Keynote speech by Bank of Greece Deputy Governor John (Iannis) Mourmouras entitled: “Post-MoU Greece: Five proposals” at the 2nd International Conference of the Economic Chamber of Greece at the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center (Athens)

31/05/2018 - Speeches

Your Excellency, Mr. President of the Hellenic Republic,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Introduction

After 8 years of hardship and thanks, on the one hand, to the big sacrifices of the Greek people and, on the other hand, to the solidarity of our European partners as this is manifested by the unprecedented amount of loans given to our country on truly concessional terms (very low rates and long maturities), Greece is finally coming out of the tunnel with optimism. Although the international economic environment and indeed the situation in our neighbourhood is pretty unstable right now, I believe the Greek case is manageable for an exit from the MoUs in late August without a precautionary credit line – which would be effectively a mini-fourth MoU. Such an exit, after all, would be similar to the cases of Portugal, Ireland and Cyprus. I will seize the opportunity of this conference organised by the Economic Chamber of Greece, thriving under the leadership of Konstantinos Kollias, taking place in this magnificent masterpiece of world architecture named after a global business leader, Stavros Niarchos, to make 4 new proposals, and repeat an old one, towards achieving this sort of exit and beyond, and the emphasis is on the “beyond”. Then I will briefly ask what went wrong in the case of Greece. I have written extensively on this subject during the period 2010-2014 with my previous hats, including the professorial one. The important thing is to look forward, but history matters and the lessons drawn with regard to member countries of monetary unions are of paramount importance. And finally I will look at the significant role that the ECB played in the adjustment programmes in the four countries and, more generally, in the South of Europe (including Spain and Italy), among other things in providing liquidity and effectively saving the euro, because, as you know, that was at stake in the end.

Before coming to the main topic of my speech, five proposals on post-MoU Greece, a digression may be in order on Italy.

Italy

What’s happening in Italy right now is not a surprise for some. For a lot of analysts it has the potential to trigger the next global financial crisis after 2008, markets’ first reaction was really dramatic, although the following days they seem to be calming down a bit. US and European equity markets fell by around 2% on the very first day, the Italian 2-year government bond rose by 230 basis points, the Italian 10-year government bond rose by 70 basis points, a trend not seen since the euro area crisis in 2012 and dragging down all other europeriphery government bonds. The unstable political situation caused by populists, which has left the country without a government since March, goes back to two major root causes. First of all, it may be attributed to the failure of globalisation to reach some segments of the population, which have been left behind in terms of its economic benefits, for instance through chronic unemployment of around 11%, with youth unemployment at a devastating 35%. Italy’s per capita income is lower today than on the eve of the country’s euro adoption in 1999 and over the past decade, the country has experienced a triple-dip recession. It is expected to be at the bottom of the euro area’s growth league this year. It is no wonder that the 5 Star movement won more than 50% of votes in the troubled south, where poverty rates have increased by half since the crisis.Secondly, increased migration flows in the last three years, triggered a strong anti-European sentiment and broader support for populist forces.

Italy is too big to ignore. Its GDP is 10 times bigger than the Greek one. Italy is the eurozone’s third-largest economy and it has systemic importance to the world economy. Italy has the world’s third largest sovereign debt market, after the US and Japan, with total public debt of more than €2.3 trillion, of which more than 36% is held by foreigners, so contagion is really an issue here. It also has the worst public debt-to-GDP ratio (133%) in the eurozone after Greece and a weak banking system, poorly capitalised, troubled also by the high level of non-performing loans (more than €250 billion, 15% of the total). No matter what happens with the current political and constitutional crisis in Italy, the problem with Italy was there: life after QE, namely what happens with the end of QE this year when the ECB will stop its large-scale purchases of Italian government bonds. I don’t want to think what would be happening if political developments were to lead Italy to lose its investment grade (currently at BBB).

A. Greece today and beyond

A.1 The real economy: positive short and medium-term outlook

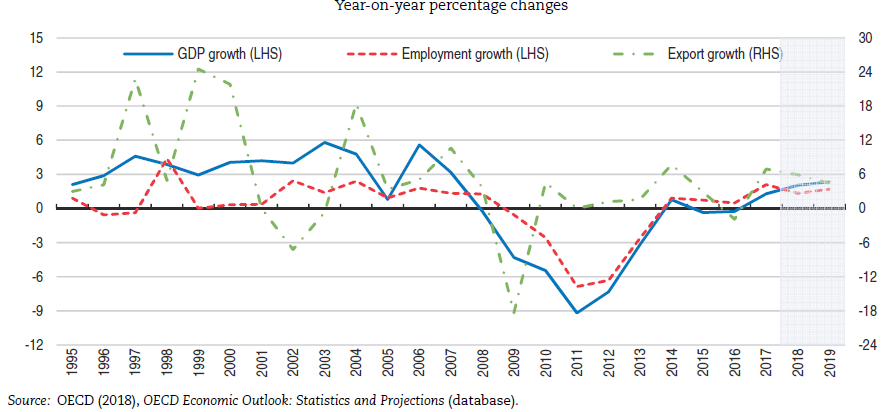

Greece’s economic recovery is finally gaining traction after an unprecedented depression. Real GDP in 2017 increased by 1.4% with positive contributions from exports of goods and services (2 percentage points contribution) and gross fixed capital formation (1.2 percentage points contribution) (see Chart 1). This positive outcome creates a strong carryover effect of +0.5% for GDP growth in 2018, which supports the outlook for a GDP growth rate of around 2% and 2.5% in 2018 and 2019, respectively.

