Article by Bank of Greece Deputy Governor John (Iannis) Mourmouras entitled: “Revisiting central bank independence”

05/01/2017 - Articles & Interviews

“Central banks in an unconventional era -

Monetary independence supports global economy”

Article by

Professor John (Iannis) Mourmouras

Deputy Governor, Bank of Greece

Former Deputy Finance Minister

published in the January 2017 issue of the OMFIF Bulletin

The intellectual roots of central bank independence (or CBI) can be traced back to the rational expectations revolution, pioneered by the Chicago School in the 1970s. This put forward the idea that people base choices on their rational outlook, past experiences and available information. Rational expectations played a pivotal role in breaking the intellectual deadlock with addressing the ‘stagflation’ phenomenon of the 1970s, when high inflation was combined with high unemployment and slow growth.

Under discretionary monetary policy in a rational expectations framework, the interaction of private agents with the government generates an inflation bias, without any sustainable output gains. This bias increases with governments’ displeasure at the size of the output gap. As a result of this perceived bias, governments and central banks around the world moved to conduct monetary policy with a credible commitment to low inflation, anchoring inflation expectations to equally low levels.

Monetary policy in the post-crisis period

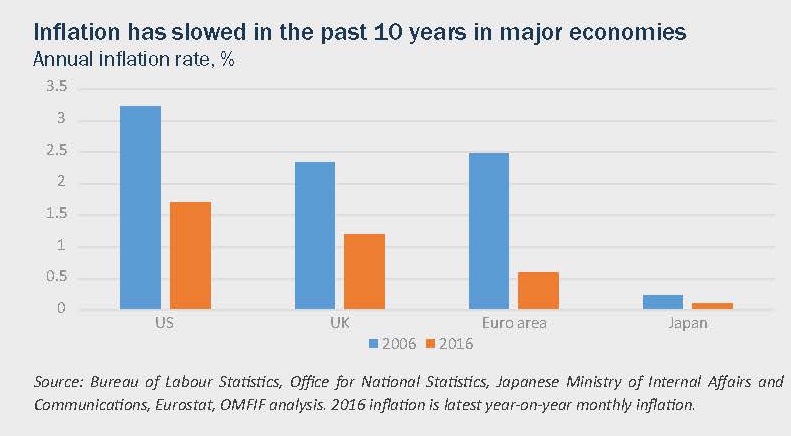

The financial crisis of 2008 and the ensuing European sovereign debt crisis have fundamentally changed the operational framework of independent central banks. Central banks have been given new macroprudential tasks, such as the supervision of systemic banks in economic and monetary union, conducted by the European Central Bank since 2014. Another important change is that in the post-crisis era price stability is about preventing deflation, rather than halting excessive inflation. As a result, all major central banks have employed unconventional monetary policy tools in recent years. These include the provision of emergency liquidity and credit support to banks and extending the definition of assets accepted as eligible collateral when providing loans on a short- or medium-term basis. To help raise inflation to targeted levels, central banks have turned to negative base rates and quantitative easing, considerably expanding central bank balance sheets. Since 2008 the Fed’s balance sheet has more than doubled, while the Bank of England’s has tripled. The ECB’s balance sheet has grown 66% since its QE programme started in 2015.

Central bank challenges for independence

The legacy of the 2008 crisis and subsequent low inflation have brought challenges for central bank independence. First, external parties have questioned the independence of central bank policy instruments. Second, even if these policies are not formally challenged, they may be less likely to achieve their objectives because of the altered conditions. Such questioning is arguably aimed at the wrong target. I believe criticism should not be directed against the very concept of independence, but rather against the current economic mix of ultra-loose monetary policy with tight fiscal policy.

Monetary policy naturally interacts with fiscal, structural and financial policies. The separate authorities that conduct these policies may be formally independent, but they are also interdependent. The risk of such interdependence is that, if one independent policy authority does not take appropriate action to meet its mandated objectives, the other authorities may be obliged to overreact to persistent shocks to meet their own objectives. This may result in a regime of ‘weak dominance’ of other policies over monetary policy, effectively destabilising the regime of monetary dominance that central bank independence is meant to establish.

When interest rates are kept negative for too long, both the redistribution effects of monetary policy and the perceived degree of success of meeting the mandated objectives become more pronounced. This leads to greater demands for scrutiny of central bank independence. Concerns naturally arise about whether a monetary authority with an extended mandate of objectives can operate transparently and with appropriate accountability in a democratic political and economic system.

“The independence of central banks may be scrutinised due to concerns about whether a monetary authority with an extended mandate can operate transparently and with an appropriate degree of accountability”

An independent central bank subject to checks and balances and democratic accountability needs public backing. When negative rates persist, central banks almost inevitably lose major parts of the necessary broad constituency of support. There is still a strong overriding need for Independent central banks focused on price stability, capable of creating policy room for necessary structural adjustments, appropriate fiscal policies and macroprudential stability. All the theoretical and empirical arguments point in this direction: this approach offers the most promising path for the ultimate objective of restoring normal growth conditions and creating jobs. Controversy about the means and goals of central banking independence is no reason why the world should water down a concept that has served the global economy well over 40 years.