Speech by Bank of Greece Deputy Governor John (Iannis) Mourmouras in London entitled: “Net Financial Assets in the Eurosystem: a comparative study”

05/04/2017 - Speeches

Net financial assets in the Eurosystem: a comparative study

by John (Iannis) Mourmouras,

Bank of Greece/Eurosystem

Former Deputy Finance Minister

Former Chief Economic Advisor to the Greek Prime Minister

Keynote speech delivered at the State Street Global Advisors (SSGA) roundtable

entitled “Policy rupture: Challenges and opportunities for public investors” organised by OMFIF

London, 5 April 2017

1. Introduction

Central banks hold assets worth approximately US $11.4 trillion (as at March 2015), with an additional US $6-7 trillion of assets held by sovereign funds and state investment agencies. The value of these assets has increased by more than 470% since 2000, when total reserve assets were worth about US $2 trillion. It is indicative that while nominal world GDP grew at an annual average rate of 6.2% since 2000, the total stock of global foreign reserves grew by 14.3% annually.

Central banks have certain financial assets and liabilities on their balance sheets that are not directly related to monetary policy, which are commonly referred to as ‘net financial assets’. Net financial assets arise as the result of management by central banks of their own investment including foreign exchange and gold reserves, government and non-banking sector deposit-taking, acting as a lender of last resort, etc.

Eurosystem national central banks implement the aforementioned tasks independently, provided that this does not impede the achievement of objectives and the implementation of the euro area’s single monetary policy. Similar to monetary policy instruments, changes in net financial assets affect the level of liquidity available to banks.

After various sovereign crises in the 1970s and 1980s, it became clear that reserves remained useful ―even necessary― for countries with floating exchange rates. There was a growing realisation that reserves conferred credibility and a heightened perception of financial stability. The Asian crisis of 1997-1998 highlighted two important points. First, the need for self-insurance: despite the theoretical backstop of official financial assistance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the terms under which assistance was offered were often unattractive or unpalatable. Second, in the event of a crisis, a foreign exchange buffer would be useful in terms of engaging in a conversation with the IMF. Preserving reserves was particularly relevant for Asian countries caught in the financial storm of 1997-1998. In contrast with orthodox theory, reserves were sometimes of more use when they were not utilised.

Total global foreign reserves are expected by late 2020 to return to their 2014 peak levels of around US $12 trillion, growing annually by around 2.6% between 2017 and 2020 (see Figure 1 above and Figure 2 below). 1

.png)

Looking forward, the investment tranche of global foreign reserves is estimated to reach US $1.94 trillion until 2020. As shown in Figures 3 and 4, around US $298 billion thereof is expected to be deployed either in equity or active fixed income strategies rather than passive fixed income products.

In my opinion, the major factor that encouraged growth in international central bank reserves is the evolving role of central banks. The latter have been given a role as the ultimate backstop for both financial markets and the economy; in the event of a potential crisis, foreign exchange reserves can become central bank resources. In April 2015, the IMF identified five reasons for holding reserves: to bolster confidence in the currency, to counter disorderly market conditions, to support monetary policy, to facilitate inter-generational transfers, and to influence exchange rates.2

.png)

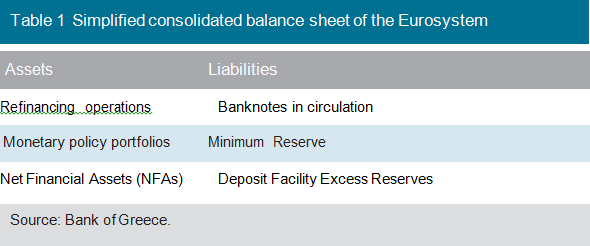

Excessive growth in net financial assets could lead to an overly limited manoeuvring room for the implementation of monetary policy. The Eurosystem therefore adopted the Agreement on Net Financial Assets (ANFA), which sets an upper limit on the total amount of net financial assets of all national central banks and the allocation of that amount between them. As shown in Table 1, the asset side of the consolidated Eurosystem balance sheet shows items that provide the banking sector with liquidity, while the positions on the liability side (with the exception of excess reserves) absorb liquidity from the banking sector. The NFA position is netted on the asset side of the consolidated Eurosystem balance sheet. The asset side can therefore be split into the NFA position and items relating to monetary policy operations (refinancing credit, and monetary policy portfolios). The liability side includes banknotes in circulation, the minimum reserve requirements of the commercial banks, and other liabilities from monetary policy operations (surplus reserves, deposit facility, and fixed-term deposits).