Figure 1 Growth has resumed

Positive developments are not only reflected in economic activity indicators, but also in soft data such as the manufacturing PMI which has been in expansionary territory for the last ten months, by far the longest period since 2007. Economic sentiment has been on an upward trend since mid-2015, reached a 3-year high in 2017 and further improved in the first quarter of 2018. Industrial production has been expanding at healthy rates since mid-2015 and performed exceptionally well in 2017.

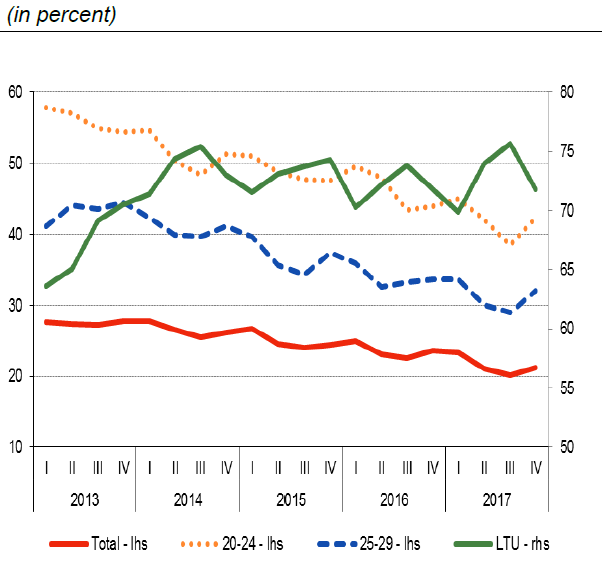

The unemployment rate dropped to 21% in 2017, falling by around 6 percentage points from its peak in 2013. This trend continued in the first four months of 2018, which supports the outlook for an unemployment rate of around 19% and 18% in 2018 and 2019 respectively. Employment increased by 2.2% in 2017, and the number of unemployed declined by 9.2%, while the youth unemployment rate (in the 20-29 age category) declined to 35% in 2017 from 38% in 2016, and long-term unemployment also dropped by 3 percentage points (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Total, youth unemployment rate and share of the long-term unemployed (in percentages)

Source: ELSTAT, Labour Force Survey.

The Greek banking sector is strengthening

Turning now to the Greek banking sector, first allow me to make some comments in the wake of the stress test results. All four systemic banks successfully concluded the 2018 stress test conducted by the ECB, pointing to no capital shortfall. Therefore, for the first time since 2010 and after three rounds of capital injections in the last five years, the Greek banks will not need additional capital in the near future. More analytically, the tests revealed a 9 percentage point impact on banks CET1 ratio under the adverse scenario, equivalent to €15.5 billion, but left all banks’ CET1 higher than the 5.5% implicit hurdle (although one bank is relatively close and is expected to continue its current capital plan).

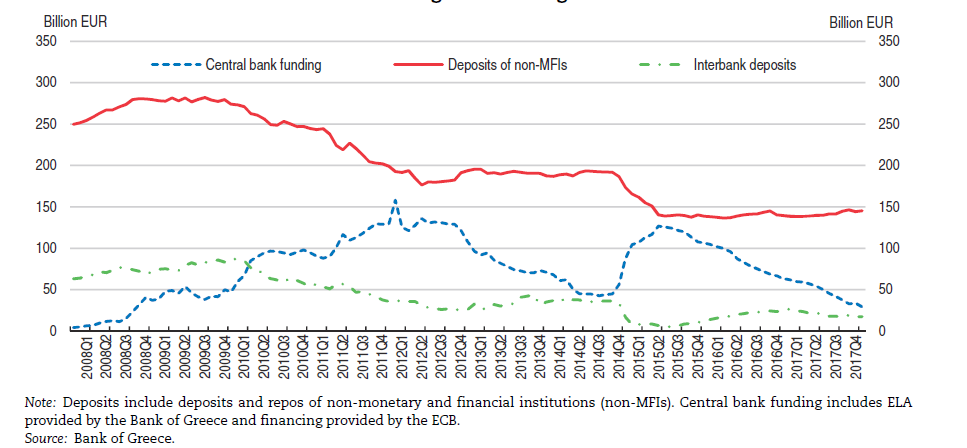

Moreover, the continued improvement in the banking sector can also be seen on their reduced reliance on the central bank funding, which is diminishing steadily and is now below the levels of end-2014 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 Bank deposits and reliance on central bank funding (Q1 2008 to end-February 2018)

Banks’ dependence on the ELA emergency lifeline has declined significantly to around €8.6 billion during this month, from €70 billion at the end of 2015 and is expected to be terminated before the end of the year. Another visible improvement in the Greek banking sector was the increase of the total deposits between end-June 2015 and March 2018 by €13 billion (or 8.0%) to €143 billion.

