Keynote speech by Bank of Greece Deputy Governor John (Iannis) Mourmouras entitled: “Recent developments in tackling the Greek non-performing loans problem” at the 2nd Annual Investors’ Conference on Greek & Cypriot NPLs

13/02/2019 - Speeches

1. Introduction

Good morning, Ladies and Gentlemen,

It is my pleasure to deliver the keynote speech at the second Annual Investors’ Conference on Greek and Cypriot NPLs, a very welcome initiative that draws the attention of all the relevant stakeholders on the NPL issue, of great interest to the local regulator too, which justifies my presence here in front of you. I would like to start by thanking the organisers, the Information Management Network and Jade Friedensohn, for the kind invitation, and all of you for being here so early in the morning.

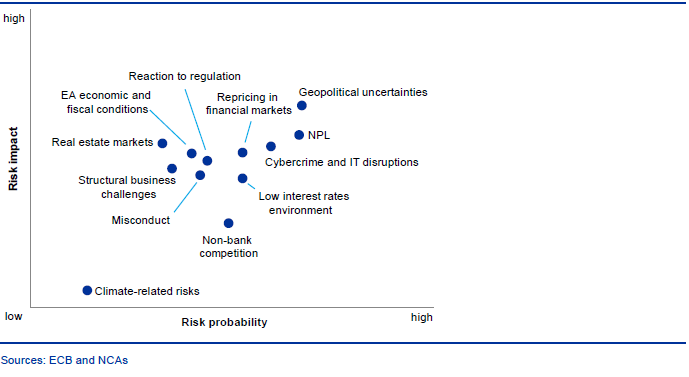

Because of the criticality and the multidimensional aspects of the issue and a sense of urgency, some have called it the Achilles’ heel of the Greek banking system; others the elephant in the room. I personally call it a problem, a problem that can be resolved and I see that the time has come. Over the last decade, the European Union and its Member States have worked hard to reduce risk in the banking sector. Indeed, the European banks average CET1 ratios are 15%, the highest level since 2014, while according to the latest ECB’s stress tests results published last Monday, all banks improved capital basis with higher capital buffers than in 2016. Despite that, according to the recent SSM risk map for 2019, NPLs continue to pose risks to economic growth and financial stability with further efforts necessary to ensure that the NPL issue in the euro area is adequately addressed, while the ongoing search for yield, due to very low and negative interest rates, increases the potential for a build-up of future NPLs (Chart 1).

Chart 1. SSM risk map for 2019

As you can see from the chart above, NPLs rank higher than cybercrime and IT disruptions, and are second only to geopolitical uncertainties both in terms of risk impact and risk probability.

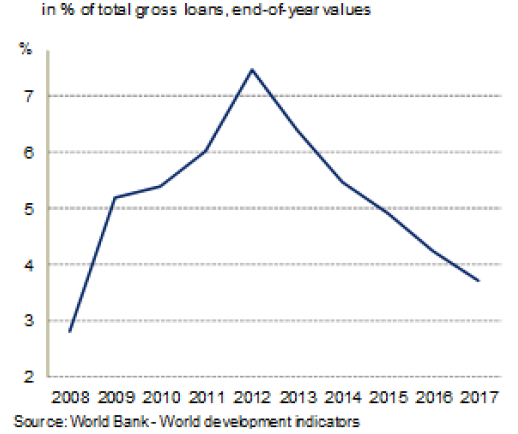

The average NPL ratio in the EU stands at 3.4% and this compares with average NPL ratios of 1.3% and 1.5% in the United States and Japan, respectively.

In what follows, I would like to highlight the European dimension to the NPL issue including the current situation of NPL secondary markets across the euro area, in other words, that NPLs is not only a Greek problem, but it is also a concern to other South European countries, including Cyprus, Italy, Portugal, etc. My focus will then be the recent developments in tackling the Greek non-performing loans problem including the two recent systemic proposals, one by us at the Bank and one by the HFSF.