The Table below provides an example of the Eurosystem’s weekly financial statement as published on the ECB website, while Figure 5 shows the evolution of NFAs in the Eurosystem from 2002 to 2015.

.png)

.png)

As regards Eurosystem NFA composition, Figure 6 shows that gold and foreign currency reserves continue to make up the lion’s share of NFAs on the asset side. However, this share has followed a downward trend for some time in favour of securities such as money market instruments and bonds, including government bonds.

2. The Agreement on Net Financial Assets (ANFA)

The “Agreement on Net Financial Assets” (ANFA) between the European Central Bank and the National Central Banks (NCBs) is an essential component of the decentralised structure of the common currency and the single monetary policy in the euro area. It ensures compatibility between the single monetary policy and the national tasks of central banks. In the current environment of low inflation, in which the ECB operates in the vicinity of lower bound ―even negative― rates and still aims to maintain a certain level of excess liquidity, the ECB has a clear insight into the individual NFA transactions of the NCBs and, in my personal opinion, should continue to do so.

Upon the introduction of the euro, the ECB Governing Council also considered that if non-monetary policy portfolios, net of non-monetary policy liabilities, were to grow faster than the demand for liquidity for a protracted period of time, then this could put monetary policy at risk. The abovementioned Agreement on Net Financial Assets was established to manage and cap this growth.

The first ANFA was signed at the beginning of 2003, when monetary policy was implemented according to the standard market operations and the activities of the European System of Central Banks (ESCB) were carried out under a liquidity deficit. The agreement is revised every five years. Since the start of the global financial crisis in August 2007, central banks have taken on an increasingly active role as liquidity providers, and the Eurosystem altered the time-path of liquidity supply to the banking sector introducing unconventional monetary policy measures.

As a result, the ANFA was revised on 19 November 2014 and, more than a year later, on 5 February 2016, the agreement was published by the ECB for the first time.3 Up until the beginning of 2016, ANFA was a confidential document. At that time, there were voices arguing that central banks were possibly contravening the monetary financing prohibition with these asset purchases under ANFA. Following this debate, at the beginning of February 2016, the Agreement was released into the public domain. The NCBs took the unanimous decision that publishing the text along with an explanatory document would better serve their commitment to greater transparency, in line with the decision taken in 2014 to publish accounts of monetary policy meetings as well as the ECB’s decision in 2015 to publish the calendars of its Executive Board members. The next ANFA revision is expected in the end of 2019.

In a nutshell, prior to the crisis, ANFA protected the Eurosystem’s “liquidity deficit” imposing a limit on the amount of NFAs that national central banks could hold, while it currently ensures that excess liquidity does not surpass a level that the ECB Governing Council sees as appropriate for its monetary policy stance, as the banking system is now operating in a “liquidity surplus” environment.

To monitor compliance with the prohibition of monetary financing, the ESCB NCBs are required to inform the ECB about their assets and the ECB makes sure that the NCBs do not finance governments by buying their debt in the primary market. Moreover, pursuant to Articles 123 and 124 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), the ECB and the NCBs are not permitted to buy sovereign bonds on the primary market. As also clarified in Council Regulation (EC) No 3603/93,4 purchases of sovereign bonds on the secondary market may not be used to circumvent the objectives of this prohibition, and the acquisition of sovereign bonds on the secondary market may not, in practice, have the same effect as the direct acquisition of sovereign bonds on the primary market. The objective of the prohibition of monetary financing is, in particular, to encourage Member States to pursue a sound fiscal policy. The Governing Council of the ECB has determined rules for all investment operations of the NCBs to ensure that they do not contravene the monetary financing prohibition, thus the NCBs have to report their transactions on the secondary market. The ECB monitors compliance with the monetary financing prohibition and reports on the results of its monitoring in its annual report.

