, from which a euro area inflation curve can be drawn. Market-based short-term inflation expectations have recovered from the troughs they reached in January. For the short term, inflation-linked swap rates at the one year-forward one-year-ahead horizon stood at 0.9%. Swap rates at the three-year-forward-three year-ahead horizon would imply an average inflation rate of 1.5% (taken at face value). On a longer horizon, the widely watched five-year forward five-year-ahead indicator recovered strongly from its low point in January and at the time of writing suggests an inflation of 1.7%, a level which minimises concerns about a possible de-anchoring of inflation expectations. Having fluctuated around its long-term average of 2.3% for most of 2013, the five-year forward five-year ahead implied rate declined in 2014. Currently it is hovering around 1.7 %, slightly lower than the ECB’s SPF (2015Q1) results.

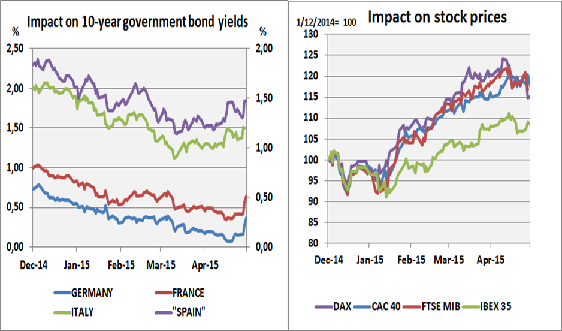

As far as financial markets are concerned, the impact of the asset purchase programme accounts for most of the fall in euro area long-term sovereign bond yields since last December, as market participants anticipated the ECB’s QE programme. Government bonds across a wide range of euro area countries traded at historically low and often negative yields. The decline was most pronounced in the longest maturities, with yields on French and German 10-year bonds falling by around 60 basis points, while those on Italian and Portuguese bonds of the same maturity shrank by 70 and 90 basis points, respectively. Yields on corporate euro-denominated debt have also gone done while the major European stock markets have risen from the end of 2014 by 17% approximately (CHART 3b). [Note: Charts 3a and 3b do not capture the recent bond sell-off in early May, which was in my view a market reaction to an overshooting of euro area sovereign bond prices following the QE’s formal announcement by the ECB in January of this year.]

Chart 3a. The ECB’s QE: Impact on the Macroeconomy

Chart 3b. The ECB’s QE: Impact on Financial Markets

A case in point is that from just before the announcement of the ECB’s expanded asset purchase programme on 22 January to the close of business the day after, German 20-year maturity yields fell by almost 25 basis points and Italian 20-year maturity yields fell by almost 35 basis points. Furthermore, as we mentioned earlier, the euro depreciated by 11% since last December, hitting a 12-year low against the dollar (CHART 3a).

On the other hand, the effectiveness of the ECB’s QE programme in terms of contributing to a robust recovery in the euro area should have a significant final impact on the global economy and indeed in this part of the world. Such an accommodative policy that aims to raise ultimately consumer confidence in the euro area, obviously stimulates imports from the rest of the world. An illustration of this is that total EU trade with Asia reached €1.03 trillion last year, almost double the value recorded a decade ago and, at the same time, the EU accounted for 22,4% of Asian trade in 2014, with most of EU imports coming from China (6.7% of total EU imports). The EU is also a major investor in the Asian continent. Only last March the European Commission announced over €6.5 billion in new support for countries and organisations in Asia for the period 2015-2020.

VII. FINAL REMARKS

From the above analysis, there is a rather straightforward answer to the question posed in the title of my speech, if the euro area’s low inflation is a symptom or a cause of weak recovery: the current low inflation environment is rather a symptom than a cause of weak demand. The latter is the key effect of deflation on the real economy due to the deferment of private spending. The important question is of course if the policy proves effective at the end, what – and how certain – would be the final impact of QE on aggregate output and on anchoring inflation expectations. Moreover, if the monetary stimulus is not sufficient to achieve the policy objective, what role fiscal policy could play alongside monetary policy. I turn to these issues right now, and these will be my closing remarks.

Verdict on QE

To start with the first question the truth is that we cannot identify precisely how much of an impact on the economy is a direct result of QE or something else. Moreover, we will probably never know exactly the degree of efficacy of QE for the simple reason that we can never know with precision what would have happened in its absence. On top of that, we are living in an era full of uncertainties; the only certainty is that there is no certainty! Often our decisions are only as good as our last meeting. However, even if QE’s other effects are uncertain, I expect the signalling effect and the resultant boost in confidence to be quite strong.

What more should be done

If the euro area’s low inflation persists and recovery remains weak, then priority should be given to complementary fiscal policy, such as changes into the composition of government spending towards bringing forward public investment, especially if one considers the fact that long-term borrowing rates are so low today. Such a policy would boost aggregate demand in the short run, but also it would aim to improve productivity (TFP, the main driver of long-run growth, is moving at negative rates since 2007 in the euro area). In this context, the European Commission’s investment plan for Europe (also known as the Juncker plan) comprising a package of measures to unlock public and private investments in the real economy of at least €315 billion over the next three years (2015-2017) is undoubtedly in the right direction. This is quite presumably what President Draghi had in mind when he made the following remarks last August, speaking in another famous gathering of central bankers in Jackson Hole in Kansas: “It would be helpful for the overall stance of economic policy if fiscal policy could play a greater role alongside monetary policy, and I believe there is scope for this […]”.

Of course, neither QE nor public investment should be seen as an alibi in postponing crucial, growth-enhancing structural changes, like for instance reforms to improve the functioning of product and labour markets, to reduce red tape and increase the efficiency of public administration, etc. As a matter of fact, given that Europe today faces a twin recovery and growth challenge (namely the quest for a robust recovery in the short run through demand stimulus measures and for a sustainable growth path in the long run through supply side reforms) we need to use all three policies jointly, and at the same time.