2. NPLs: The broader context across the European banking sector

a. Recent developments

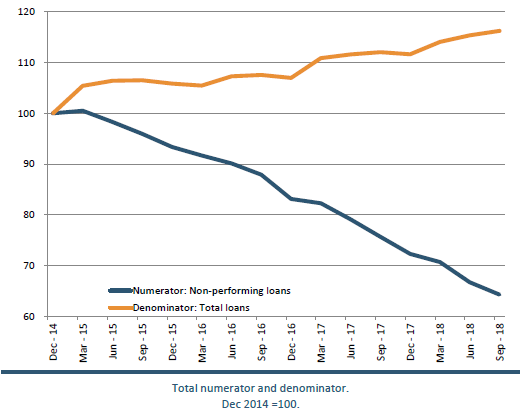

NPL ratios continued to decline last year across the European Union, confirming the overall trend of improvement over recent years. The latest figures show that the gross NPL ratio for all EU banks further declined to 3.4% (Q3 2018), to the lowest level since 2014, indicating that the NPL ratio is approaching pre-crisis levels again (Chart 2). The coverage ratio has also further improved and has risen to 46% (Q3 2018), up 3 percentage points since 2014.

Chart 2. EU bank total non-performing loans

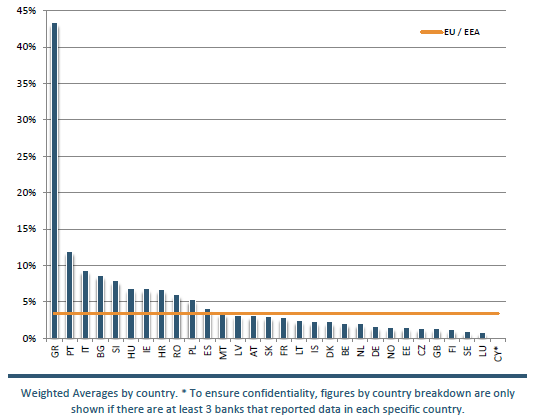

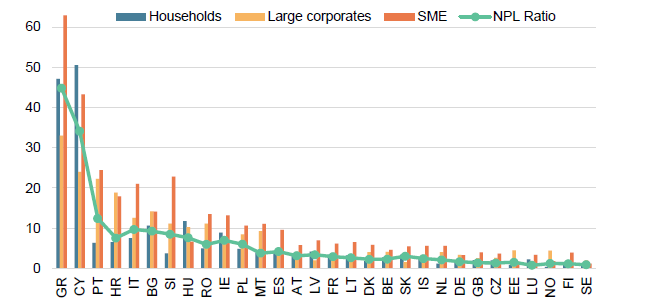

However, the situation continues to differ significantly between Member States as 12 EU Member States have NPL ratios of below 3%, while there are still some with considerably higher ratios – 9 Member States have ratios above 5% (Chart 3). in Member States with relatively high NPL ratios, there is encouraging and sustained progress in most cases due to a combination of policy actions and the growth impact. For instance, in Cyprus, NPLs have continued to fall since the end of 2015 with the NPL ratio around 34% and are expected to decline more sharply this year. In Italy, where the NPL ratio is currently around 9.7%, the securitisation scheme supported by state guarantees (known as GACS) was introduced in 2016 and extended for another six months in September 2018. Several other market infrastructure initiatives are also helpful towards tackling NPLs. For example, in Portugal that has an NPL ratio of 12.4%, initiatives targeted at promoting smooth coordination among creditors (to accelerate credit restructuring, NPL sales, etc.) are a welcome addition to the existing policy mix.