Should there ever be a violation of the prohibition, the ECB can ultimately take the NCB in question to the European Court of Justice. This has not happened so far. Moreover, due to the clearly defined NFA ceilings, the NCBs have very little scope to use NFA purchases of government bonds to permanently sustain more favourable market conditions in their own countries.

A final comment: as the ECB currently implements its expanded asset purchase programme, the composition of NFAs matters. For example, if individual monetary policy transactions and non-monetary policy transactions offset each other (e.g. one is a purchase of a security and another is a sale of the same security), this can send conflicting signals about the Eurosystem’s monetary policy intentions or reduce the effectiveness of monetary policy. Another example is central bank transactions in foreign currencies, which can impact exchange rates or be misinterpreted as exchange rate interventions. To ensure that these events do not interfere with monetary policy, the ECB has adopted measures that complement ANFA, including the ECB Guideline on Domestic Asset and Liability Management Operations by the National Central Banks,5> and the ECB decision to launch the public sector asset purchase programme (PSPP).6 While the former, for example, controls the net liquidity effects of NCBs’ operations, the latter limits, inter alia, the amount of a specific security eligible for the PSPP held in all portfolios of the Eurosystem NCBs.

3. NFAs in the euro area

In order to calibrate each NCBs’ NFAs, two parameters are set: the ceiling and the waivers.

3.1 The NFAs’ ceiling

First, the aggregate amount of available NFAs is defined and distributed to the NCBs in proportion to their shares in the ECB’s capital key. These distributed amounts are known as an NCB’s NFA entitlements.

Second, once the Eurosystem-wide ceiling for NFAs is set, the NCBs provide information regarding the extent to which they plan to utilise this leeway, as there may be both central banks that plan to hold more NFAs the following year than the entitlements distributed to them and those that plan to hold less than their entitlements. Up to certain limits, there is a temporary reallocation of unused leeway for holding NFAs to those NCBs that wish to hold disproportionately high levels of NFAs as measured by the ECB capital key. Should a central bank that has not made full use of its entitlement wish to use it in subsequent years, it is able to do so under ANFA’s calibration mechanism. If an NCB does not plan to use up its entitlement, ANFA foresees the temporary reallocation of the unused part to those NCBs that want a higher NFA ceiling. The NCBs’ NFAs must remain below their NFA ceilings on an annual average basis and the calibration is conducted also on an annual basis.

According to the current ANFA, the annual average NFAs per NCB in 2015 can be found in Table 3 below.

A deviation is justified if, for example, it is caused by international commitments to the IMF or by an NCB’s provision of Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) to its banking system (ELA is part of NFAs, as defined in ANFA). In such a case, the NCB must reduce its NFAs as soon as possible in order to comply with ANFA once again. For instance, as shown in Table 3 below, in the case of Greece, the value of NFAs in 2015 surged to €88 million due to an average ELA provision in that year of around €60 billion.

.png)

3.2 The waivers

The second parameter affecting the distribution of the maximum amount of NFAs in the Eurosystem concerns the waivers which define a minimum entitlement of NFAs that each NCB can hold. In other words, each NCB

has the right to hold a certain share of the maximum amount of Eurosystem NFAs, based on that NCB’s share in the ECB’s capital, with the amount corresponding to the waiver being that NCBs’ minimum entitlement (this may be higher than the amount calculated according to its share in the ECB’s capital).

There are three types of waivers:

a. The historical waiver (as specified in Annex III of ANFA) ensures that the NCBs do not have to reduce their NFAs below a level linked to their historical starting position.

b. The asset-specific waiver protects certain asset holdings (narrow items in Annex IV of ANFA) that cannot be sold easily by the NCB due to contractual restrictions or other constraints, e.g. a central bank’s gold reserves in view of the Central Bank Gold Agreement.7

c. The dynamic waiver adjusts the historical waiver of small NCBs over time in proportion to the growth or decline of Eurosystem maximum NFAs.

Only the highest of the three waivers applies. For example, on 1 January 2015 Lietuvos bankas joined the Eurosystem and became party to the ANFA with its historical waiver determined at €5,856 million.

The minimum amount of NFAs per NCB is presented in Table 4 below.