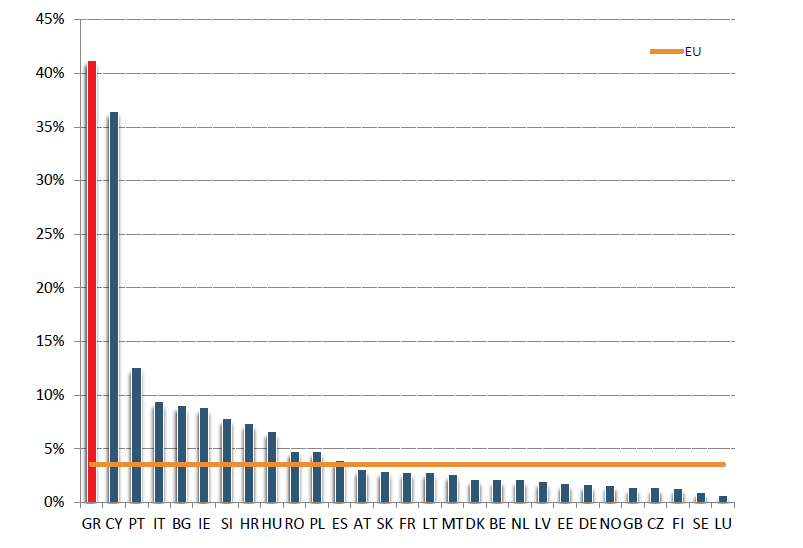

Last but not least, a major pending issue is the tackling of the problem posed by the high stock of non-performing loans, the ‘Achilles heel’ of the Greek banking system.

On a positive note, for the first time since 2014, net NPEs follow a downward trend. However, the NPE ratio of 42% in Greece remains the highest across euro area countries, against 14% in Portugal and 10% in Italy and Ireland (see Figure 4), while before the crisis the NPL ratio in Greece was 4.5% (in 2007), against 3% for the euro area average.

Figure 4 Ratio of non-performing exposures (NPE ratio) in the euro area (December 2017)

A.2 Post-MoU Greece: the way forward

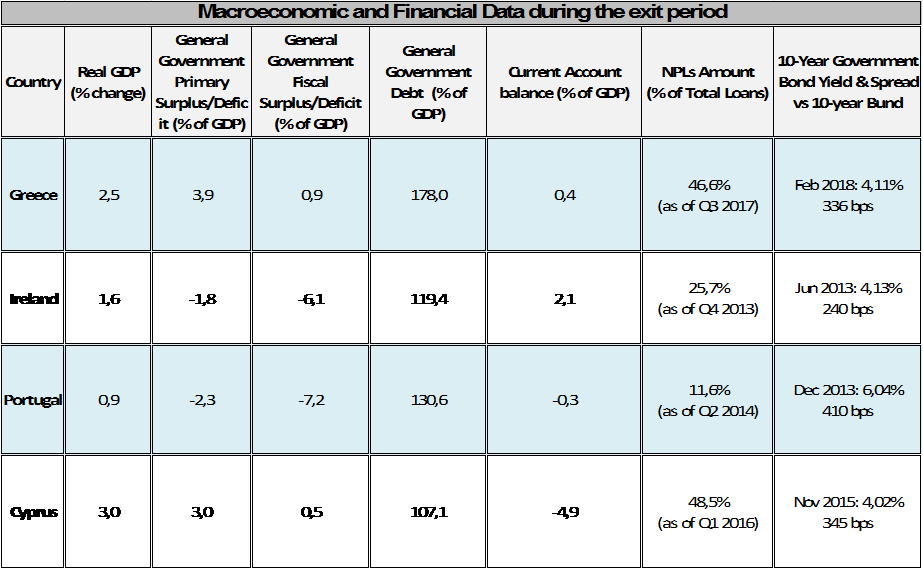

First of all, as shown in the following table, Greece has outperformed – with the exception of NPEs and public debt, in terms of all other macroeconomic indices – i.e. in terms of growth, primary and fiscal surplus, current account surplus, the spread of Greek bonds vs. the German Bund – the other 3 countries during the corresponding exit periods. This is obviously comforting to both our lenders and the markets for the future of Greece after the MoUs.

Table 1

Source: Bank of Greece.

I intend to skip here the latest heated debate on cash buffers vs. a precautionary credit line, for 2 reasons. Firstly, they are both short-term solutions, maximum one plus one year, but the real question remains what comes next after the first post MoU-year. This is the question I propose to focus on, namely: what needs to be done in order for the country to achieve a permanent sustainable return to the capital markets, like the pre-2008 status. It will be the sequel question to either cash buffer or precautionary credit line the country will inevitably have to face in a year or so. I want to open this debate from here today by making a number of proposals that will make such a return feasible in the foreseeable future. Secondly, this economic debate has turned into a saga, it’s a politically controversial issue, as it is quite often the case in Greece, some have called it ‘sour grapes’ – and I don’t want to go into that territory. The truth of the matter is that we have in our hands a Eurogroup decision of 15 June 2017, which is an agreement between the government and our lenders in view of the ending of the current programme in August 2018 and I quote: “Europe commits to provide support for Greece’s return to the market …” and “to further build up cash buffers to support investors’ confidence and facilitate market access”.

Right now we have this agreement. If this changes, we are here to discuss it.

Before coming to my proposals, let me list a number of undeniable facts about post-MoU Greece:

- The fourth and final programme review has been concluded successfully last week. So the last disbursement from the ESM is only a matter of time and, as of today, there will be no extension of the third adjustment programme, which ends on 20 August later this year.

- Any prior actions left will be dealt with during the post-MoU period, known as the Post-Programme Surveillance (PPS). We know the name, but not what it will entail. This is the big known-unknown today, be patient and we will know all about it in a few weeks’ time.

- What is clear, however, have no doubt about it, is that Greece will be exiting the 3rd MoU, but will be entering something new, not a 4th MoU, but something hybrid with conditionality since debt relief, according to all evidence, will be given in tranches.

