Speech by Bank of Greece Deputy Governor John (Iannis) Mourmouras in New York: “Some Reflections on Greek and European Capital Markets”

07/10/2015 - Speeches

Some Reflections on Greek and European Capital Markets*

I am delighted to be in New York. Today, I would like to share my thoughts and exchange views with you on Greek and European capital markets in these particularly volatile times. First of all, I will talk about the third MoU in Greece, capital controls and the forthcoming bank recapitalisation and, secondly, I will offer some reflections on current developments and future prospects of Greek and European capital markets, looking into the main drivers behind them.

I. GREECE

1. Basic elements of the third MoU

The key characteristics of the third MoU

Following months of intense and rather overdue negotiations, the Greek authorities signed the third economic adjustment programme, worth €86 billion over the coming three years (2015-2018), out of which €54.1 billion will cover debt amortisation and interest payments (€37.5 billion in amortisation and €16.6 billion in interest payments), €25 billion will be disbursed to cover the upcoming bank recapitalisation and resolution costs and the remaining amount will be used for arrears clearance. The Hellenic Parliament ratified a set of upfront fiscal measures (a total package of around €8 billion), which are for the most part (80%) based on a fair balance between indirect taxation and pension cuts. The above fiscal measures adopted in the context of the third MoU are expected to offset the deviation of the 2015 fiscal outcome vis-à-vis the new primary balance targets of -0.25% of GDP in 2015, 0.5% in 2016, 1.75% in 2017, and 3.5% in 2018 and beyond.

In addition, Greece has to implement more reforms, inter alia, the Hellenic Statistical Authority’s full legal independence, reform of the Code of Civil Procedure, the transposition into Greek legislation of the EU’s Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive and the introduction of quasi-automatic spending cuts in case of deviations from the primary surplus target, as well as labour market reforms particularly regarding collective dismissals, industrial action and collective bargaining, and liberalisation of a series of product markets and of restricted professions such as solicitors, actuaries, bailiffs.

Finally, Greece has also committed to push forward the ongoing privatisation process and preserve private investor interest in key tenders. The privatisation agenda aims at annual proceeds (excluding bank shares) of €1.4 billion in 2015, €3.7 billion in 2016 and €1.3 billion in 2017.

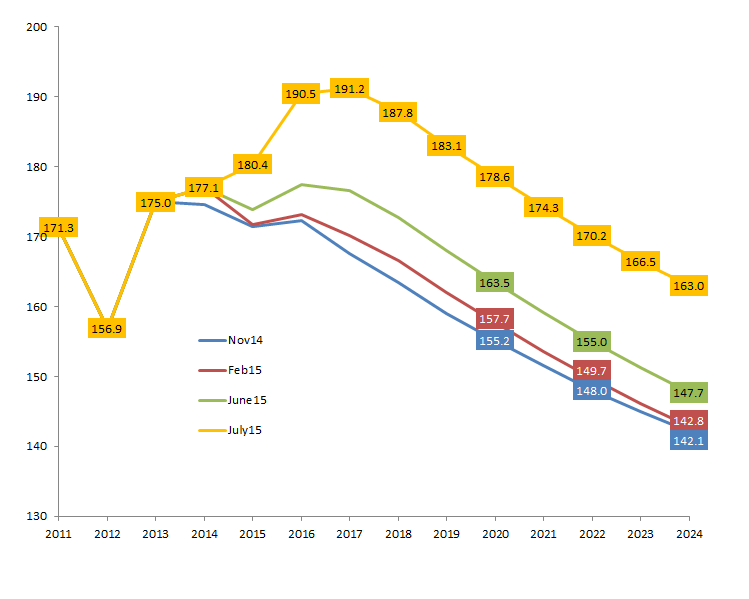

Debt relief

A very important pending issue is debt relief. The creditors will make their decisions after the successful completion of the current MoU’s first review, scheduled towards the end of the year. Currently, the outstanding total amount of the Greek general government debt is €312.8 billion (or 175.4% of GDP). According to IMF projections, the debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to reach 170% of GDP in 2022. In addition, Bank of Greece research suggests that since the imposition of capital controls Greece’s public debt increased further by 15.3% of GDP to 163% until 2024. In any event, the total debt service interest burden is 4% of GDP in the coming decade, about the same as that of Portugal.

Chart 1: Debt dynamics (2011-2024)

Source: Bank of Greece.

My guess - and this is only my guess - is that debt relief will move in one way or another along the lines of the November 2012 Eurogroup decisions (i.e. within the framework of ‘extend and pretend’).

2. Two preconditions for a third-time lucky (?) MoU

Greece now has a new and stable coalition government with a pro-European stance, committed to the euro project. However, for a successful and hopefully final MoU, leading to Greece’s return to international capital markets, a smooth political cycle at least in the medium term (three years) is what is now needed in Greece.