The following Figure shows the NFA portfolios across NCBs in the Eurosystem along with monetary policy operations:

Relative to the overall size of NCB balance sheets, due to APP holdings, NFA portfolios are modest, albeit not insignificant in some cases (notably in Italy, France and Spain).

.jpg)

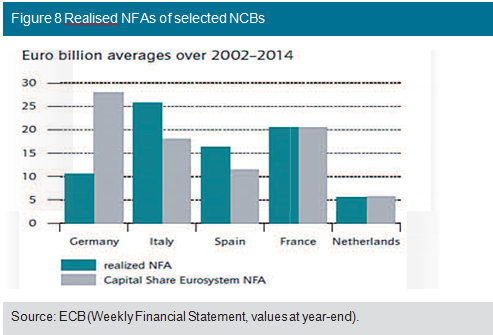

In practice, the realised NFAs may deviate from the allocation of NFA purchases, allocated according to the capital key, as shown in the following figure (Figure 4):

.png)

3.3 Four remarks

My own point of view can be summed up in the following four remarks.

Remark #1 (NCBs NFAs’ volumes & composition)

Composition: Each NCB’s NFA position within the Eurosystem has developed quite differently in terms of both volume and composition. The developments of NCBs’ balance sheets are quite heterogeneous. By and large, NFA positions are driven by gold and foreign reserves as well as euro-denominated securities. For the purpose of portfolio management, in addition to gold and currency reserves, the NCBs also hold a variety of other securities, including euro-denominated bonds and, to a limited extent, also shares. The various investment strategies partly reflect different preferences and owner structures, but, to a certain degree, also have historical justifications. For example, under the Central Bank Gold Agreement, various European central banks agreed to limit and coordinate any gold sales to keep market turbulences to a minimum.8 Central banks such as the Deutsche Bundesbank or De Nederlandsche Bank, which held considerable gold reserves before the introduction of the single currency, still hold major gold reserves. By contrast, countries such as Ireland, Italy, Spain, or Portugal, which had linked their domestic currencies to the Deutsche Mark (DM) under the European Monetary System, held substantial DM assets which were then converted to euros when the common currency was introduced. Consequently, the portfolio of euro-denominated securities on the balance sheets of these central banks was relatively high.

Volumes (classification): In terms of volume, we can classify Eurosystem NCBs into four categories:

I. NCBs with very low or even negative NFA positions such as Eesti Pank, the Central Bank of Luxembourg, the Bank of Slovenia which have very low levels of NFAs and Deutsche Bundesbank with negative NFAs. Of course, on the asset side of NFAs, the Deutsche Bundesbank’s position has masses of gold and foreign currency reserves.

II. NCBs with constant NFA positions such as De Nederlandsche Bank whose NFA position remained relatively steady over time. Another national bank with a stable NFA position is the Banque de France. In 2016, both central banks’ NFA positions dropped: as regards the former, from €22 billion to €17 billion, and as regards the Banque de France, from €106 billion to €80 billion.

III. NCBs with growing NFA positions such as the Banco de España’s NFA position, which has experienced considerable growth since 2004; it initially significantly expanded its euro-denominated securities, but has lately increasingly focused on building up its foreign currency reserves. From around €30 billion since 2001, having grown considerably since the beginning of 2004, its NFA position has tripled to around €80 billion. In 2016, Spain’s NFA position has declined to almost €60 billion. Also, Banca d’ Italia has the largest NFA position, which doubled from €50 billion in 2000 to more than €100 billion now, with the bulk of its financial portfolio comprising investment of its capital and pension fund, securities originating from the conversion of the State Treasury’s current account in 1993, and those acquired subsequently as investment of the balances arising from the State Treasury service provided by the Bank. More than 90% of the financial portfolio is invested in bonds, mainly Italian and other euro-area government securities, and the rest in equities, units of collective equity investment undertakings and exchange-traded funds (ETFs).9

IV. NCBs which include ELA in their NFA position such as the Central Bank of Ireland, the Bank of Greece, and the Bank of Cyprus. The development of the Central Bank of Ireland’s NFA position is particularly striking as it skyrocketed between 2009 and 2010 (more than €40 billion) when the Irish banking crisis reached its climax. The main reason for this upward movement up until 2013 was the provision of ELA. The Central Bank of Ireland extended a very large volume of Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) to Irish Bank Resolution Corporation (IBRC) and its predecessor banks during the crisis. At end-2015, the Central Bank of Ireland’s investment portfolio comprised assets worth €19 billion.10