Chart 3. NPL ratios in EU Member States

In this context, last December, the European Council Presidency and the European Parliament agreed on a new framework for banks to deal with new NPLs and thus to reduce the risk of their accumulation in the future. The framework provides for requirements to set aside sufficient own resources when new loans become non-performing and creates appropriate incentives to address NPLs at an early stage. In particular, the new rules introduce a "prudential backstop", i.e. common minimum loss coverage for the amount of money banks need to set aside to cover losses caused by future loans that turn non-performing, which increases gradually over a period of 9 years. The full coverage of 100% for NPLs secured by movable and other CRR (Capital Requirements Regulation) eligible collateral will have to be built up after 7 years, while for the unsecured NPLs the maximum coverage requirement would apply fully after 3 years.

b. Current situation of NPL secondary markets in Europe

Let me now turn to the current situation of NPL secondary markets in Europe. These remain underdeveloped, given that:

1. Markets for NPLs tend to be characterised by comparatively small trade volumes. Indeed, between 2014 and 2017, transaction volumes in secondary markets for loans in the EU were estimated by industry sources to reach between €100-150 billion per annum.

2. The NPL market has been highly concentrated on the buy side with a few large transactions involving a limited number of active investors. The 10 largest transactions during the period 2015-2016 accounted for one third of the transaction volume, while the rest was spread over about 480 transactions. Moreover, almost 40% of the transaction deals was accounted for by the biggest five buyers, while about 70% of the market share in the EU is controlled by 20% of investors.

3. Transactions have been strongly clustered in four countries: Spain, Ireland, Italy and the United Kingdom. In the first three, NPL sales have contributed substantially to reducing high NPL ratios. There have been few transactions in other countries with high NPL ratios (Greece, Cyprus, Italy, Portugal, Slovenia) and sizeable market activity in countries with low NPL ratios (Germany, Netherlands).

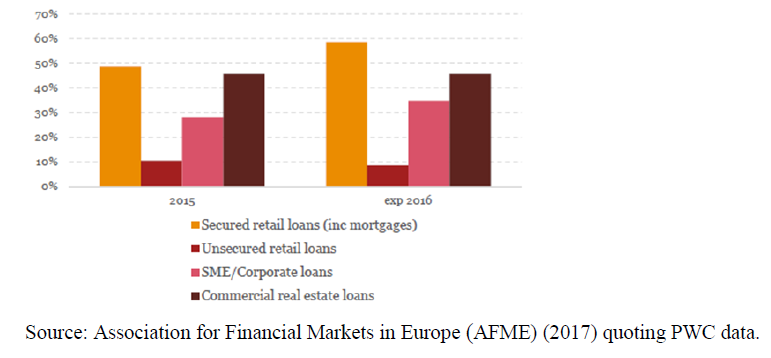

More precisely, of the 103 banks that disclosed transactions, only 40 had multiple transactions. The loan portfolios that banks sell include different asset classes and according to market sources, some buyers are specialised in specific asset classes. The chart below gives a snapshot of market shares by asset class based from a sample of 365 NPL transactions signed in 2015-2017 (Chart 4).

Chart 4. Loans and NPLs on bank balance sheets per asset class and country (June 2018)

4. There is lack of transparency of market prices and volumes with large bid-ask spreads when counterparts enter negotiations. Industry sources estimate that prices vary strongly depending on the type of debt and the quality of the underlying collateral (Chart 5).

Chart 5. Average price on face value of NPL portfolio transactions

An optimal and sustainable solution that has the potential to address the current sources of market failure in the secondary market for NPLs in Europe, including asymmetry of information between sellers and buyers and high transaction costs, is the establishment of a European Union-wide NPL transaction platform where holders of NPLs – banks and non-bank creditors – and interested investors can exchange information and trade, increasing competition, harmonising information and data availability. This could be turned into a permanent channel through which future NPLs could be efficiently disposed of.

3. A glance at the Greek economy

Before analyzing Greek banks’ NPL issue, allow me look into the recent developments on the Greek economy.

- For the first time in 10 years, economic activity returned with solid growth at 1.5% in 2017. Indeed, this is the first time Greece has achieved 6 consecutive quarters with positive GDP change since 2006. GDP growth is mainly export-driven, as improved external competitiveness combined with solid external demand has underpinned export growth. GDP growth is estimated at 2.1% and around 2% in 2018 and this year respectively.