A. POLITICAL STABILITY

The imperfections of Greece’s political system (cronyism, short-termism, prone to recurrent elections, etc.) are long-standing and well-known. A credible and lasting way out of this state of affairs in order to protect the country’s economy against so many and frequent government changes is through constitutional reform, which at least in special and extraordinary times like the one we are experiencing over the past few years, should safeguard a more stable electoral cycle. The government’s term in office in Greece should be uninterrupted in order to have more time at its disposal to implement difficult but imperative policies. By way of indication, the presidential election, especially given that the President performs more ceremonial and official duties, should not be used as a pretext to push for early elections and cut short a government’s term in office (as was the case with the elections in January 2015, followed by a national referendum in July 2015).

Last month, Mr. Tsipras was emphatically re-elected as Greece’s Premier, the Syriza parliamentary group now consists of moderate MPs, the vast majority of opposition parties are also in support of European compromise, and also no other election (regional, local or European) is expected in the foreseeable future. All the above provide reassurance to our lenders and the markets that Greece will finally stick to its bailout commitments.

B. REMOVAL OF CAPITAL CONTROLS

The second precondition is lifting capital controls as soon as possible. Such a timely removal of capital controls goes through a successful bank recapitalisation, but could also be spurred by the reinstatement of the waiver affecting marketable debt instruments issued or fully guaranteed by the Hellenic Republic in order to reduce and finally put an end to the expensive emergency liquidity assistance (ELA) and thus enable Greece’s participation in the ECB’s quantitative easing programme (QE). I will now give you my insights on how, when and which steps can be taken on the above issues in order to effectively and quickly return to the international capital markets.

State of the economy after the imposition of capital controls

It should be pointed out that the decision for the imposition of capital controls in Greece was taken on the basis of financial stability considerations due to potential huge deposit outflows after the July 5 referendum on the bailout conditions set by Greece’s creditors.

Although initially European Commission forecasts suggested that Greece’s economic activity would be severely affected, real GDP growth increased in the second quarter of 2015 by 0.9% (1.6% on an annual basis). Preliminary data from the real sector suggest a negative impact of capital controls on the real economy and a sharp rise in uncertainty:

• GDP is expected to contract significantly in the second half of the year with Bank of Greece estimating the annual real GDP growth at between -0.8% and -1.3%.

• Economic confidence declined sharply in August (75.2 from 81.3 in July), almost reaching a historical low, mainly driven by a considerable decline in consumer confidence as a result of growing pessimism about the general economic situation and unemployment (over 27%).

• The stock of arrears (suppliers and tax refunds) increased to €5.7 billion, surpassing by almost €2.0 billion its December 2014 level.

• However, the worsening of GDP dynamics will be offset by tourist arrivals and receipts which are expected to reach record highs (+7% against 2014) and also the significant contraction of the trade deficit, as nominal goods imports fell by 32.0% (estimated at -25% in real terms) in July due to capital controls.

• Greek banks closed for three weeks under the legislative act of 28 June 2015 providing for a bank holiday of short duration. Trading in the Athens stock exchange ceased on 29 June. On its reopening after 5 weeks, it recorded a decline of 16.23%, with banking shares plunging by more than 20%.

• Bank credit contracted at an annual rate of around -3% in July 2015. The rate of contraction of bank credit to non-financial corporations deteriorated in July and reached -1.1%, reversing the gradual slowdown observed since February 2014.

• The level of non-performing loans (NPLs) is likely to increase from the current 47%, as capital controls further erode the ability and willingness of borrowers to repay their loans.

Bank recapitalisation

We are now facing a fourth round of recapitalisation to be carried out for the first time under the newly adopted Bank Resolution and Recovery Directive (BRRD). It is now imperative to recapitalise the Greek banks by the end of this year in order to avoid use of the BRRD’s bail-in tool, which will enter into force on 1 January 2016. The BRRD will be implemented under the precautionary recapitalisation tool or under the government financial stabilisation tool (GFST Articles 56-58 on extraordinary public support) depending on whether the private sector’s participation will be sufficient or not to cover the capital needs of Greek banks, as determined by the ECB’s comprehensive assessment. In both cases, the recapitalisation framework will be aimed at preserving the private nature of the recapitalised banks and facilitating private sector involvement. Of course, no effort should be spared on all sides to avoid unnecessary dilution of existing investors’ equity. The equities of the capital increase as part of the second round of recapitalisation worth of €8.3 billion and covered only by private investors, have been diluted by 88%, but also equities of the Hellenic Financial Stability Fund (HFSF) have been diluted. Note also that all four systemic banks have a CET1 capital ratio well above the minimum requirement with an average CET1 capital ratio close to 12% (based on data reported at end-June 2015).

In addition, it is envisaged that any remaining capital requirements under the adverse scenarios of the ECB’s stress tests will be covered by the HFSF. There is an ongoing debate on whether the HFSF will participate through the issuance of common shares or through the issuance of contingent convertible securities (‘CoCos’) in order to avoid a dilution of shareholders’ equity in case of recapitalisation under a highly stressed scenario. What such a CoCo instrument would look like is under discussion, but it would have to meet all the relevant criteria to be a CET1 equity-equivalent (if and when the Common Equity Tier 1 ratio falls below 8%, then CoCos will be converted into common shares).