- Finally, it seems that austerity will stay with us at least for another 4 years as primary surpluses of 3.5% are required until 2022.

Before turning to my own proposals for Greece, one word about the IMF. It is not clear yet what role the IMF holds for itself. Any IMF decision about its future role will be fully respected. There is a proposal already, which I endorse, that Greece’s remaining loan obligation to the IMF of €10 billion which comes at a gross interest rate of 3.8%, much higher than European loans interest rate of about 1%, should be repaid immediately (the money can be found). Such an early repayment of the IMF loan would contribute to an improvement of the sustainability of public debt, making also possible a more balanced management of payments.

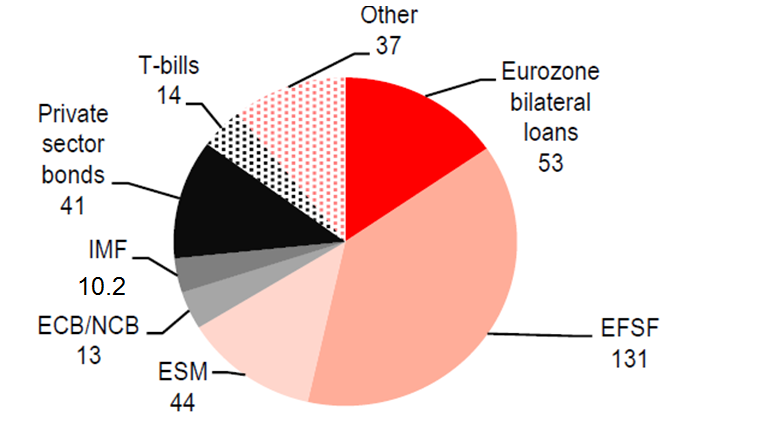

Figure 5 Greece public sector outstanding debt (in billion euro)

Sources: HSBC and Greek Public Debt Management Authority (PDMA), January 2018.

Then all past grave mistakes by the IMF (e.g. on the value of fiscal multipliers, assumed at 0.5, when the correct value was 1.5), the over-optimistic forecasts about growth and fiscal surpluses under the 1st MoU, turned into over-pessimistic forecasts under the 3rd MoU, etc. and the most recent ones, like e.g. that the Greek banks will need at least €10 billion capital injection as a result of the 2018 stress tests, will be “all forgiven and forgotten”, as they say.

Of course, a key prerequisite for a permanent return to the capital markets is the sustainable recovery of the Greek economy with growth levels of above 2%. On top of that and from my point of view, the following four proposals are also required:

Proposal #1: Further increasing the cash buffer

The government’s strategy - agreed with our lenders - makes sense: to fully cover the country’s financing needs for the first post-MoU period. This is after all what all the other three countries did. For instance, in the case of Ireland, it was a cash buffer of €25 billion, in Portugal it was around €20 billion, in both cases around 13% of their GDP. Greece’s gross financing needs for the next two years amount to €45 billion, of which €18 billion will be covered by the primary surplus and the privatisation agenda, and there is an existing cash buffer already from the 2018 debt issues and from repos.

My personal view is that due to:

a) adverse capital market conditions globally, the return of volatility and higher oil prices, inverted US yield curves as a result of monetary policy tightening, the widening Libor-OIS spreads, which exert pressure on the US dollar money market, the recent US dollar strength vis-à-vis other main currencies. All the above might have a greater impact on vulnerable countries with low credit ratings and weaker economies.

Name it, Italy as described above or Trump’s trade war with China and other major economies, the fog of uncertainty has thickened.

b) Also due to political developments in Greece as next year will be the year of European elections and also national and regional elections. Plus there are also geopolitical risks in our neighbourhood (our unpredictable eastern neighbour in connection with the drilling of gas in the Aegean and Cyprus).

All the above make a strong case for increasing the buffer as much as possible for shielding the economy. Large cash buffers boosted investor confidence and have aided market re-entry in Ireland, Portugal and Cyprus. The extra money could come from either the bank recapitalisation amount remaining from the 3rd programme, or from new issues in the markets over the next 3 months, provided that the dust in capital markets settles down.

If things turn nasty in Italy and the europeriphery, in the next few weeks, there is plenty of time for the Greek government to negotiate with our European partners, a negotiation which I would suggest to be made at the highest level, at Prime Minister level, for Greece to exhaust all the remaining amount, which is more than €25 billion, from the €86 billion of the 3rd programme, leaving not even a single euro in the account. This amount has already been approved by the national parliaments in eurozone countries, if we face an extraordinary situation due to external factors, it is only prudent for Greece and our lenders to secure the maximum reserve amount for a rainy day in order to shield the country. There is still plenty of time for the government to look at this. Just keep a cool head!

Proposal #2: From debt sustainability… to obtaining the investment grade for Greek public debt

We have every confidence that our lenders will keep their word on providing Greece with further debt relief - pacta sunt servanda applies to both lenders and borrowers - and deliver on what they promised since November 2012. The debt relief measures described in the Eurogroup statement of 15 June 2017 need to be clarified and specified with a clear timetable to be considered credible by investors. It will be along the lines of the 1st package of short-run measures, i.e. extending maturities and lowering interest rates which, given the new debt metric “gross financing needs below 15% of GDP for the medium term and below 20% of GDP thereafter” would make sure that the Greek public debt is sustainable. The new debt metric that focuses on gross financing needs (GFNS) – rather than the old one of nominal debt-to-GDP ratio – captures adequately the concessional terms of loans to Greece by the EFSF and the ESM (more than €180 billion with maturities up to 32.5 years and a fixed rate close to 2% directly or indirectly taking as a basis a near-zero borrowing rate from the markets by the ESM). Reducing public debt in present value terms puts the profile of Greek debt in an advantageous position among two thirds of eurozone countries and four fifths of EU countries.

