Speech by Bank of Greece Deputy Governor John (Iannis) Mourmouras at Cass Business School “First HBA-HAA Lecture” in London entitled: “Recent monetary and economic developments in Greece”

23/03/2016 - Speeches

Ladies and Gentlemen,

It is a great pleasure to be here. I would like to thank both associations, the Hellenic Academics Association and the Hellenic Bankers’ Association, for inviting me to speak to you today at the familiar premises of Cass Business School. Although I was in London only last January for a speech on European monetary policy at the Houses of Parliament, the newly-elected Chairman of HBA, Antonis Ntatzopoulos, managed to persuade me to come again so soon. Thank you also, Antoni, for your kind welcoming address. I am delighted to see in the audience many of my former students from my time as University Professor here in London, now as members of London’s banking and academic community.

My lecture will be structured in two parts. The first part investigates the ECB’s recent monetary decisions and their impact on inflation dynamics, also exploring the benefits and limits of such policies. In the second part, I will offer some reflections on the current economic situation in Greece, its outlook and short- to medium-term prospects.

A. The ECB’s unconventional monetary policy

1. The ECB measures announced on 10 March 2016

A brief look, now, at the ECB measures announced on 10 March 2016. Ten days ago, the ECB Governing Council decided in favour of a more accommodative monetary policy as follows:

- The interest rate on the main refinancing operations of the Eurosystem has been cut by 5 basis points to 0.00%, the interest rate on the marginal lending facility has been lowered by 5 basis points to 0.25%, and the interest rate on the deposit facility decreased by 10 basis points to -0.40%.

- The monthly purchases under the asset purchase programme will be expanded to €80 billion per month starting in April, from €60 billion per month currently, taking the total size of the asset purchase programme to €1,740 billion by March 2017.

- Investment grade euro-denominated bonds issued by non-bank corporations established in the euro area have been included in the list of assets that are eligible for regular purchases (as of 11.03.2016, the ECB has purchased under the APP programme: €801.2 billion: PSPP Holdings: €620.5 billion, ABSPP Holdings: €19.1 billion, CBPP3: €161.6 billion. Breakdown: €46 billion on the primary and €115.6 billion on the secondary market.)

- A new series of four targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO II), each with a maturity of four years, will be launched in June 2016.

My short comment on the above measures is that they are a combination of quantitative easing with credit easing, namely a widening of QE as seen from the higher amount of monthly purchases, and credit easing as evident in the eligibility of corporate debt for ECB purchases, plus of course the second round of TLTROs, meaning literally that the central bank pays commercial banks to provide loans to businesses.

Why did ECB President Mario Draghi decide to proceed even further with the above expansionary monetary policy, eleven months after the initiation of the program?

2. The current economic outlook of the euro area

The answer to the above question lies in the euro area economic outlook.

- Core inflation fell to 0.8% in February (flash estimate), down from 1.0% in January. According to ECB forecasts in March 2016, inflation in the euro area is now projected to be at a very low level (0.1%) on an annual average basis in 2016, before rebounding to 1.3% in 2017 and 1.6% in 2018.

- Inflation expectations, as measured by the five-year inflation-linked swap rate, declined to a historic low of 1.37%, compared with 1.7% just prior to the start of the PSPP.

- GDP growth has been revised downwards by 0.4 percentage point, to 1.4% for 2016; for 2017 and 2018, real GDP is expected to grow by 1.7% (revised downwards by 0.1 percentage point) and 1.8%, respectively.

In short, it seems that up to this point the QE programme had a rather minimal impact on inflation or inflation expectations and growth in the eurozone.

From my point of view, three main factors have contributed to the inability of inflation to increase.

(1) First, supply-side factors have been deflationary, as reflected in a decline in the price of oil (as measured in US dollars) of about 25% since early March. Evidence of a sustained rise in underlying inflation has yet to be seen, while falling industrial producer prices also signal weak inflation dynamics.

(2) Second, demand-side factors, as reflected in the persistence of the euro-area’s negative output gap, continue to exert downward pressures on prices.