In short, there are three major pending issues as regards the planned recapitalisation of Greek banks:

1. The level and treatment of non-performing loans (NPLs), which are the “Achilles heel” of the Greek banking system, as pointed out by the IMF. The impaired loan ratios for the banks’ Greek loan portfolios averaged 45% at end-June, while coverage of impaired loans in Greece averaged 50%. As a matter of fact, the last seven years, loan provisions have increased fivefold from €8 billion to €41.2 billion. In the first quarter of 2015, impaired loan balances were broadly stable, but asset quality showed signs of deterioration in the second quarter. The stress tests may uncover marked increases in NPLs over the stressed horizon due to the rapid deterioration of economic conditions in Greece. The NPL ratio of Cypriot banks, after capital controls were put in place reached 45%. For our part, last week we appointed BlackRock as an independent advisor on NPLs, assigned with the main tasks of elaborating a report on NPL segmentation and tabling proposals on the management of NPLs.

2. Another important issue concerns macroeconomic forecasts on the recession, deflation and unemployment under which a baseline and an adverse scenario will be used for the stress tests in order to identify potential bank capital shortfalls. As I mentioned earlier, Bank of Greece forecasts that the GDP rate will range between -0.8% and -1.3%, with an average of -1% by end-2015, deflation will stabilise at -0.5% due to VAT increases and the unemployment rate will stand at around 26-27%.

3. There is also a strong intention among stakeholders to recapitalise and consolidate cooperative banks alongside bigger systemic banks and the same applies to one less systemic institution.

C. THREE MORE ISSUES ON REBUILDING CONFIDENCE AND THE ECONOMY’S POTENTIAL

1. As President Mario Draghi pointed out in his last press conference in September, reinstating the waiver for Greek bonds will be on the ECB’s agenda, given that the country is in a programme for financial assistance and complies with it. We expect Greek banks to reduce their ELA funding worth €84 billion currently, regain access to the ECB’s normal financing operations. Once the waiver for Greek bonds is in place, Greek banks’ available eligible collateral will increase by around €15 billion, helping them to reduce their ELA dependence and find cheaper funding (through MROs, LTROs, interbank credit) and thus increasing their profitability. Furthermore, as a result of the upcoming bank recapitalisation, deposits will hopefully return after the large outflows recorded since December 2014 (estimated up to now at around €40 billion).

2. At the last ECB press conference, President Draghi hinted at the inclusion of Greek government bonds on condition that the first review of the third Greek financial assistance programme is successfully completed. Such a decision, as you understand, will help improve the outlook on the GGB market and subsequently corporate bonds and other financial markets drastically. The most natural corollary would be for Greece to be included in the ECB’s asset purchase programme (APP). This could happen towards the end of 2015 or in the first quarter of 2016. In terms of the specifics of the Greek PSPP, the Eurosystem could purchase approximately €3.5 billion before running into the 33% issuer limit. Furthermore, some additional funding could also be raised if Greek public sector non-financial institution bond issues were to be considered as eligible marketable debt instruments. Some could argue that the above amount is a mere pittance compared with the total Eurosystem’s purchased amount of €464 billion under the APP programme, with Greece’s participation being around €12 billion (PSPP = €9 billion, CBPP3 = €3 billion). Even in this respect, the signalling effect of Greece’s inclusion in the APP will be strong enough for GGB prices to recover accompanied by a significant fall in volatility, as the overall financial environment is normalised and Greece ceases to be the outlier in the euro area. It is worth simply reminding the sharp fall in the government bond spreads of peripheral euro area countries (Italy, Spain) vis-à-vis the yields of core euro area country bonds, when the ECB announced the OMT programme and their convergence after the OMT final approval from the European Court of Justice.

3. Last but not least, for a successful third and final MoU, namely one that will stabilise expectations and facilitate a sooner-than-later return to international capital markets, there is something that was missing from the first two MoUs and hopefully will be achieved this time around. As you know, there is a cumulative loss of 25% of Greece’s GDP as a result of the consolidation programmes and internal devaluation during the last five years. Capital formation has dropped by more than 60% in the last 7 years: from €20 billion in net investment in 2008 to -13 billion today (2008: €53 billion gross investment, depreciation €33 billion. 2015: €19 billion gross investment, depreciation €32 billion). So very few would disagree that the country now needs an investment shock. The question of course is where such a shock might come from, given that an adjustment programme is in place. Before going into more detail on this, let me say that there are technical ways to incorporate this investment dimension in an adjustment programme (see my article in the Wall Street Journal (2012), adding a new dimension to the two standard concepts of conditionality, namely fiscal and structural conditionality, that of investment conditionality).

I will indicatively give you one idea (out of many more): there is a strong case today in Greece in favour of a drastic cut in corporate taxes. Greek companies operate in an adverse environment. More specifically, apart from high corporate tax rates, domestic firms are burdened with high energy costs (30% above the European average) and high funding costs (lending rates that are up to four percentage points higher than in the rest of the EU). Furthermore, they are faced with intense tax competition from countries in the broader area of the Balkans (with lower corporate tax rates: 10% in Bulgaria, 12.5% in Cyprus, 16% in Romania, 20% in Turkey against 29% in Greece).