With the end of the programme in August and the specification of debt relief measures in June or July Eurogroup meetings, and a positive DSA report – I open brackets here (recalling that “the one who pays the piper calls the tune”, the ESM from which we borrowed more than €180 billion as of today naturally prepares a debt sustainability analysis (DSA), which will most likely be signed by Dr. Strauch, Chief Economist of the ESM, whom we have the pleasure to have with us today – close brackets) one should normally expect at least a two-notch improvement in the country’s credit ratings by the relevant agencies. This would still be far from the investment grade of BBB-, but, here is my proposal: a new advisory Task Force with senior figures from the Public Debt Management Agency (PDMA), the General Accounting Office and the Bank of Greece, headed by an established figure with an international reputation, would join forces to help obtain the investment grade asap by lobbying the analysts, making roadshows abroad to investors, etc. Clearly, with the permanent removal of the capital controls (I’ll say more on this in a minute) and the elimination of ELA at the end of the year for our commercial banks, that would give another notch up in ratings, plus perhaps an overshooting of the target primary surplus - first evidence from Q1 suggest that this may reach 5% of GDP this year (from a target of 3.5%) and/or a better-than-expected growth performance due say to another record of tourist arrivals, etc. Then, the investment grade may be within reach during the next 12 months or so. I dare say this: For the country to move forward and avoid setbacks in the future, the importance of getting the investment grade in a reasonable time ahead is as important as meeting the Maastricht nominal criteria was in the 1990s, prior to Greece’s entry in the eurozone. We managed to do so then with a delay of two years. It may sound a bit optimistic today, but my motivation is to open up the discussion on this and make it a central part of the policy debate in post-MoU Greece. I believe it is feasible, and it is only fair for the country.

Proposal #3: Greece’s participation in the ECB’s QE programme during the re-investment period

With 3-4 notches up in the next 8 to 12 months and the investment grade for Greece within reach, the ECB may potentially examine the purchase of Greek government bonds under its public sector purchase programme during the reinvestment period, which will last for at least two years (end-2020).

Even though the potential purchase volumes of Greek debt today (around €3-4 billion) under the ECB’s asset purchase programme cannot be compared with those of Portugal, currently around €33 billion or Ireland’s €27 billion, yet, Greece’s inclusion in the ECB’s QE programme would yield a major boost in terms of confidence and send a positive signal to investors that Greece is not anymore an outlier, it is included in President Draghi’s umbrella with clear benefits in terms of the cost of borrowing of both sovereign and bank and corporate debt, as it was the case for post-MoU Ireland and Portugal. Note that if, as part of the upcoming debt relief measures, there will be a buy-out of ANFAs and SMP bonds by the ESM, releasing a total amount of €13 billion, then the volume potentially to be purchased under the QE programme could increase to €16 billion, which is more than one third of marketable debt, triggering a drop of even 150 basis points in the secondary market. We bought at the Bank of Greece - more than €50 billion - as part of QE, mainly supranational, hopefully the time of buying also GGBs is also near.

Proposal #4: Towards a permanent lifting of capital controls

No return to the markets can be permanent and hence credible with capital controls still imposed on the economy. The government, in cooperation with the Bank of Greece would have sooner than later, and definitely close to the end of the programme, publish a roadmap detailing the specific measures and set dates for the full lifting of capital controls, signalling also the end-date. This would be the catalyst for the full recovery of trust of depositors and the return of around €20 billion hoarded in mattresses and safety deposits, but also boost investor confidence in the prospects of the economy.