(3) Third, under the Phillips curve relationship, inflation expectations are a main determinant of the present inflation. Consequently, to generate increases in present inflation, it is necessary to increase inflation expectations. However, inflation expectations have been declining since the initiation of the PSPP.

3. Some positive evidence from QE

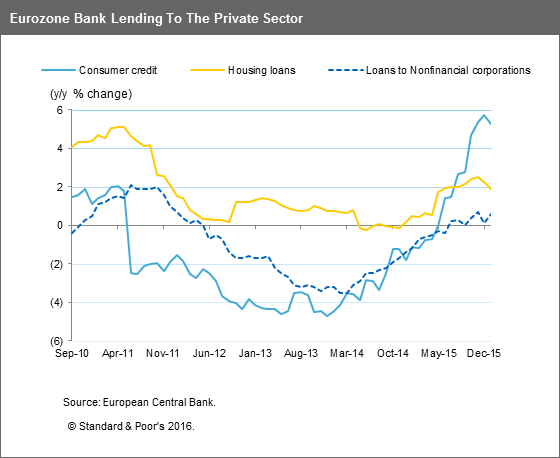

It is true that there is some encouraging evidence mainly from the M3 growth and the banking sector, such as the growth rate of loans.

- M3 growth accelerated to 5.0% in January, compared with a 4.7% rise in December (M1 growth was 10.5% in January, compared with 10.8% in December).

- The annual growth rate of loans to non-financial corporations increased to 0.6% in January, compared with 0.1% in December.

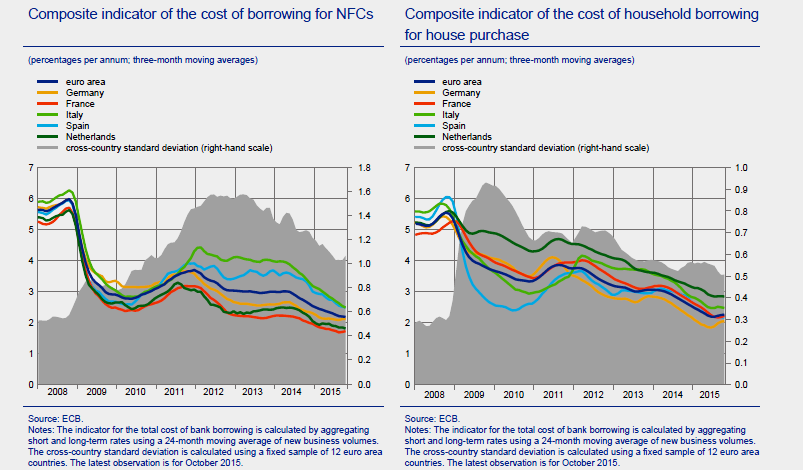

- The verdict so far is that QE has reduced fragmentation in the eurozone financial markets. More specifically, bank lending rates decreased, with significant declines recorded in the nominal cost of bank borrowing for non-financial corporations (NFCs) and households (by 79 and 65 basis points respectively, see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Euro area lending to the private sector

Figure 2. Composite indicators of the nominal cost of bank borrowing for households (for house purchase) and non-financial corporations in the euro area

Source: European Central Bank

- Cross-country heterogeneity in bank lending rates has declined further. For example, since last summer the average cost of borrowing for euro area non-financial corporations has fallen by around 70 basis points, and by 90 basis points and 110 basis points for NFCs in Spain and Italy, respectively.

- Since the start of the QE programme in March the euro depreciated against the dollar by 2%, while since the beginning of the year it has depreciated by about 10%.

- The purchase programmes have also greatly contributed to a significant decline in sovereign yields, a compression of intra-euro area spreads and a flattening of yield curves across all markets that were only partially offset by the bond market correction that began in early May. More precisely, Germany’s benchmark 10-year Bund is trading at 0.26%, while currently more than eleven two-year government bonds of euro area Member States are trading with negative returns (compared with 8% for Greece).