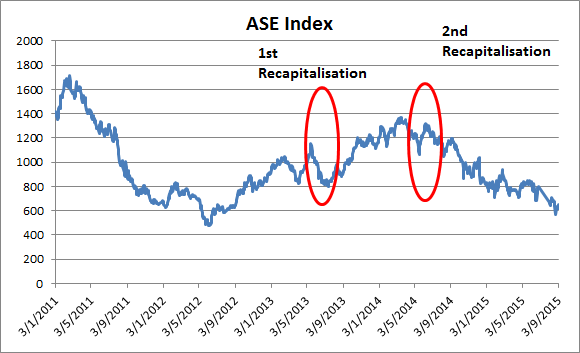

3. Current and upcoming developments in the Greek financial markets

Upon completion of the current agreement and Greece beginning to fulfil its commitments, financing and liquidity constrains for the Greek state and Greek financial and non-financial institutions will ease and Greek assets are expected to recover. My view on the direction for the Athens Stock Exchange (ASE) and the Greek government bonds (GGBs) over the medium-term is they will follow a clear upside trend not only thanks to the recently improved prospects of political stability, Greece’s QE eligibility prospects and the upcoming bank recapitalisation, but also due to the current very low market price levels.

Chart 2: Evolution of ASE Index

Sources: Bloomberg and Bank of Greece.

Since mid-2013 and following two rounds of Greek bank recapitalisation, the Athens Stock Exchange (ASE) index stood at 1400 index points, recording a return of around 75%. Unfortunately, since August 2014, the Athens Stock Exchange has lost all its gains against the background of elections, a referendum, capital controls and with the prospect of a third recapitalisation of Greek banks.

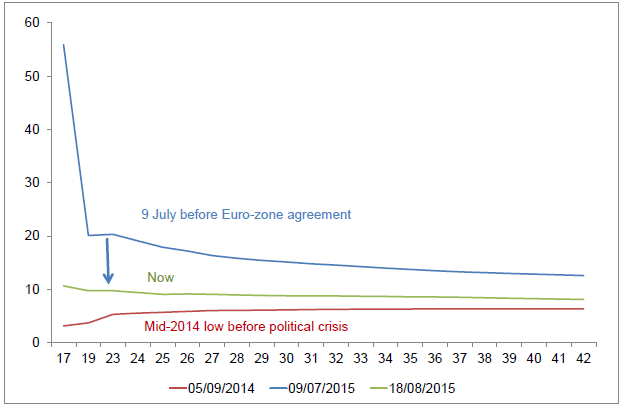

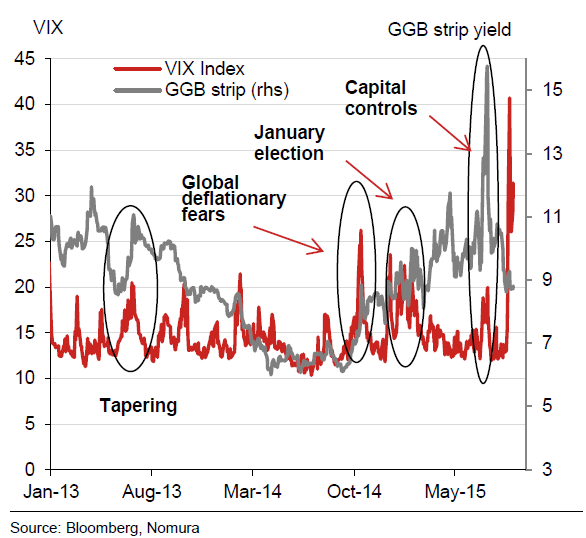

As far as the Greek government bond market is concerned, undoubtedly, the news of a deal on the new three-year bailout programme on 14 August led to a sharp rise in Greek government bond prices (see Chart 3). Overall, judging by the upcoming positive developments surrounding Greece’s QE eligibility and ruling out the risk of Greece leaving the euro area, GGBs should highly benefit. Finally, it is worth noting that the GGB market has been relatively immune to recent global risk concerns, as investors are more focused on the political normalisation which opens up brighter prospects for Greece’s future in the euro area. Looking at the volatility index (VIX) as a proxy for global risk, its recent spike to five-year highs failed to trigger any serious reaction in either GGBs or even other euro area periphery markets (see Chart 4). Moreover, investors, due to the capital outflows from the emerging markets and the recent Chinese equity turmoil could consider entering or adding to long positions in GGBs as an investment opportunity as euro area peripheral credit risks are subdued in a QE environment, while at the same time additional policy response in the form of more QE remains at the disposal of European policymakers if needed (something similar happened in 2014 which then gave rise to an early successful first return of the Greek government to international bond markets – in April 2014 – through a tentative €3 billion five-year bond issue and three months later, through another €1.5 billion three-year bond issue. At the time, a single observation was made by the Chief Economic Advisor to the PM: as a result of Fed’s tapering, lots of liquidity was coming out of emerging economies into advanced economies, including the countries of the euro area periphery).

Chart 3: GGBs yield curve after the July 2015 agreement

Source: Bloomberg.