- The unemployment rate declined further to 18.3% in the third quarter of 2018, remaining on a downward path, the lowest level since August 2011.

- On the fiscal front, the 2018 general government primary surplus target of 3.5% was outperformed by a strong margin (4%) and according to the 2019 budget, it is projected to reach 3.6% of GDP.

Looking forward, there should be no complacency or slackening of effort on behalf of the national authorities especially this year, a multiple election year in Greece. The government must commit to the implementation of growth-enhancing reforms and not lag behind its post-bailout commitments, particularly in the public sector, including administrative reforms and speeding up of judicial procedures. As I keep saying in the last eight years, on every opportunity I get, the country needs an investment shock. Reviving domestic and foreign investment is crucial to supporting the country’s economic recovery. This is why it is important for the government to speed up the privatisation agenda, not so much as a revenue exercise, but as a first-class opportunity to attract FDI in key sectors of the economy, such as transport, energy, logistics and tourism. All the above, will enhance the country’s credibility in the eyes of international capital markets and credit rating agencies, making the investment grade within reach.

Evidence on reduced sovereign risk

Last week, the Hellenic Republic raised €2.5 billion issuing a 5-year government bond at a yield of 3.6% and an annual fixed coupon for investors of 3.45%. This was Greece's first attempt to tap the international money markets after the country's exit from the third bailout programme last August. The issue was four times oversubscribed as offers, amounting to over €10 billion with the foreign investors’ participation exceeding 85%, with many real money investors and not only hedge funds. As the Greek government yield curve has been rebuilt, its slope has been steepened for the first time since 2015, implying improved investor perceptions about the outlook of the Greek economy.

In short, Greece is already in the markets with the only exception of the 10-year benchmark new issue. Since the start of the year the trading volume in the secondary securities market has been raised substantially from €5 million to €20 million on a daily average and the repo transaction volume has reached €22 billion from 0 three years ago.

As far as the benchmark is concerned, the 10-year GGB is currently trading at a yield of around 3.9%, i.e. near the March 2006 – the pre-crisis levels. Just to remind you that the 10-year GGB yield was 7.3% at the beginning of 2017. In my view, it is only a matter of time for a new 10-year government bond issue. Apart from its obvious importance for the Greek economy, it is also of direct interest to all of you, in terms of the pricing of future NPL securitisation products, since their guarantees are calculated on the basis of a basket of Greece’s sovereign CDS premium on the state guarantor.

4. Greek banking sector: Recent developments and their NPL issue

Turning now to Greek banking sector:

- For the first time since 2010, and after three rounds of capital injections in the last five years, amounting in total to €64 billion cumulatively, all four systemic banks successfully concluded the 2018 stress test conducted by the ECB, without any need for additional capital increases.

- In this context, according to their latest announced financial results for the third quarter of 2018, they remained in profitable territory with their capital ratios remaining at comfortable levels near 16% on average. However, the figures remain weak, as net interest income continues to decrease.

- Banks’ dependence on the ELA emergency lifeline has been terminated.

Another visible improvement in the financial sector was the increase of the total deposits between end-June 2015 and January 2019 by €20 bn (or 13%) to €150 bn.

- Greece’s four systemic banks’ covered bonds of 3 and 5-years maturity have been upgraded to BBB-.

- Last but not least, since last October capital controls on domestic transactions have been fully lifted. They are still in place though for money transfers abroad. Reminding ourselves that 2019 is a year of multiple elections in Greece, it goes without saying that there are downside risks by definition during electoral periods. I believe caution is the word here. Having said that, I would argue that it wouldn’t do any harm if the authorities preannounce the end-date for the full lifting of capital controls, say, by the end of this year, signaling that the country is on the steady path towards fully restoring confidence.

