Speech by the Governor of the Bank of Greece Yannis Stournaras at Delphi Economic Forum II: Greece and the euro area going forward

04/03/2017 - Speeches

Ladies and Gentlemen,

It gives me great pleasure to be here today in Delphi to address an audience of such distinguished people, from academics to those involved in policy-making at the highest levels. In my speech, I want to focus on two main themes. First, Greece. What progress has been made? Where do we stand? What are the prospects for the economy not just over the short-to-medium term but also in the long term? Second, I want to say a few remarks about the euro area. In particular I want to discuss the steps taken by the ECB in order to lessen the impact of the crisis in the euro area, including changes to governance in EMU. However, looking forward, the challenge facing the euro area is to make it more resilient to shocks and I will outline how, in my view, resilience can be enhanced.

Greece: the current juncture

The Greek economy is at a turning point. Growth turned positive in the second quarter of 2016 and, contrary to initial forecasts, it turned out positive for the year as a whole. Some recent softening of economic indicators can be put down to uncertainty in the face of delays in closing the second review of the programme. Hopefully this is now moving forward. A rapid closure of the review will help the economy to build on the 2016 over-performance and move quickly to a faster growth path.

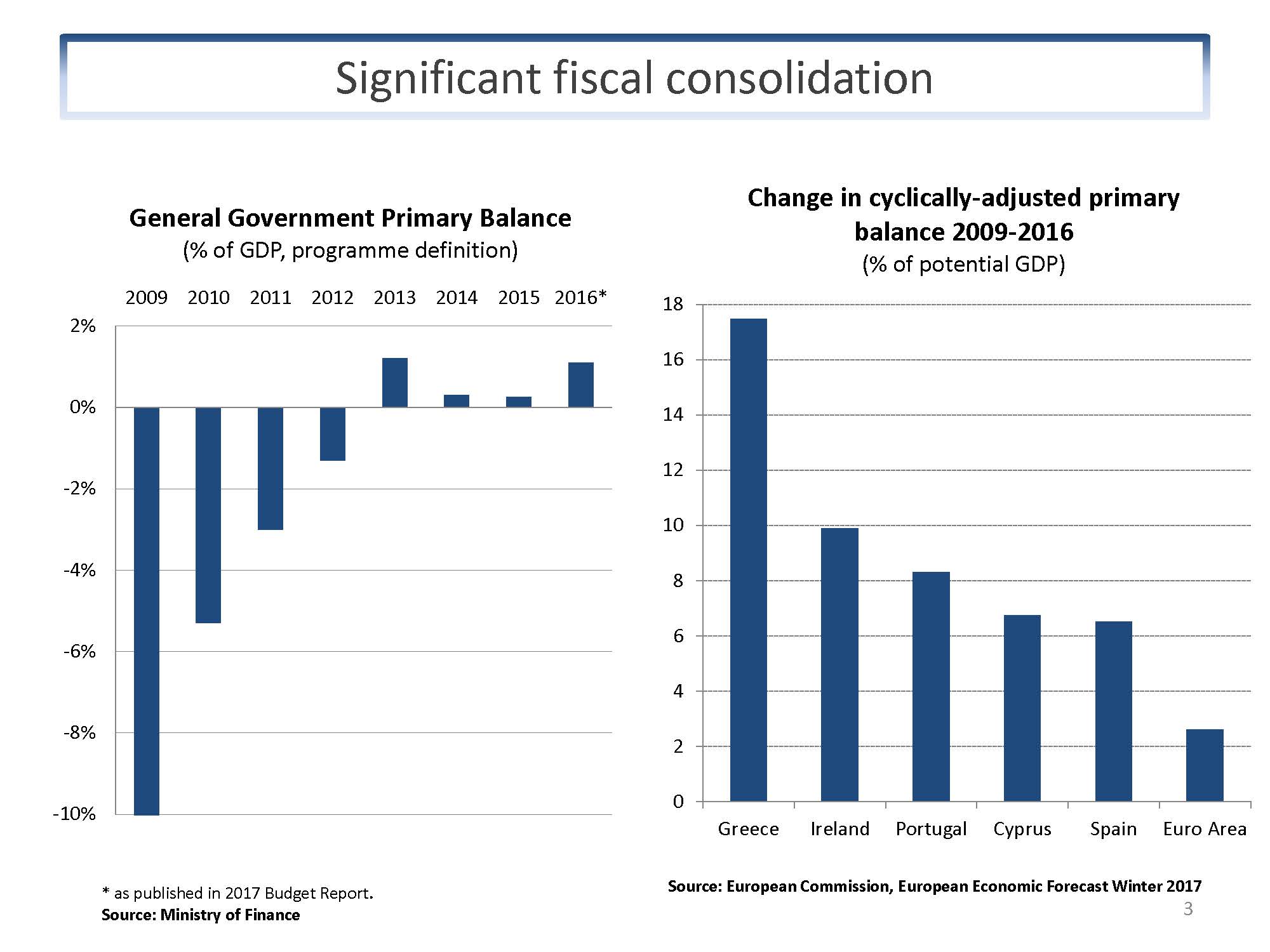

It is important to emphasise just how far Greece has come since the onset of the crisis in 2009. Adjustment, particularly of the flow disequilibria which characterized the Greek economy on the eve of the crisis, has been considerable. The twin deficits have been eliminated. Between 2009 and 2016, the general government deficit is estimated to have shrunk by approximately 14 percentage points of GDP. The primary balance according to the programme definition is expected to have improved by 12 percentage points and is currently projected to reach a surplus of around 2 percent of GDP in 2016, against a target of 0.5 percent of GDP. Adjusting for the effect of the business cycle, the improvement in the primary balance comes in at more than 17 percentage points of potential GDP. This represents one of the largest fiscal adjustments ever undertaken.