B. Recent economic developments in Greece

Let me now move on to Greece. After six years of austerity and reforms, the country is again at a crossroads and under heightened uncertainty as a result of the delay in the completion of the First Review of the 3rd MoU, the setbacks in the implementation of structural reforms and privatisations, and finally due to the mounting migrant crisis.

B1. The state of the economy

Coming now to the prospects of the Greek economy, I will try to make three quite important remarks, but before that I will give you a few figures on the Greek economy.

Economic activity

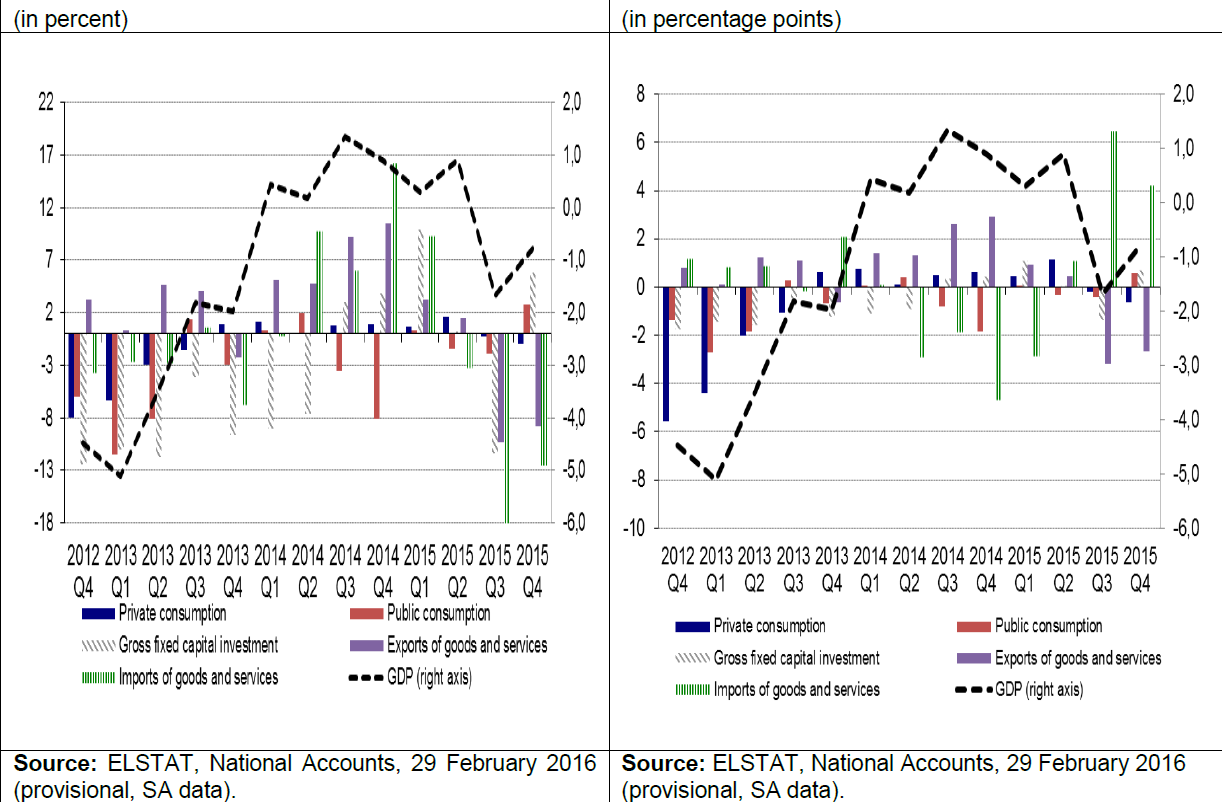

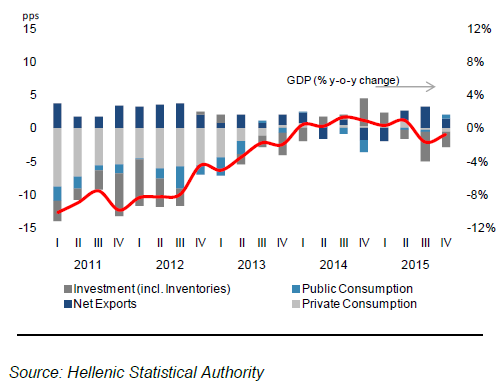

Although European Commission initial forecasts suggested that Greece’s economic activity would be severely affected (-4% in 2015), the final data suggest that recession in 2015 was milder than initially expected, i.e. -0.2% for the whole year.