Greek banks’ NPLs: Where we stand now

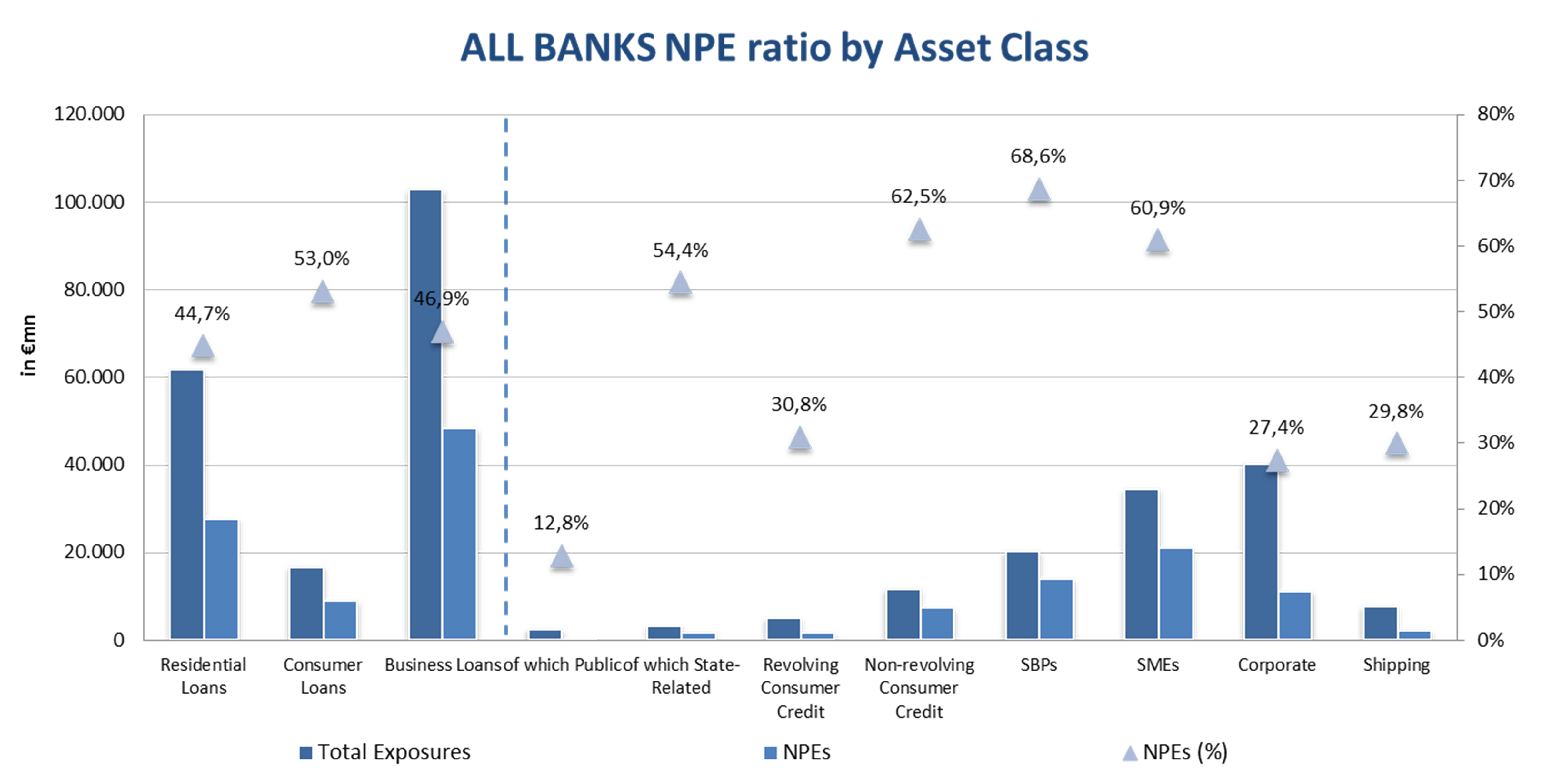

However, the most important pending issue for the Greek banking industry today remains the high stock of non-performing exposures, as Greece remains the outlier for NPEs with a ratio of 46.7% or €84.7 billion, the highest level across both the European Union and the eurozone.