In the case of the Bank of Greece, its NFA position has been affected by extensive ELA provision. More precisely, since August 2011, the Bank of Greece started providing liquidity to credit institutions through the ELA, which peaked at around €123 billion in November 2012. Increased central bank funding led to a sharp rise in its NFA position, including ELA, which is in accordance with the ANFA framework, but also to a significant drop in the Bank of Greece’s investment portfolios, to one-fifth of their pre-crisis value. After the success of the government bond buyback operation carried out in December 2012 and the upgrade of Greece’s sovereign rating, banks returned to Eurosystem facilities, which led to the rapid reduction in the amount of ELA since the beginning of 2014, before gradually declining down to zero in June 2014. Consequently, the Bank of Greece’s balance sheet started to be restored, as investment portfolios gradually rose, around the historical waiver of €22 billion. Unfortunately, in February 2015, Greek banks returned to borrowing from the ELA mechanism. As a result, the Bank of Greece’s NFA position excluding ELA was lowered to €7 billion, i.e. one third of its historical waiver of €22 billion in the end of 2016.

.png)

.png)

.png)

Remark #2 (QE)

From the above analysis, we can easily see that the largest part of the Eurosystem’s NCBs’ net financial assets are euro-denominated investment portfolios. Since March 2015 and the start of the ECB’s APP, asset management has become more challenging. The ECB manages a much bigger pool of assets, becoming a dominant creditor of governments, revealing the scarcity of high-quality euro area sovereign bonds; also, elevated demand has aggravated the shortage of supply. It is clear that QE affects all asset classes (including covered bonds, corporate debt, ABS, repos etc.) through the manipulation of risk-free rates.

Remark #3 (QE tapering)

Once the ECB’s QE is reversed due to tapering and as the normalisation of monetary policy unfolds, it is not unlikely that potential losses on these

securities could be perceived by the general public as bad management for all NCBs’ assets. We can only imagine the bad press that such losses resulting from their shrinking balance sheets could entail for central banks, on top of the criticism that the four major central banks are already subject to, as a result of their prolonged unconventional monetary policies. This could subject NCBs to parliamentary criticism and actions that could weaken their ability to conduct monetary policy in an independent manner.

Remark #4 (Volatility spikes)

In the past years, global financial assets have enjoyed unprecedented returns with only occasional bouts of minimal downward pressure. Upon the tapering of the ECB’s QE, this could also be associated with a steepening of the yield curve as expectations of low short-term rates are reversed and central banks reduce their holdings of long-term securities, triggering a rise in volatility at the long end of the yield curve. These effects would be more pronounced if the speed of interest rate adjustment were to exceed market expectations, just like last month’s rate rise by the Fed and the possibility of the ECB moving away from the negative deposit facility rate, as this is evident in the higher market expectations according to the latest Reuters poll.

4. The Bank of Greece’s NFAs: Composition, asset and risk management of the investment portfolios

Figure 10 below depicts the Bank of Greece’s monthly NFAs including ELA for 2016: the red line represents the NFAs ceiling (including ELA) approved by the ECB Governing Council. It should be pointed out that the amount of average NFAs including ELA for 2016 was €69.5 billion, much lower than the approved NFAs ceiling.

4.1 Principles of management

The objectives of the Bank of Greece’s financial portfolios management are, first of all, capital preservation and then income generation and, so both euro and foreign currency portfolios are invested in high-quality fixed

.png)

income assets. Not only capital preservation and income, but also managing the balance of risk, yield, and total return are our main challenges.

4.2 The Bank of Greece’s investment portfolio composition11

The Bank of Greece’s investment portfolios are denominated mainly in three currencies: euro, US dollar and pound sterling (see Figure below for the composition of the Bank of Greece's euro-denominated trading and hold-to-maturity portfolios as at end-2016).