Chart 4: Greek government bonds and volatility index (VIX)

As shown in the above chart, Greek government bonds have shown significant correlation with the Volatility Index (VIX) in October 2014, when deflationary fears grew stronger (although weakness in GGBs was also related to the then upcoming elections). A strong correlation was observed after the national parliamentary elections in January this year and again in June when the Greek referendum was announced and capital controls were imposed. The recent spike in the VIX to five-year highs failed to trigger any serious reaction in either Greek government bonds or even other euro area periphery bonds. In my view, this illustrates that global risk sentiment has a limited pass-through to periphery bond markets at this stage. In GGBs, the market seems focused (rightly in my view) on the political normalisation that is already under way, which opens up brighter prospects for Greece’s future in the euro area.

II. EUROPEAN CAPITAL MARKETS AND THE RISE IN VOLATILITY

Four are the main drivers behind heightened uncertainty and excessive volatility in European capital markets in the months ahead: the upcoming US rate rise, the possible extension of the ECB’s quantitative easing programme, the turmoil in Chinese markets together with EMEs capital outflows, and global geopolitical risks (Ukraine crisis escalation, Jihadi terrorist rise, etc.). As far as QE in the euro area is concerned, some voices in Frankfurt call for an increase in the ECB’s QE from €60 billion monthly to €80 billion or more. While ECB’s policy has been accommodative, it has been much less accommodative than other central banks. A pace of €80 billion per month, it would take until the end of 2017 for the ECB’s QE to reach the same levels relative to GDP with the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England. Others claim that the QE period should be extended beyond September 2016, implying a second round of QE in Europe. ECB President Mario Draghi himself, when asked at the last press conference in Frankfurt said: “Accordingly, the Governing Council will closely monitor all relevant incoming information. It emphasises its willingness and ability to act, if warranted, by using all the instruments available within its mandate and, in particular, recalls that the asset purchase programme provides sufficient flexibility in terms of adjusting the size, composition and duration of the programme”.

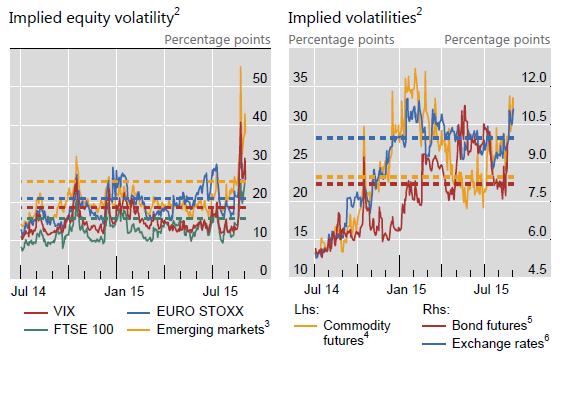

The effects of divergent monetary paths (Fed rate hike (1) vs. Draghi’s QE) would normally strengthen the value of the US dollar against the euro and would also contribute to a fall in the German Bund and other European country bond yields and to a rise in euro stocks. The Chinese market turmoil (2) together with capital outflows from emerging market economies (EMEs) and the possible escalation of a currency war after the upcoming Fed rate hike might work at opposite directions, contributing to further market volatility for European capital markets. The volatility index (VIX), which measures stock market volatility, surged to 40, its highest level since 2011, while the rise in EMEs’ implied equity volatility (VXEEM) was its highest on record (see Chart 5). It should be recalled that the 3-month correlation between EUR/USD and VIX has reached its highest level since 2009.

Chart 5: Implied volatilities in financial markets

(2) The dashed horizontal lines represent averages from 1/1/2012 to 31/12/2014. (3) Chicago Board Options Exchange- Traded Fund Volatility Index. (4) Implied Volatility of at the money options on commodity futures of Germany, Japan, the UK, and the US; weighted average based on GDP and PPP exchange rates. (5) Implied volatility of at-the-money options on long-term bond futures of Germany, Japan, UK and U.S. (6) JP Morgan VXY Global Index.

Source: Bank of International Settlements (BIS) Quarterly Review 2015.

Note: The JP Morgan VXY Global Index measures volatility in a basket of G7 countries’ currencies.

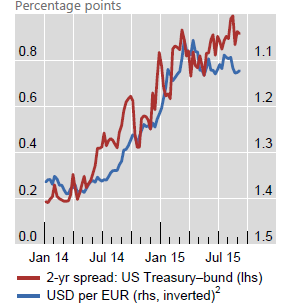

Chart 6: Widening interest rate differentials and FX

(2) A decrease on an inverted scale indicates euro depreciation.

Source: Bank of International Settlements (BIS) Quarterly Review 2015.

Although the timing of the Fed’s first tightening move in many years has become more uncertain, interest rate differentials between the US and many other countries are still wide, with important consequences for foreign exchange markets. In particular, except for a brief hiatus in the second quarter of 2015, the US dollar has been on an appreciating trend since mid-2014. The effect of interest rate differentials on the US dollar was particularly strong vis-à-vis the euro: as the difference between US and core euro area interest rates began to widen again in the third quarter of 2015, the dollar resumed its strengthening path against the euro (see Chart 6). Towards the end of the period, as US short-term rates edged down, the euro recovered somewhat. In addition, foreign-exchange volatility now stands at its highest levels since 2011 (see Chart 7).