Compared to March 2016, when the Greek banks’ stock of NPEs reached its peak, there is significant reduction of around 21% mainly due to write-offs and loan sales, which reached the amount of €17 billion.

More analytically, at end-September 2018, the NPE ratio was 44.7% for residential (amounting to €27.5 billion), 53% for consumer (€8.8 billion) and 46.9% (€48.2 billion) for the business portfolio (Chart 6). A major improvement has been made only on the consumer loans portfolio on the back of the latest sales. On the other hand, exceptionally high remain the NPE ratios in SMEs and SBPs (60.9% and 68.6% respectively).

Chart 6. Greek banks NPE ratio per asset class (%) as of end September 2018

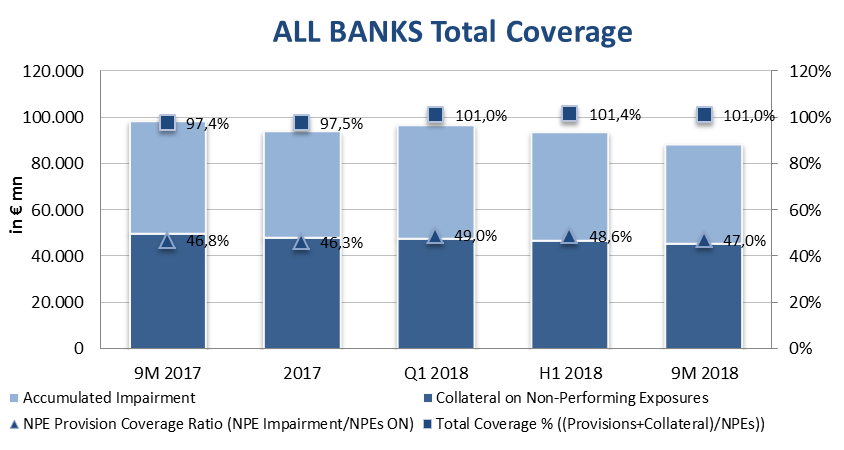

On the other hand, the NPE provisions coverage ratio has dropped at 47% from 49% previously (Chart 7).

Chart 7. Greek banks total coverage as of Q3 2018

Examining the reasons behind this substantial surge in NPEs in Greece, this can be attributed to three factors:

a. First of all, the severity of recession that wiped out 25% of GDP in just five years and the subsequent rise in unemployment from around 8% in 2008 to 28% in 2013.

b. Bad bank practices. Imprudent lending with high leverage and dubious practices of lending on undeclared income, and high LTV ratios.

c. Overborrowing by consumers and businesses following the introduction of the euro currency due to the sharp drop in interest rates.

Greek banks have already submitted revised operational targets for NPLs at ratios around or lower than 20% of total non-performing exposures by the end of 2021. Loan sales, collections, collateral liquidation and potential asset protection schemes are anticipated to contribute more extensively towards NPE reduction.

In this context, Bank of Greece (BoG) has designed a toolkit for the Greek NPLs including the following:

- Setup of a secondary market for NPLs. Seventeen AMCs have already received licenses, while another 11 companies are in the queue for a license, either by submitting a file or by preparing it.

- Out-of-court settlements law ffocused on standardized procedures for SMEs and electronic auctions.

- The Bank of Greece issued a Code of Conduct for interaction of banks with borrowers in arrears.