The two foreign currency portfolios worth a total value of €2 billion are mainly invested in US and GBP treasury bills, government bonds, supranational fixed income products and deposits with official institutions such as other central banks and the Bank for International Settlements (BIS).

.png)

4.3 Risk management in the Bank of Greece's portfolio

As investment portfolios are an increasingly important component of the Bank’s assets, they are managed to obtain the maximum return for an acceptable level of risk. This means that the active portfolio management mandate for the Bank’s financial investment portfolio envisages the outperformance of its benchmark portfolio. Hence, the Bank of Greece has two benchmark portfolios, which are constructed and reviewed annually: one for the euro-denominated investment portfolio and one for the US dollar-denominated investment portfolio.

Furthermore, the Bank of Greece manages financial risks (interest rate, sovereign, market, credit, and liquidity risk) in an integrated manner and elaborates methods of assessment and risk control, on the level of its investment portfolios. Risk control of foreign exchange reserves and eurodenominated portfolios relies on a rigorous selection of counterparties and investment instruments; exposure to credit risk is mitigated by the definition of individual and asset class ceilings based on the creditworthiness of counterparties and issuers, as well as the liquidity of issues. These portfolios are also subject to operational risk control. To safeguard against legal risk, investment relationships with our counterparties are regulated by contracts drawn up based on standard models prepared by financial industry associations and in international usage, and adapted to take account of the Bank of Greece’s institutional role and functions.

4.4 Recent Bank of Greece asset management developments

The Bank of Greece has two Committees for the effective management of its financial portfolios: the Financial Asset Management Committee (FAMC) and the Risk Management Committee (RMC), both of which I chair.

My priorities over the past two years and a half as Chairman have been,

inter alia:

• The flexibility and the diversification in terms of foreign currencies. Besides our euro-denominated investment portfolio, we have also formed a US dollar-denominated investment portfolio.

• Following Brexit, the US election and the recent rate hike, we have started to hedge some of the duration exposure at portfolio level using Treasury futures, which allow us to access the asset class while mitigating the downside effect from rising rates. Government bonds and core fixed income offer very little protection against rising rates, which is why we focused on hedging for both euro-denominated and US dollar-denominated portfolios. As a result, during the last two years, our investment portfolios maintained relatively steady, positive results, outperforming our benchmark portfolios.

• Following the renminbi's recent inclusion in the IMF’s SDR basket,12 I have had personal talks with my Chinese counterpart, Mr. Yi Gang, and have now finalised the agreement with the People’s Bank of China to invest in Chinese government bonds through the secondary market or through the BIS CNY fund. I need not stress that China is important to my country through foreign direct investment (FDI), as this is the most crucial parameter for growth, which is very much needed to get Greece out of the woods.

The Bank of Greece’s RMC conducts independent assessments and controls the risks related to our investment portfolios through the approval of the appropriate benchmarks that fit with our conservative risk profile of a central bank’s mandate. Taking into account the current uncertain financial conditions, my priorities as Chair are: to correctly identify and label the risks, to determine suitable control measures and to ensure high-quality monitoring and adjustments. Of course, on top of that, we always make sure to have sufficient provisions for our activities, in terms of both monetary policy and investment portfolios.

5. The importance of a decentralised NFA management

Due to the diverging trends in the evolution of national NFA positions, and the lack of transparency, particularly that of the NCBs, there is a public debate on a more centralised asset management and a centralised Eurosystem investment portfolio. For instance, a recent paper by the influential German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin)13 argues that a more centralised structure of the Eurosystem’s central banks NFA management is needed in order to avoid misreading the motives behind the NCBs’ purchases for their NFAs as monetary financing. Instead, they propose the ability of NCBs with respect to financial assets could be more restricted through a more centralised central banking arrangement in Frankfurt, which, they argue, would improve the Eurosystem’s credibility and transparency. Views from academia and think-tanks are always welcome and important, and as a Professor myself, I support a two-way dialogue between scholars and central bankers, but at the end of the day, what matters is the official line of decision-makers. In the ECB Governing Council’s press conference in December 2015, President Draghi explained at great length that ANFA purchases are entirely a matter for national central banks which decide their investment policy in complete independence.14 And I have no reason whatsoever to doubt that his successor, whoever he/she is, will follow the same path.