Chart 7: JP Morgan Global FX Market Volatility Index

Sources: Bloomberg and Bank of Greece.

Note: The JP Morgan Global FX Volatility Index tracks the value of options of emerging and developed market currencies against the US dollar: New Zealand dollar, Norwegian krone, Swedish krona, Japanese yen, the euro, British pound, and Canadian US dollar.

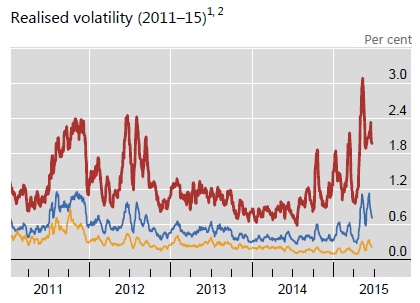

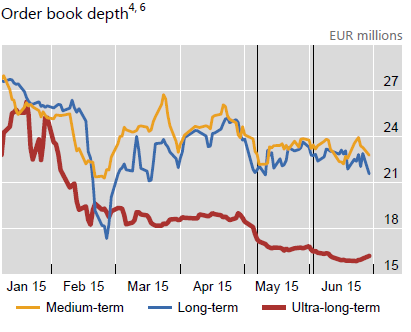

As far as bond markets are concerned, a volatility spike was evident especially in German Bund markets in May and June. German government bonds are the key driver of European government bonds, since they serve as a benchmark for a host of other government and corporate securities and thus have a systemic (European and global) influence on borrowing, investing and saving behaviour and also have spillover effects on other markets: commodities, foreign exchange and equities. Bonds with very long maturities showed the highest intraday volatility, while bonds with shorter maturities were also affected, albeit to a lesser extent (see Chart 8). The “Bund tantrum”, as some have termed the spike in German bond volatility, can be explained mainly by the deteriorated market liquidity. Measures of market liquidity, computed using firm prices for immediately executable transactions, corroborate the assumption that strained market liquidity conditions are at least partly to blame for the heightened volatility. The cost of immediately executable transactions in the Bund market increased in the period around the Bund tantrum as the bid-ask spreads have doubled in the relative bid-ask spread, from 40 to roughly 80 basis points. Also, the market’s order book depth also showed signs of deterioration over this period, falling by more than a third over the six-month period, from €25 million to roughly €16 million in ultra-long-term German bonds.

Chart 8: Volatility and liquidity during the “Bund tantrum”

(1) Realised volatility is calculated as the daily (maximum midpoint–minimum midpoint)/average price. Intraday data from the MTS Euro Benchmark Markets (MTS-EBM) for benchmark bonds only. (2) Data from January 2011 to June 2015, aggregated to a weekly average. (4) Intra-daily data from the MTS-EBM for benchmark bonds only for January–June 2015. Both panels show daily averages. (6) Depth is calculated as the (volume at bid + volume at ask)/2.

Source: Bank of International Settlements (BIS) Quarterly Review 2015.

It is fair to say that although it might be too soon to see if the Chinese turmoil will have a severe impact through trade and financial channels on the European and global economy, the Chinese turmoil remains the main challenge in the months ahead. Exports to China represent around 10% of total euro area exports in value-added terms, meaning that a significant decline in Chinese domestic demand would dent export growth. Germany, for instance, has Europe’s strongest trade ties with China, but exports to that country make up only 6.6% of total German exports, according to the German economics ministry. For the time being, however, there is not much evidence of a slowdown in exports. Apart from a potential trade impact, further China-induced turmoil on financial markets could lead to massive capital outflows from the Chinese financial markets to the European capital markets diminishing the positive effects of ECB’s quantitative easing programme. In the short run, emerging markets remain vulnerable to further declines in commodity prices and sharp appreciation of the US dollar. This could further trigger a reversal of capital flows and disruptive asset price adjustments. Between June 2014 and July 2015, capital outflows from emerging markets reached $940 billion (see NN Investment partners, FT 19 August), in contrast with $2 trillion inflows to these markets between 2008 and June 2014. Such outflows would impact on EMEs’ growth rates, thus lowering global demand. If the Chinese economy deteriorates further, lower demand will drive down oil prices which are also being translated into lower inflation rates for non-energy components and feed into inflation expectations, leading to a worsening inflation outlook and making the ECB’s inflation target more difficult to reach. If, on the one hand, the yuan depreciates further, this will add to deflationary pressures for the US and euro area, as China is the biggest import partner for both the US and the euro area. If, on the other hand, the yuan remains at its current levels, the disinflationary impact of cheaper Chinese exports will prove less than feared by some market participants, as an overall 2% depreciation partly offsets the real appreciation of the yuan over the past 12 months (more than 10%).