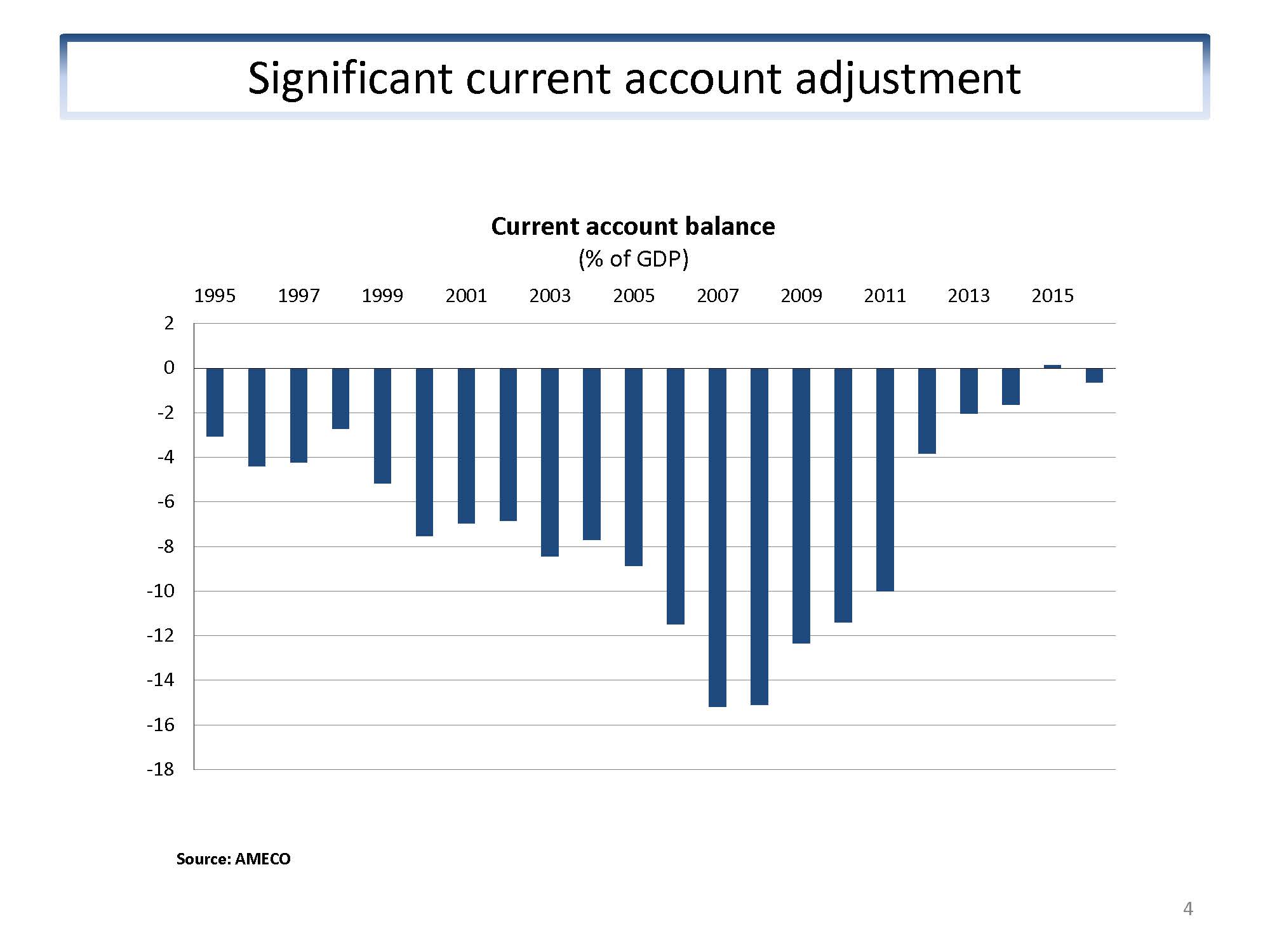

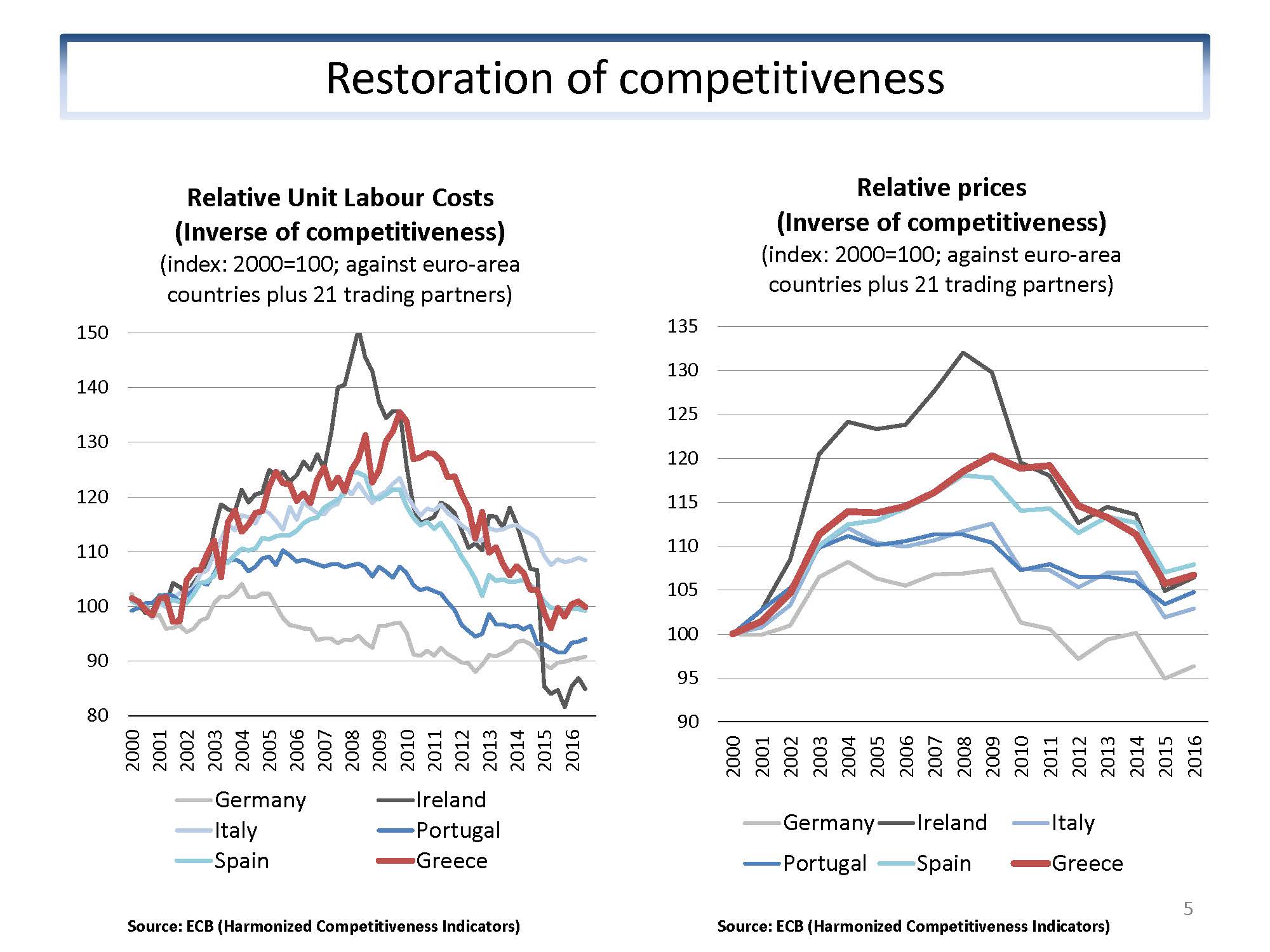

The current account deficit as a percentage of GDP has fallen by 15 percentage points. For the last two years the current account has effectively been in balance. Labour cost competitiveness has been fully restored and price competitiveness is almost back at its level of 2000 and can be expected to continue to improve with the implementation of further product market reforms that raise competition in various sectors of the economy.