B. What went wrong in Greece?

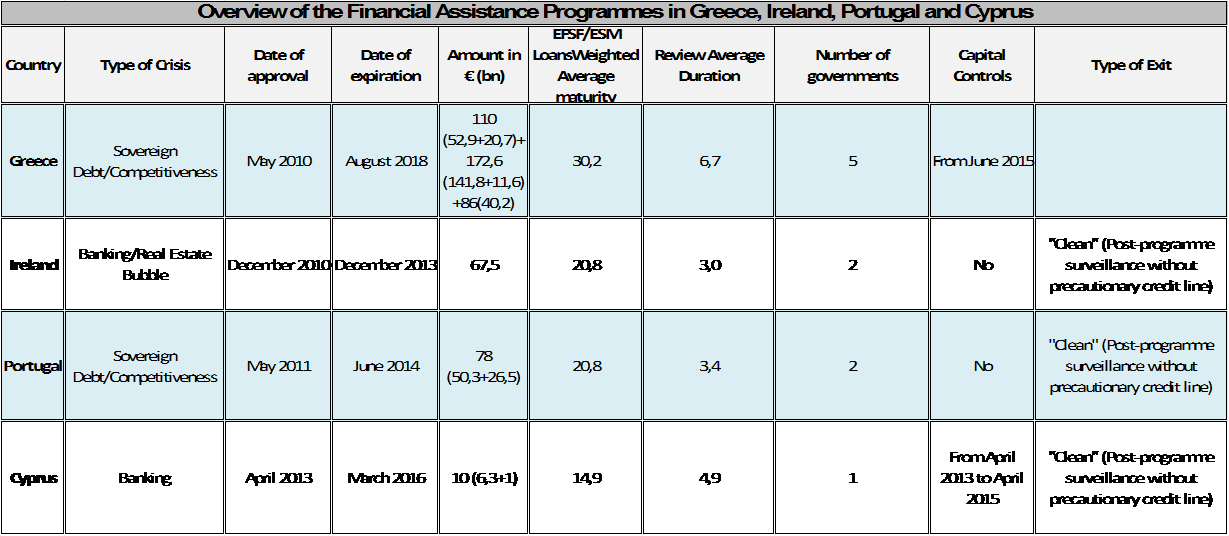

Let me now turn briefly to the four adjustment programmes that took place in the eurozone, by focusing on the question “what went wrong in Greece”. The distinguished panellists of the previous session have debated at length and elaborated on the very significant question of their countries’ experiences with adjustment programmes. The Table below summarises a number of characteristics of these programmes in the europeriphery (see Table 2).

Table 2 Overview of the Financial Assistance Programmes in Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Cyprus

Source: Bank of Greece.

With a naked eye, one can see in the following table that Greece has received about €240 billion from all three programmes up to now, while the other countries have received much lower amounts, Ireland €67.5 billion, Portugal €76.8 billion and Cyprus €7.3 billion. While it is widely believed that the euro area crisis started from Greece, incidentally the first sign of crisis within the euro area appeared in Ireland after Bear Sterns was rescued in March 2008, whereby Irish sovereign spreads started to diverge noticeably. Nine months later, in December 2009, there was heightened pressure on GGBs. Greece was the first country though within the euro area to sign a financial assistance programme, and unfortunately the last one to exit from such a programme.

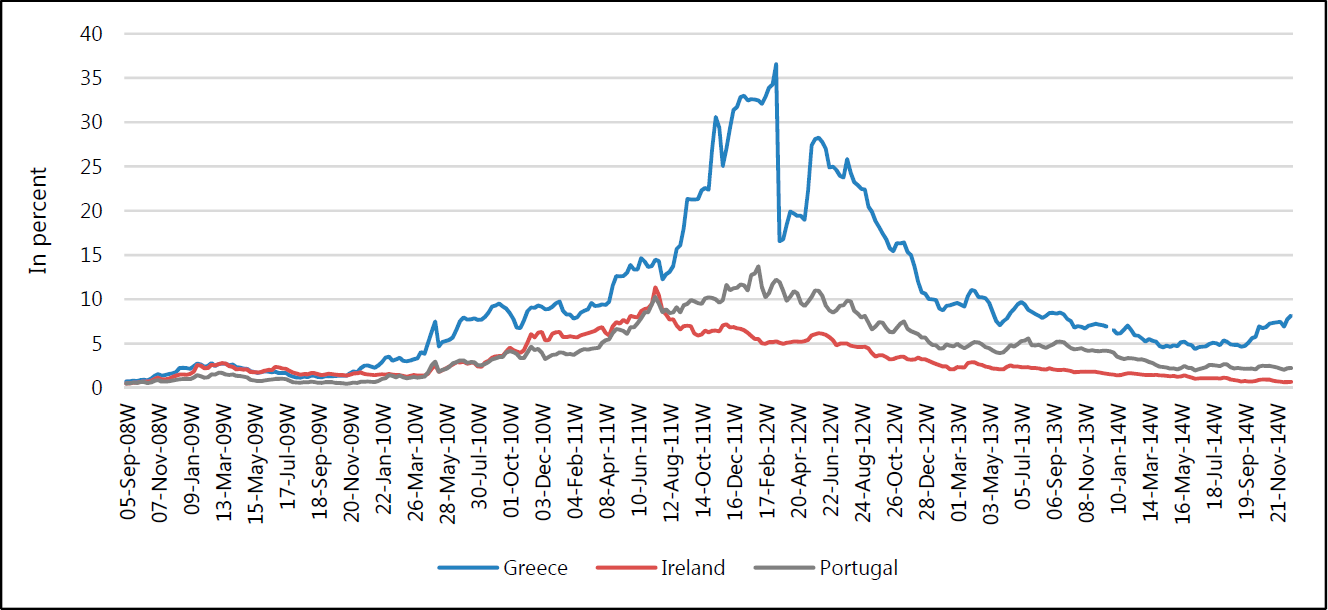

Figure 6 Ten-year government bond yields in euro area crisis countries vis-à-vis German Bund yields (September 2008-December 2014, in percentage points)

Source: Haver Analytics.

During this period, Greece experienced a dramatic fall in output (more than 25%), the unemployment ratio almost tripled from 9% in 208 to 26% in 2015, a huge fall in the standards of living and valuations of assets (real and financial) and another mountain of private debt had been built up (around €220 billion in 7 years). So, what went wrong in Greece? There are several reasons for this, let me name just a few: the starting-point argument (a huge deficit that required a bold adjustment effort); errors in the design of the programme that include the mix of adjustment measures (a greater reliance on tax increases than public spending cuts), the value of fiscal multipliers that we show above, etc., the slow pace of implementation of structural reforms (due to a lack of programme ownership on behalf of Greek authorities); the fact that Greece is a relatively closed economy and, hence, internal devaluation may contribute negatively, in net terms, to economic activity, the fact that debt restructuring in 2012 should have occurred much sooner, i.e. at the beginning of the first MoU in 2010, a directionless economic governance in the first half of 2015 and the ensuing huge cost of the economy’s backtracking, we lost valuable time then, which led to the imposition of capital controls, a severe distortion upon the economy; the wrong sequencing of reforms: product market reforms should come first, followed by labour market reforms, the exact opposite took place in Greece (Hardouvelis).