Figure 3. Average annual GDP growth rates and main components

Due to the carry-over effect from the second half of last year, the Bank of Greece’s estimate for the growth rate in Q1 and Q2 this year is negative, turning to positive in the second half of the year.

Money, inflation and credit

- Inflation has been negative over the past three years (2013-2015) and stood at -1.1% on average in 2015 (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Inflation

(percentages)

.png)

Sources: ELSTAT and Bank of Greece calculations.

- The completion of bank recapitalisation in December 2015 is a step towards the restoration of confidence in the Greek banking system that will facilitate the gradual recovery of bank deposits.

Figure 5. Monthly flows of deposits from non-financial corporations and households

(in billion euro) .png)

Source: Bank of Greece.

- In January 2016, the rate of contraction of bank credit to non-financial corporations, which has been deteriorating since July 2015, speeded up to an annual rate of -1.6%. The respective rate of bank credit to households decelerated slightly to -3.0% (see Figures 6 and 7).

Figure 6. Bank credit to households

(in billion euro; annual percentage changes) .png)

Source: Bank of Greece.

Figure 7. Bank credit to non-financial corporations

(in billion euro; annual percentage changes)

.png)

Source: Bank of Greece.

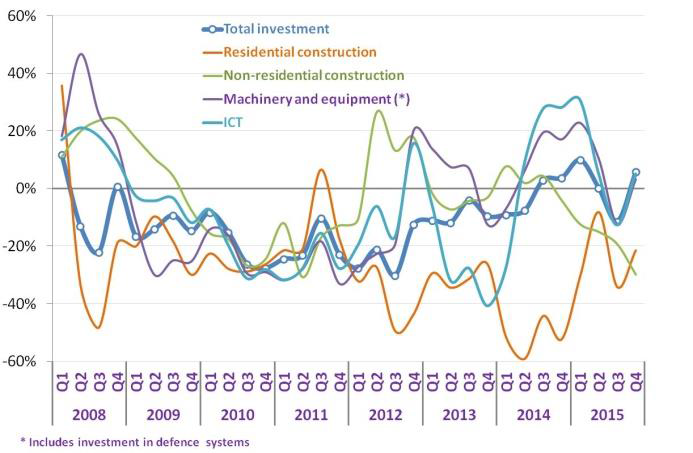

Disinvestment: the long-term risk

The most important upside risk to the growth outlook is related to the generalised disinvestment situation that Greece faces for a prolonged period. For example, in 2007, investment was 27% of GDP, whereas last year it was 12% of GDP, the lowest level since 1960, and, taking into account depreciation, we have effectively had negative net investment for all the previous years. No physical capital accumulation, the debasement of human capital due to the brain drain and lack of spending on skills, all these point to hysteresis effects on long-term growth in Greece.

Figure 8. Investment growth

Source: ELSTAT.

Figure 9. Investment in the EU-28, US and Greece

(as a percentage of GDP)

.png)

Source: AMECO 2014.

For 2016, European Commission forecasts that disinvestment in Greece will continue, albeit at a slower rate (-3.7%), before increasing in 2017, as shown in the following Table (Table 1).

Table 1. EU Economic Forecasts

(winter 2016)

.png)

Source: European Commission.

Figure 10. Greece’s GDP components

Figure 11. Investment by asset

(as a percentage of GDP)

.png)

Figure 12. Greece’s disinvestment evolution

(in million euro)

.png)

Source: ELSTAT.

B2. Three remarks

I will now turn to my three remarks.