On the other hand, there are economic and technical arguments against the centralisation of the NCBs’ reserves management. So let me present a few final thoughts in defence of maintaining the current status of NFA purchases with the National Central Banks and against the centralisation of NFA management at the ECB.

• A strong central bank balance sheet is important for a central bank’s credibility, all the more so at times of heightened uncertainty in financial markets. In other words, the efficient management of the NCBs’ financial assets enhances central bank credibility vis-à-vis both the markets and the general public to whom the central bank is accountable. Central banks can function even with negative net worth, but this undermines their financial independence and threatens policy effectiveness. Since credibility and reputational considerations are necessary conditions for the success of monetary policy, the central bank must be financially strong. The financial strength of an independent central bank must be commensurate with its policy tasks and the risks it faces. Losses or negative capital may raise doubts about the central bank’s ability to deliver on policy targets and expose it to political pressure. Central banking is not just limited to its technical nature, but is also a public good and, in that respect, it has political economy aspects. Hence, the decentralised management of NCBs’ own reserves helps to achieve and preserve their economic independence vis-à-vis both their national governments and Frankfurt-based personnel.

• Given the substantial value of these reserves, a common reserves management is not necessarily optimal. The risks of pooling from such a centralised portfolio structure with the ECB are proportionately shared if each NCB manages its own reserves. This is also in line with the principles of ECB’s asset purchase programme (APP), as purchases of securities are subject to limited risk-sharing. In addition, and on a more permanent basis, the very management of the ECB’s own foreign reserves takes place in a decentralised manner.

In short, in order for National Central Banks to remain financially independent institutions that implement Eurosystem monetary policy and fulfil national tasks, the decentralised nature of NFA management should remain intact.

1See State Street Global Advisors (2017), “How do Central Banks Invest A glance at their Investment Tranche”, p. 2.

2See IMF Policy Paper (2013), “Assessing Reserve Adequacy Further Considerations and Reserve Asset Adequacy -Specific Proposals”, 15 November 2013.

3Available on the ECB’s website, at: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/ecb/legal/pdf/ en_anfa_agreement_19nov2014_f_sign.pdf.

4Council Regulation (EC) No 3603/93 of 13 December 1993 specifying definitions for the application of the prohibitions referred to in Articles 104 and 104b (1) of the Treaty, OJ L 332, 31/12/1993 pp. 1-3.

5Guideline of the European Central Bank of 20 February 2014 on domestic asset and lia- bility management operations by the national central banks (ECB/2014/9)

6Decision (EU) 2015/774 of the European Central Bank of 4 March 2015 on a secondary markets public sector asset purchase programme (ECB/2015/10).

7On 19 May 2014, the European Central Bank and 20 other European central banks announced the signing of the fourth Central Bank Gold Agreement. This agreement entered into force on 27 September 2014 and will last for five years. Further information is available on the World Gold Council’s website, at: http://www.gold.org/news-and-events/press- releases/ central-bank-gold-agreement-renewal-demonstrates-continued-commitment.

8The first Central Bank Gold Agreement was signed in 1999. There have since been three further agreements, in 2004, 2009 and 2014. See also previous footnote.

9Banca d’ Italia press release, “Clarifications on assets held by NCBs for non-monetary purposes”, December 2015.

10Central Bank of Ireland press release, “Questions and Answers on ANFA”, February 2016.

11Based on data published in the Bank of Greece’s Annual Report, December 2016.

12Following a decision by the IMF’s Executive Board agreed to change the SDR’s basket currency composition in November 2015, the Chinese renminbi (RMB) was added on 1 November 2016 to the basket of currencies that make up the IMF’s Special Drawing Right, or SDR, an international reserve asset created by the IMF in 1969 to supplement its member countries’ official reserves.

13See Philipp König and Kerstin Bernoth (2016), “The Eurosystem’s agreement on net financial assets: covert monetary financing or legitimate portfolio management?”, DIW Economic Bulletin, Volume 6, 23 March 2016.

14See Introductory statement to the press conference of Mario Draghi, President of the ECB, and Vítor Constâncio, Vice-President of the ECB, Frankfurt am Main, 3 December 2015.