On top of the above reasons which are more or less commonly accepted, I would add a couple of other - rather technical and more subtle - reasons and this is my contribution to the relevant debate. Firstly, as we know, fiscal consolidation took place through the targeting of a nominal variable, i.e. the overall fiscal deficit which is cyclical. Taking permanent austerity measures to reduce the cyclical deficit only deepens and prolongs a recession, it results in excessive austerity and overtaxation which is self-defeating (it raises less government revenues). Instead, the structural deficit should be the appropriate target variable, and the cyclical deficit would correct itself through the economy’s automatic fiscal stabilisers, provided that growth-enhancing measures supplement fiscal consolidation (Mourmouras, FT, 2012). Secondly, there is a certain misperception in the MoUs about how reforms would work in the economy. I identify two grey areas here: (i) reforms take time to unlock their growth potential and their results are also country-specific. A recent study by the OECD (2014) indicates that the above time period may extend to five years or more; (ii) structural reforms work better and quicker when there is investment to capitalise on them and, more generally, demand in the economy because the more the recession lingers on, the harder it is to achieve positive results by implementing structural reforms. Such a demand element can be incorporated into an adjustment programme in monetary unions through the adoption of a broader concept of conditionality, namely that of investment conditionality, along with fiscal and structural conditionalities (Mourmouras, WSJ, 2012).

These are important lessons to be drawn from the Greek experience, and hopefully this will be taken into account in the design and implementation of future adjustment programmes in monetary unions.

Truly, in the last year or so, we have witnessed a revival of the Greek economy through the stabilisation of expectations and the gradual restoration of confidence. Looking forward now, we all agree that given the prolonged fiscal consolidation and private disinvestment that took place (2007: investment was 27% of GDP, today it is 11% of GDP, the lowest level since 1960), the country needs an investment shock. Reviving domestic and foreign investment is crucial to supporting the economic recovery. That is why it is important for the government to speed up the privatisation agenda, not so much as a revenue exercise, but as a great opportunity to attract FDI in key sectors of the economy, such as transport, energy, logistics and tourism.

In this respect, let me come back to an old proposal of mine, as my fifth proposal today, made back in the summer of 2014, before joining the Central Bank (see Mourmouras, The Double Crisis – Volume 2, Chapter 18: first of all, we should all agree on the limits of overtaxation. For instance, with regard to corporate taxation in Greece, 29% corporate tax (plus a 10% tax on dividends), tax competition from other countries is very intense, e.g. from the Iberian peninsula with an average tax rate of 20% (Spain and Portugal), the Baltic countries with an average tax rate of 15% (Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia) and the Balkans with an average of 10% (Turkey 20%, Romania 20%, Albania 15%, Cyprus 12.5%, Bulgaria 10% and FYROM 10%). Hence, there is a strong case to be made in Greece in favour of a drastic gradual reduction of corporate tax rates starting in 2020, but to be announced fairly soon, ultimately reaching a flat tax rate of 15% and remain locked at the same level for another five years. The drastic reduction in corporate tax rates and the commitment to leave them unchanged for a period of five years will be the best signal to Greek and foreign investors that the Greek authorities are now seeking to change the country’s growth paradigm and move towards a dynamic economy based on private investment and exports.

This drop in taxes could be financed by the fiscal space achieved through a decrease in primary surpluses, say, to 2.5% from 2020 onwards, bringing effectively forward a year or two the agreed-with-our-lenders lower primary surpluses, or from a persistent overshooting of agreed surplus targets of 3.5% of GDP until 2022.

Much to my delight, the above proposal that links lower corporate taxes to lower primary surpluses has been adopted by the Bank of Greece in May 2016 and by the main opposition leader at DETH in Thessaloniki in September 2016.

C. The role of the ECB in countries under adjustment programmes

As the euro area crisis was triggered by either a weak fiscal position in some cases or a weak banking system in others, it led to the “negative feedback loop” between banks and sovereigns, which the ECB emerged as the institution best equipped to tackle. It has used all the appropriate instruments at its disposal in order to ensure its primary priorities: price and financial stability across the euro area.

C.1 The role of the ECB on price stability

- Reducing base rates

First of all, and since the emerging of the financial crisis in 2008, the ECB has reduced its main refinancing rate from 4.25% to 0%, the largest cut ever decided over such a short period in Europe, and also brought the interest rate paid on banks’ deposits of excess reserves with the Eurosystem to negative territory, -0.40% today.

- SMP programme

Furthermore, as sovereign bond markets in some euro area jurisdictions were becoming increasingly dysfunctional, in May 2010 the ECB approved the Securities Market Programme (SMP) worth €210 billion. Its main effect was to cut refinancing costs for countries whose bonds were sold at unsustainable interest rates on international markets, leaving at the same time the money supply unchanged through sterilisation.

- LTROs and TLTROs

In December 2011, the ECB revived the longer-term refinancing instrument making the central bank liquidity available to banks for up to three years at a fixed annual interest rate of about 1%. The total allotted amount to the euro area banks was €1 trillion. In 2014, the ECB announced two more series of targeted long-term refinancing operations with a maturity of up to four years with practically zero interest rate, amounting to more than €700 billion, affecting directly borrowing conditions of enterprises in the euro area.

- Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT)

As the crisis progressed and became more intensive at the beginning of 2012, spreads in the euro area government bond markets continued to widen, i.e. Spain’s 10-year government bond rose from 5% in March 2012 to 7.6% in July 2012. In the summer of 2012, President Draghi in his speech in London declared that the ECB, within its mandate, was prepared to do whatever it takes in order to preserve the euro, repeating the irreversibility of the euro currency, the three famous words “whatever it takes” that made him the second most influential Roman ever, after Julius Caesar with his three famous words “veni, vidi, vici”! Following that speech, the ECB developed a more structured policy of the sovereign bonds market announcing the Outright Monetary Transactions programme (OMT). How much money the ECB spent for this OMT programme so far? Zero euro!!! It is the powerful impact of credible policy announcements.

- Quantitative Easing (QE)

Due to the headwinds coming primarily from the international economy, the inflation outlook in the euro area continued to deteriorate in the summer and autumn of 2014 something that threatened to destabilise long-term inflation expectations, putting the forbidden letter “D”, “D” for deflation, in the mouths of international investors.

As a result, in January 2015 the Governing Council announced the expanded asset purchase programme (APP), which included a large-scale purchase programme targeting government securities (PSPP) of €60 billion each month until September 2016. Currently, the Eurosystem holdings under the expanded asset purchase programme amount to around €2.4 trillion or 20% of euro area GDP (PSPP is worth almost €2 trillion, the remaining amount concerns covered bonds and asset-backed securities).

The positive effects of QE are mostly reflected in sovereign bond yields, the growth rate of loans and bank lending rates, and of course avoiding deflation in the euro area.area (see Mourmouras, Speeches on Monetary Policy and Global Capital Markets, 2017, Chapter 4).

- Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA)

Also, Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) has been provided by national central banks in order to help domestic banks with liquidity shortages and prevent a domino effect. Hence, between 2010 and 2014, ELA had been extended to banks in Ireland, Greece, Cyprus, and Portugal, with the Eurosystem borrowing to these countries through ELA, surpassing €200 billion. In Greece, ELA has been provided by the Bank of Greece over the last eight years and reached its peak of €120 billion in March 2012.

- The Eurosystem Resolution Liquidity (ERL) tool

Last but not least, the ECB is considering now a new policy tool, the Eurosystem Resolution Liquidity (ERL) tool that would allow it to inject cash into banks under resolution, in other words, when are being rescued from the threat of insolvency. The ERL should be seen as a monetary policy tool, ensuring the banking system can transmit official interest rates to the real economy.

C.2 The role of the ECB on financial stability

On June 2012, the European Council reached an agreement about the creation of the European framework for banks’ supervision through the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM), which forms the first pillar of the Banking Union. The ECB has been assigned specific tasks to be carried out through the SSM like for instance, to ensure the safety and soundness of the European banking system, increase financial integration and stability and ensure consistent supervision. Currently, the ECB is directly supervising 118 “systemically significant banks”, representing almost 82% of total banking assets in the euro area and indirectly supervises less significant banks in the participating countries, which number approximately 3,500 in the euro area!

It’s the same SSM, chaired by Danièle Nouy, which conducted the latest stress tests in Greek banks, the results of which came out last month. Two weeks ago, during her recent visit at the Bank of Greece, Chair Nouy emphasised to us that Greek banks need to do more to reduce their very high stock of non-performing loans (NPLs), highlighting that this is the biggest challenge facing the banking sector in the country exiting its third bailout programme in August.

D. Concluding remarks

Instead of an epilogue, I would like to close my speech with a question from the future, “back to the future”: So with all the above crisis-management tools available, is the euro area today in a better position vis-à-vis 2008 to tackle the next crisis, which, by the way, may be just around the corner? I already talked about Italy in my introduction.

With monetary policy reaching its limits, namely, negative rates (in 2008, the base rate was +4%, today it is negative) and the trillions bought by the ECB through its QE programme, and the scarcity issue which naturally arises, clearly, monetary policy can’t be the “only game in town” during the next crisis. In that eventuality, there will be hopefully a more active role for fiscal policy with more fiscal backstops to be implemented, moving also towards more risk-sharing in the euro area. Many people, including myself, feel that we need to strike a balance in the classic struggle between solidarity and national responsibility, or the ‘new wine in the same old bottle’, namely risk-sharing (namely mutualisation of costs) versus risk reduction. Especially in the South of Europe, there is a strong feeling that this balance is unstable and in order to make it more stable and more symmetrical, what is needed are stronger European institutions, for instance, a full-blown Banking Union and the ESM being turned into a proper European Monetary Fund. It is important to bring forward the date of the establishment of the European Deposit Insurance Scheme (EDIS), the Banking Union’s third pillar, which is scheduled for 2025, providing stronger and more uniform deposit insurance cover. Even the announcement of the entry into full operation of EDIS will have a strong confidence-building effect on depositors, in the sense of avoiding risks of self-fulfilling prophecies on bank runs.

The Jean Monnet principle is inter-temporal and applies at all times: “Europe is the sum of the solutions adopted to address the crises it is faced with.” The European clock is ticking down and the EU must take action at the June Council in two weeks’ time or at the latest at the December Summit, otherwise the European electorate will punish its politicians for their slow reflexes at the European elections in a year’s time, leading to a generalised crisis of confidence in the European Union. Over its long history, Europe has traditionally managed to find consensus on the burning issues facing it, even at the very last minute. As a true European myself, I only hope that this time will not be different!

Thank you very much for your attention.