First remark:

Since 2010, I have been writing and speaking about this. Out of all the problems that the Greek economy is faced with, i.e. unemployment, recession, public debt, private debt, non-performing loans, disinflation, etc., I would definitely place, in terms of importance, recession/lack of growth at the top, and not public debt, especially after the PSI, which some view as the number 1 problem and even go as far as to ask for a nominal haircut in public debt, something which is ruled out by the European treaties. A return to normality will only be achieved through growth that will create jobs, bring social cohesion and increase wages and salaries across the Greek population. All this is achieved by means of steady positive growth rates, which will in turn improve public debt dynamics and sustainability, but will also reduce unemployment, effectively tackle non-performing loans and private debt, and so on. If I may slightly rephrase US President Bill Clinton: “It’s the growth, stupid!”

I have one further comment regarding private debt now, which exceeded €200 billion, and now accounts for 113% of Greece’s GDP. The breakdown is as follows: NPLs: €100 billion, tax arrears: €80 billion, overdue insurance contributions: €20 billion. Given its short- to medium-term effect on private consumption (which determines GDP growth by 75%), doubts arise about the growth prospects of the Greek economy in the next five to ten years. Given the disinvestment issue, which I discussed earlier, that is why I have been writing since 2010 that the country badly needs an investment shock.

Second remark:

Nobody, I am sure, in this room, but also outside of it, would wish for the unpleasant experience of last year’s backtracking to be repeated this year, i.e. the deposit outflow which destabilised the banking system and resulted in the introduction of capital controls, a bank holiday and bank recapitalization – only a year following the 2014 recapitalisation – and, of course, the recession in 2015 and 2016, from initially positive expectations for both years.

The cost of last year’s backtracking was elevated, as we all understand, but what I would like to point out here today is that the cost of any further delays this year would be equally high. If the negotiations of the first review of the 3rd Memorandum are drawn out over time, then the risks of a destabilisation of the economy and its financing conditions would be heightened.

Let me be more precise: I should mention that the cost of this delay is reflected in the deferment of voting major bills at the Hellenic Parliament which are at a stalemate for some time now, although they concern critical issues relating to the country’s growth, such as the development law, the new framework on public procurements, the modernisation of public construction works, scientific research and development. Without a timely review, all of the above bills are in the air. The price to pay for our economy will be heavy.

I hope that the benefits of a timely review are clear to everyone. And for one more reason: the credibility deficit vis-à-vis both the markets and our creditors as a result of last year’s delays (2 elections in just 9 months, a referendum, the country coming to the verge of Grexit) which led to the signing of the 3rd Memorandum, can only be overcome, at this point, with deeds and tangible proof that agreements are kept in Greece: i.e. that fiscal adjustment measures and reforms are implemented, and privatisations are accelerated. Pacta sunt servanda, as the Latins say.

Third remark:

A question I am often asked in Athens, as you might suspect, is whether I am optimistic about the country’s economic prospects. Mark Twain said something along the lines: The man who is a pessimist before 50 knows too much; he is wise man; if he is an optimist after 50, he simply needs to visit a GP! So my answer to those who asked me whether I am optimistic is that if there is a timely conclusion of the first review, I see the glass half-full for the following reasons: in the short-term, immediately, confidence will be drastically restored, thus accelerating a return of deposits to the Greek banking system and this will, in turn, lead to a further relaxing of capital controls and, once again immediately, lead to Greek government bonds being readmitted as eligible collateral for Eurosystem operations, under the so-called ‘waiver’. Such a development will allow the provision of much cheaper financing for Greek banks by the ECB, hence boosting liquidity provided to the real sector of the economy.

Furthermore, the successful conclusion of the First Review will be immediately followed by a start in negotiations with our creditors for public debt relief, and improvements in credit ratings for Greek government bonds and, in the end, our participation in the quantitative easing programme of the ECB, something which will become a catalyst for the drastic reduction in Greece’s borrowing costs, a return to international capital markets and finally a return to European normality for my country.

Thank you very much for your attention.

*Disclaimer: Views expressed in this speech are personal views and do not necessarily reflect those of the Bank of Greece.