At the same time, sweeping structural reforms have been implemented covering the pension system, the health system, labour markets, product markets, the business environment, public administration, the tax system and the framework in which fiscal policy is conducted. The privatization programme is on-going, though there is a pressing need to speed up the process and actively attract foreign investment. Foreign direct investment would provide an additional boost to growth, not least by financing new investment.

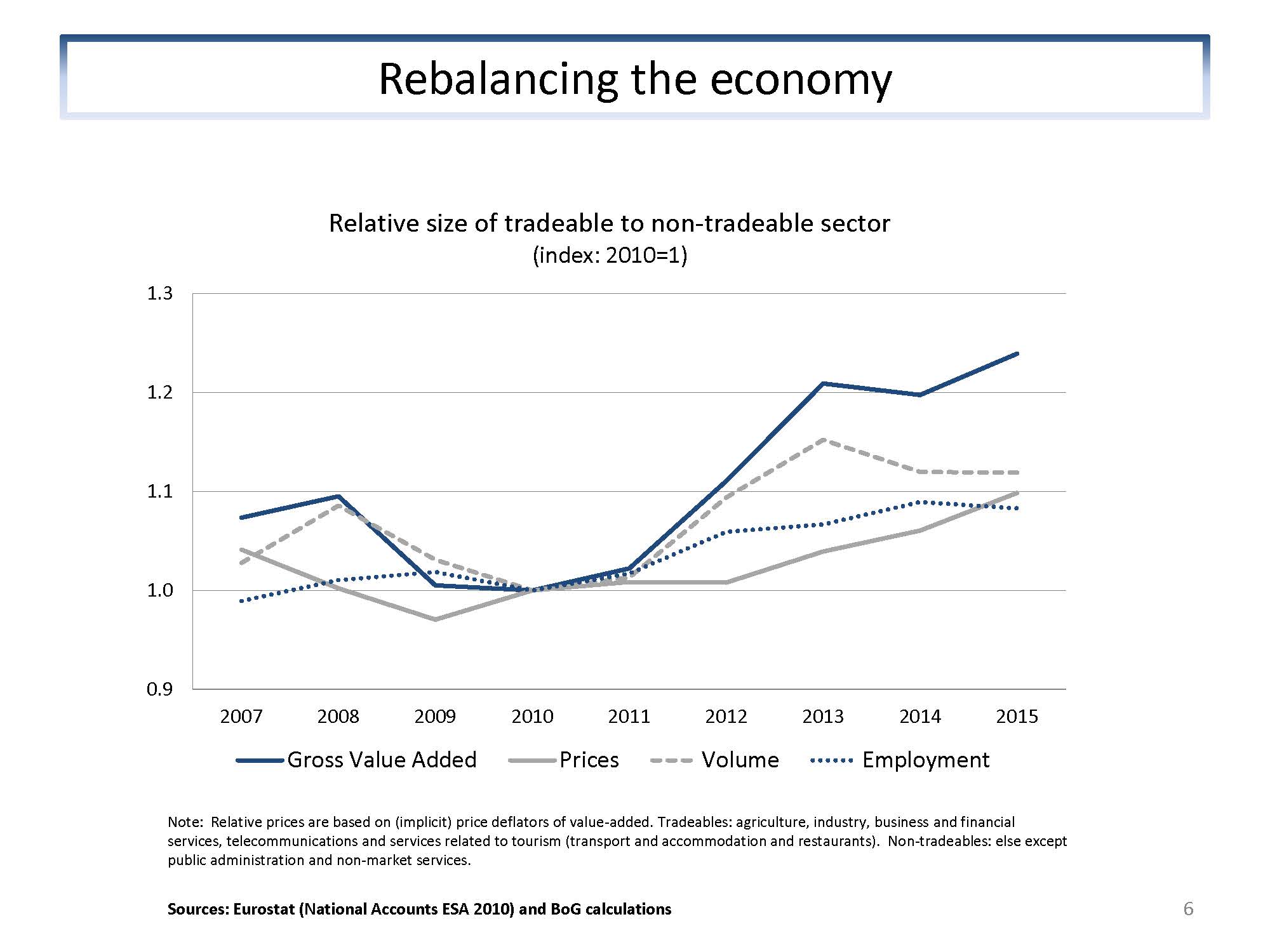

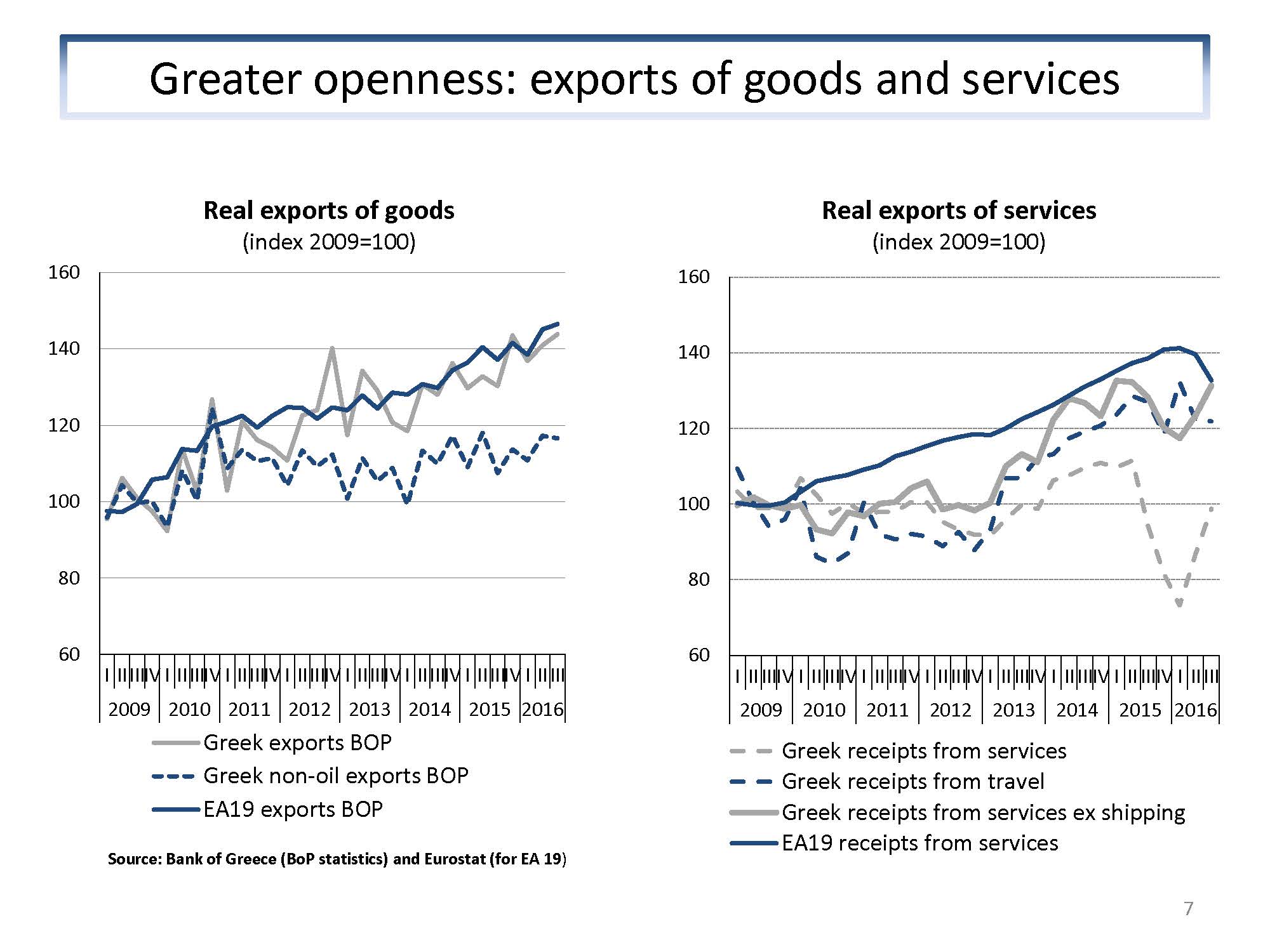

There is evidence that the economy has been undergoing a rebalancing towards the tradables sector. The size of the tradables sector relative to that of nontradables has been increasing since 2010 – whether measured in terms of gross value added, employment or the volume of output. The ratio of tradables-to-nontradables prices has also risen, encouraging resources in the economy to move into tradables. This rebalancing has been reflected in a rise in the openness of the economy. Exports of goods have also grown in line with our euro area partners. Underperformance in services is related to tourism and shipping. Tourism underperformed in 2011-2012 as a consequence of uncertainty, but has since seen a sharp rise. Shipping underperformed largely due to global factors and, latterly, the imposition of capital controls.