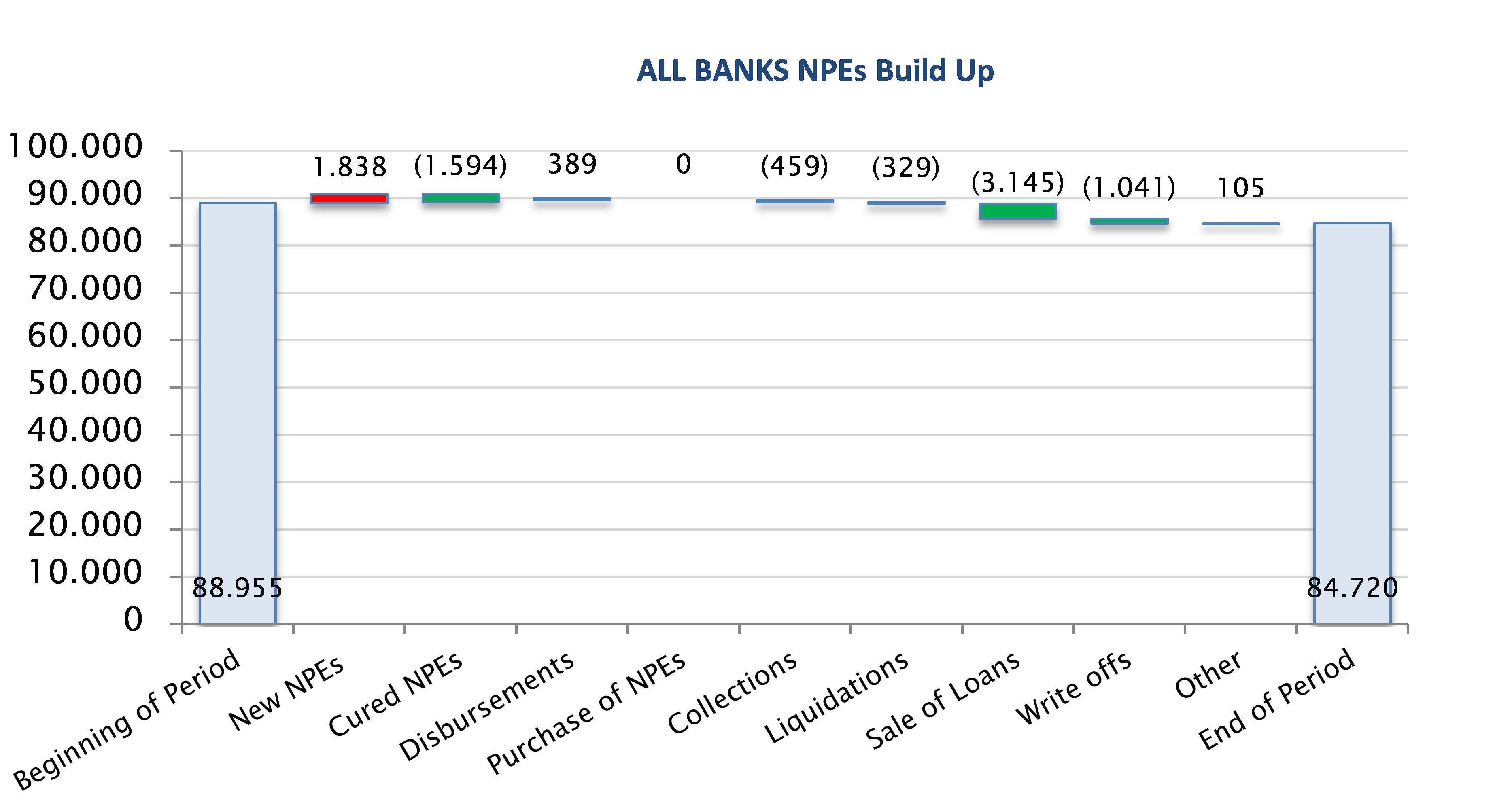

However, all banks have net NPE inflows for the third quarter of 2018, of around €1.8 billion mostly coming from re-defaults (Chart 8). Also, the quarterly cure rate remains near 1.8% and the default rate is 2.1%, thus further demonstrating the negative performance already observed in the first two quarters of 2018.