More generally, in the current environment of short-term rates to near zero (or even negative) levels, potential adverse shocks or policy missteps could trigger an abrupt rise in global volatility and market risk premia (which are now compressed) and a rapid erosion of policy confidence. Shocks could originate in advanced or emerging markets and, coupled with unaddressed system vulnerabilities, could lead to a global asset market disruption, a sudden drying-up of market liquidity in many asset classes and a sharp tightening of financial conditions with negative repercussions on financial stability.

APPENDIX

Here are some further thoughts on the first US rate hike and on the Chinese turmoil.

1. Fed’s rate hike

The most crucial question is: will the Federal Reserve (Fed) raise its rates this December or next year? My view is that it is not only a question of when, but perhaps more importantly a question of the trajectory of interest rates following the Fed’s rate hike, i.e. if the subsequent tightening will be shallow or steep. Of course, the exact timing is important, the last interest rate change was in late 2008, whereas the last hike was a decade ago (June 2006). However, unless you are a bond trader, the scale and length of the tightening cycle matter more.

Here are some stylised facts from previous tightening cycles in the US (twelve cycles during the last 50 years):

• the average tightening cycle duration is less than 2 years, although in the last twenty years the average duration is about one year;

• the average increase in the base interest rate is 3 percentage points;

• a recession follows about three years following the Fed’s decision to raises rates for the first time in years.

It is the path of interest rates after the first hike that matters most because this path determines how much support the economy will be getting from the Fed. So the big question this time around is whether rates will rise quickly or slowly in 2016. The answer is pretty straightforward: slowly. In the past, each Fed rate increase was soon followed by other central bank rate rises. This time, given divergent monetary paths (mainly the QE programmes in Europe and Japan), a US rate hike is expected to be followed by a US dollar appreciation, given that foreign capital will take advantage of more attractive yields driving the US currency higher and also given the US dollar’s role as a safe haven currency. This will further tighten policy since a higher exchange rate will reduce the price of imports and hence inflation. Indeed, since early January, the US dollar appreciated against the euro by more than 7% (€/US $: from 1.20 to 1.12), while it appreciated against the yen by 4% (from 119 to 124) and the British pound by 3% (from 0.64 to 0.66). The above reasoning suggests that the next US tightening cycle will be shorter and shallower than in the past. In other words, I tend to be more on the side of futures markets than of Fed officials as far as the prediction about the level of the base rate at the end of 2016 is concerned.

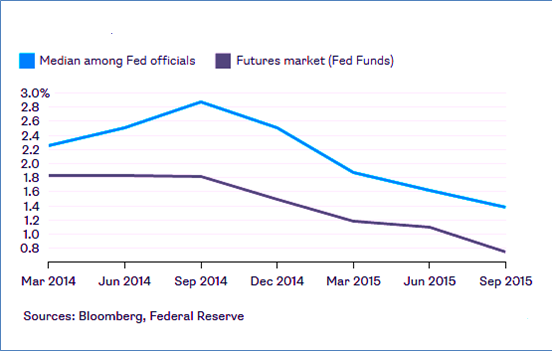

As shown in Chart 9, Fed officials think that a growing economy will allow the central bank to increase its target significantly over the following year or so and their median projection for end-2016 is 1.375%, while investor expectations derived from futures market prices hover around just 0.75%.

Chart 9: Forecasts for end-2016 Fed base rate

Of course, this first Fed rate rise in many years might have adverse effects on emerging market economies (EMEs) given the history of emerging market crises (1979-1982 in Latin America, 1994-1995 in Asia) coinciding with the early stages of US monetary tightening cycles. This time, a premature Fed tightening move would not trigger an emerging market crisis (since it has already broken out in China), but it would accentuate the crisis through spillovers to advanced economies. The most vulnerable countries are those with large fiscal and current account deficits or, to put it differently, those lacking political and policy credibility. A tightening of the Fed’s policy is likely to lead to further capital outflows from EMEs as investors search for rising returns in the US, which in turn might imply a depreciation of EMEs’ currencies, a rise in their interest rates, economic slowdown, etc.

2. The Chinese turmoil is the main challenge ahead

One last word about China and the recent market turmoil: this latest episode may have the characteristics of a regime switch towards a permanent, lower output, driven by a structural real estate overhang, chronic industrial overinvestment (45% of GDP) financed by a (collapsing) shadow banking system.

Since mid-August, financial markets have been facing substantial volatility, following China’s decision to change the methodology for setting the central fixing rate of the yuan, which led to a 2% devaluation in China’s currency, its biggest daily move since 1994. The decision was probably prompted by weakening economic activity, a decline in exports (July figures indicated a year-on-year decline by more than 8.5%), deflationary pressures and followed the depreciation of the yen and the euro, which are the major trading currencies for China. Recently released data on China’s PMI (former HSBC PMI), which dropped to 47.0 in September, its lowest level since 2009, and further deterioration in China’s activity indices (for instance, the crude steel output fell by 6.3% on a yearly basis in the first eight weeks of the third quarter) suggest that China’s official growth rate of 7% can be put under question. If macro data continue to weaken, China is not likely to maintain its recent growth rate, but it will be stabilised at a lower level, its slowest rate since 1991.