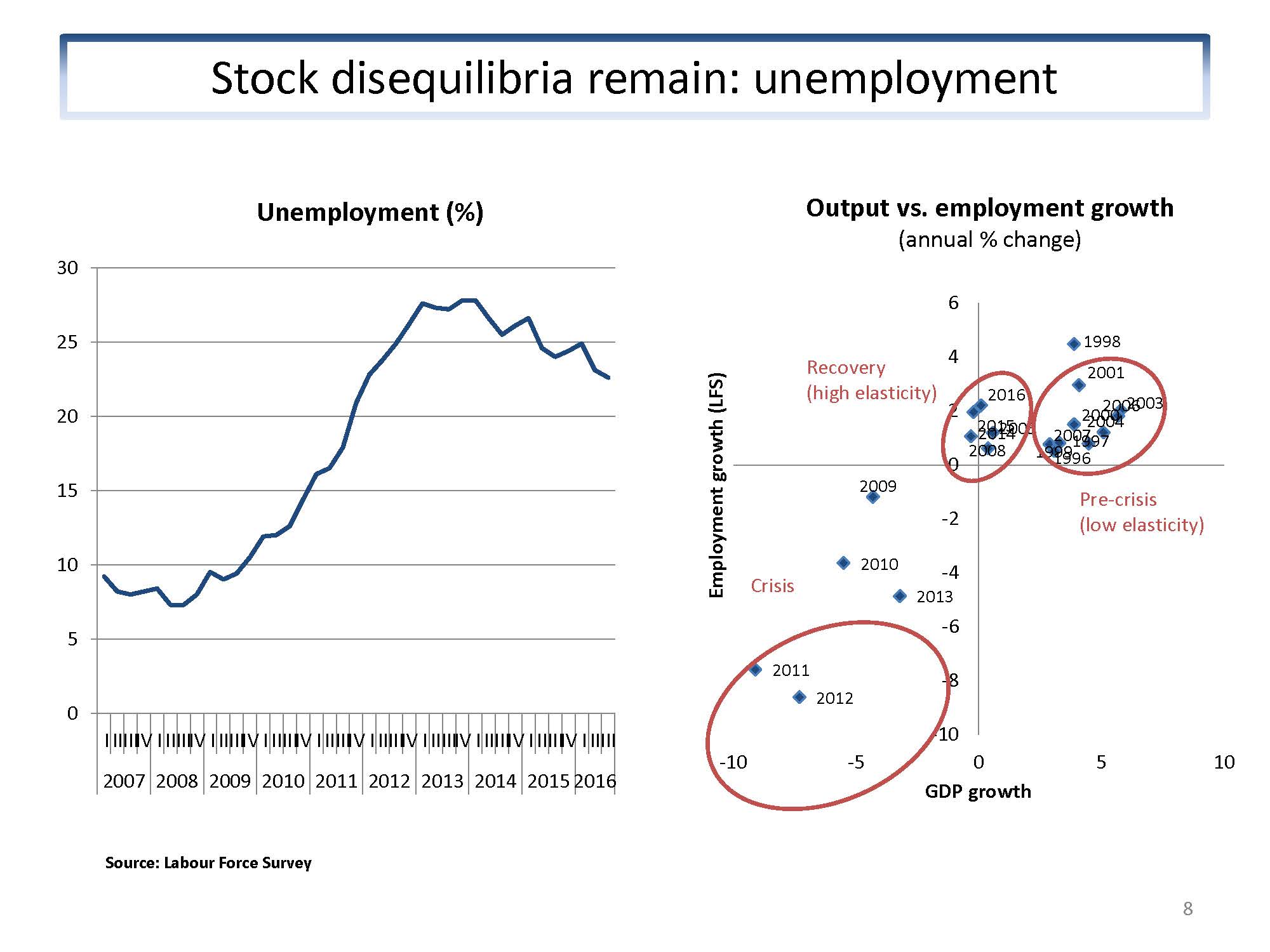

In spite of these positive developments, I do not wish to underplay the fact that considerable stock disequilibria remain. Unemployment, though falling, remains high. The labour market reforms already enacted have contributed significantly to moving us into a recovery stage where there is a high elasticity between GDP growth and employment growth. Indeed, even in 2015, when growth was negative, positive employment growth was observed. However, the composition of unemployment, coupled with the high percentage of young people “Not in Education, Employment or Training”, highlight a need to focus on life-long learning and a better matching of skills. The active employment policies and the vocational training programmes of the Greek Manpower Employment Organisation (OAED) can contribute in this direction, with appropriate planning and targeting and the optimal utilisation of available, mostly EU, funds.