Chart 8. Flow of NPEs in Q3 2018 at system level

Hence, despite the genuine effort on the part of Greek commercial banks, more drastic solutions are needed in the foreseeable future with a hands-on approach. The speed up of efforts by both Greek banks and authorities is more than essential for a rapid convergence of the domestic NPL ratio to the European average.

Looking at the various strategies put forward for the effective resolution of the Greek NPL issue, from my point of view, securitisation schemes are probably the silver bullet for the Greek NPL problem. It’s an attractive, market-friendly idea because it converts bad quality assets to marketable securities, which could be of interest to a larger set of buyers, including foreign institutional buyers. The advantage of securitization is that there is significant diversification of risk away from a single credit name, and with the issue of tranches, investors can choose the risk-reward combination that best reflects their preferences. Securitisation also generally achieves a lower average cost of funding and, if guarantees are provided to the securitised assets, can result in higher NPL prices than direct sales.

Recently, two proposals are under discussion in order to address the issue of NPLs, one by the Bank of Greece and the other by the HFSF, which have both as a common ground, the ideas of securitisation and a systemic approach to the problem. They could be seen as complements, rather than substitutes. More analytically:

The Bank of Greece’s proposal - Main characteristics

The proposed scheme envisages the transfer of a significant part of non performing exposures (NPEs) worth of around €40 billion along with part of the deferred tax credits (DTCs) worth of around €8 billion, which are booked on bank balance sheets, to a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV). Subsequently, legislation will be introduced enabling to turn the transferred deferred tax credit into an irrevocable claim of the SPV on the Greek State with a predetermined repayment schedule. To finance the transfer, the SPV will proceed with a securitisation issue, comprising three classes of notes (senior, mezzanine, and junior). It is anticipated that private investors will absorb part of the upper class of securities (senior) and the vast majority of the intermediate part (mezzanine). The scheme will be voluntary and will be managed exclusively by private investors (servicing companies for loans and credits) and apparently there will be an asset class separation for each transaction and management operation (business, housing, consumer, etc.).

Turning now to the HFSF’s proposal: main characteristics

It is based on the Italian solution, the so-called GACS scheme, introduced in the beginning of 2016, which was conceived to help the country’s banks offload their bad loans. At the heart of the GACS programme is a state guarantee that protects buyers of the safest - or most senior - tranche in the securitisation. The guarantee will be available only after a) the senior tranche gets a certain rating by rating agencies (possibly in the area of BB) and b) at least (50% +) of the junior tranche is sold to private investors. The scheme will be voluntary again. Each participating bank will sell selected, relatively homogeneous portfolios of NPLs to the SPV, which will issue the asset-backed security notes.

After all, guarantee certificates are not something new in Greece, but have been used extensively by the banking sector since 2012 for central banking liquidity provision purposes (e.g. MROs and ELA), the so-called GGGBBs, which amounted to around €30 billion. These guarantee certificates can be considered as a sort of credit enhancement device with the following advantages: they do not put any capital pressure upon banks, they do not mix complicated tax, legal and regulatory issues.

With all the above firepower initiatives put in place, plus the existing toolkit of liquidation, restructuring and outright sales, the new ambitious target lower than 20% NPE ratio for Greek banks within the next three years is within reach.

Epilogue

Ladies and Gentlemen,

In closing, I would say the following. Being a macroeconomist by training, I can see a macro dimension in a drastic solution of the NPEs problem: to me, this is a unique opportunity,

• Not only for restructuring business bad debt, but also rebalancing the Greek economy towards export-oriented sectors, while contributing to long-term growth.

• For reducing financial risks of the Greek banking sector, restoring their profitability and improving their internal capital generation capacity, and

• Increasing loan supply to healthy and productive enterprises and enabling banks to focus on the new technological challenges ahead, including fintech, blockchain and the digital transformation of payment systems.

Thank you very much for your attention. I wish you all a productive conference and networking!