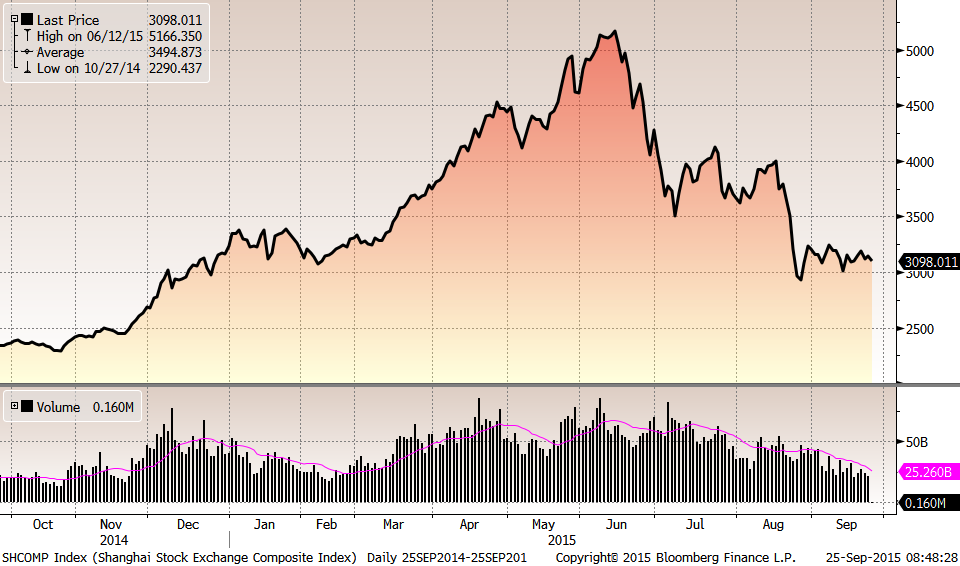

Chart 10: Shanghai Stock Exchange Composite Index & Turnover

Sources: Bloomberg and Bank of Greece.

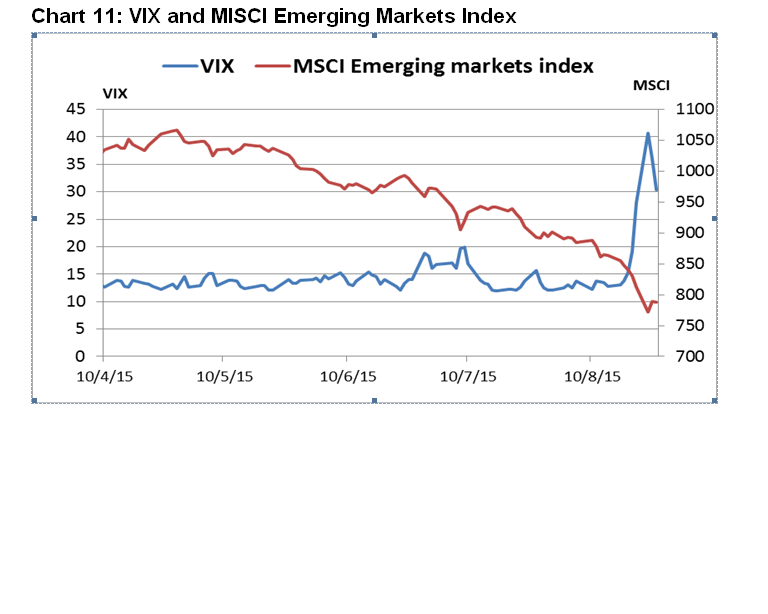

As shown in Chart 10, the Shanghai Stock Exchange Composite Index has experienced a sharp correction by roughly 40% since its June 12 peak, after it had risen around 150% in one year. Its turnover still remains below the average of US $25.2 billion. In addition, the fears of a Chinese slowdown affected emerging economies (see Chart 11) and commodity producing countries.

Sources: Bloomberg and Bank of Greece.

Notes: VIX= Volatility Index. Composition: Implied Volatility of S&P 500 options, MSCI: Morgan Stanley Capital International. Data from 21 emerging economies: Brazil, Chile, China, Colombia, Czech Republic, Egypt, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, Morocco, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Russia, South Africa, Taiwan, Thailand, and Turkey.

The Chinese slowdown affected emerging economies as it led to a massive sell-off in their equity markets and a rise in volatility which spilled over to other international markets. Spillovers were evident mainly in the foreign exchange market with emerging market currencies depreciating against the USD and safe-haven flows into the yen, Swiss franc and the euro. At the same time, high yield and emerging market bond yields widened significantly. Another important consequence was the impact of the Chinese equity crisis on commodity prices, particularly on oil (e.g. WTI Crude Futures lost as much as 36% over the last two months), which immediately triggered expectations of global disinflation with potential implications for future central bank actions. Nevertheless, it seems premature to conclude whether this, or a further, yuan depreciation would feed into imported disinflation in the US, Europe and Japan. Contagion spread to advanced economies’ equity markets and, despite some gains in late August, the overall levels remain lower than two months ago.

* This is the text version of the powerpoint presentation used by the author for his meeting with international investors and analysts in New York (7 October 2015) organised by Redburn Access.