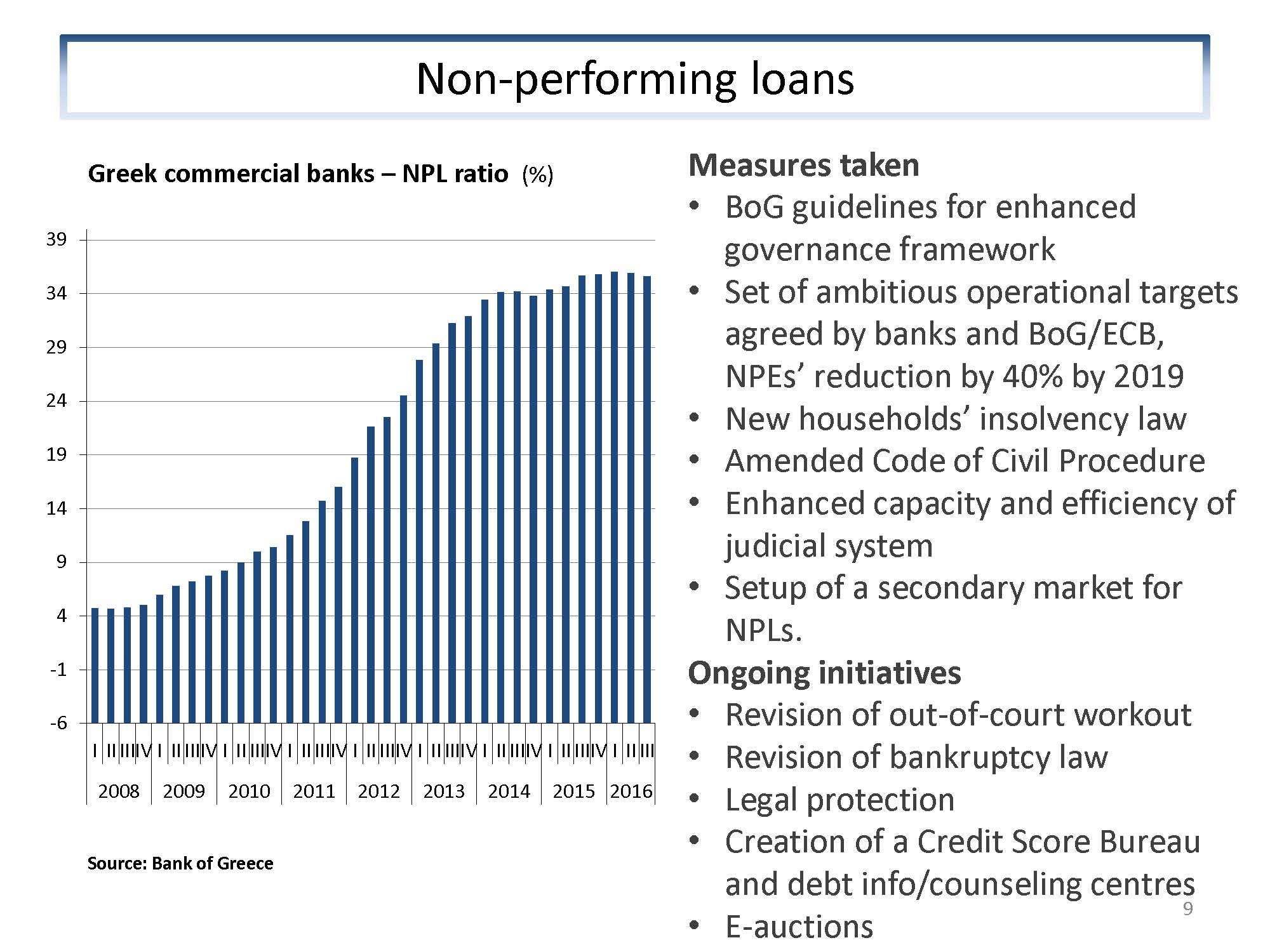

Non-performing loans remain high and an efficient management of those loans is of utmost importance for the banking sector and economic growth. Many initiatives have already been taken, such as, the Bank’s Guidelines for an enhanced governance framework and the adoption of operational targets agreed by the banks and the Bank of Greece/ECB to reduce non-performing exposures by 40% by 2019. On-going initiatives include the revision of the out-of-court workout and bankruptcy law.

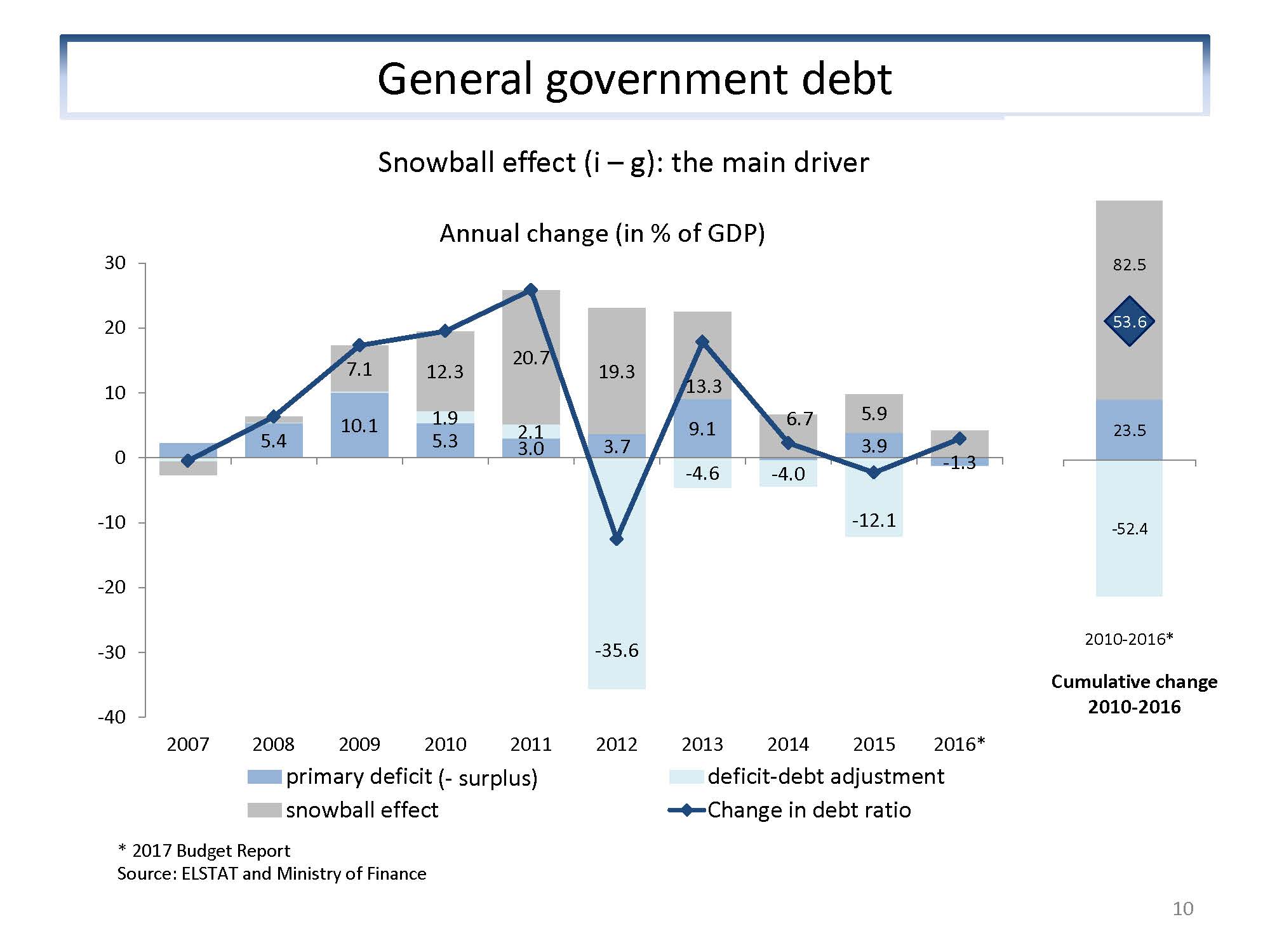

Finally, the ratio of general government debt to GDP is still high. In 2008 that ratio stood at around 110%. It is now around 180%. The debt path has been strongly affected by the so-called snowball effect – that arises from a combination of interest rates on debt being much higher than growth. Indeed, from 2010 to 2016, the snowball effect is estimated at some 82% of GDP. But whatever the causes of its rise, it is crucial that it is placed on a sustainable path.

Prospects for the Greek economy

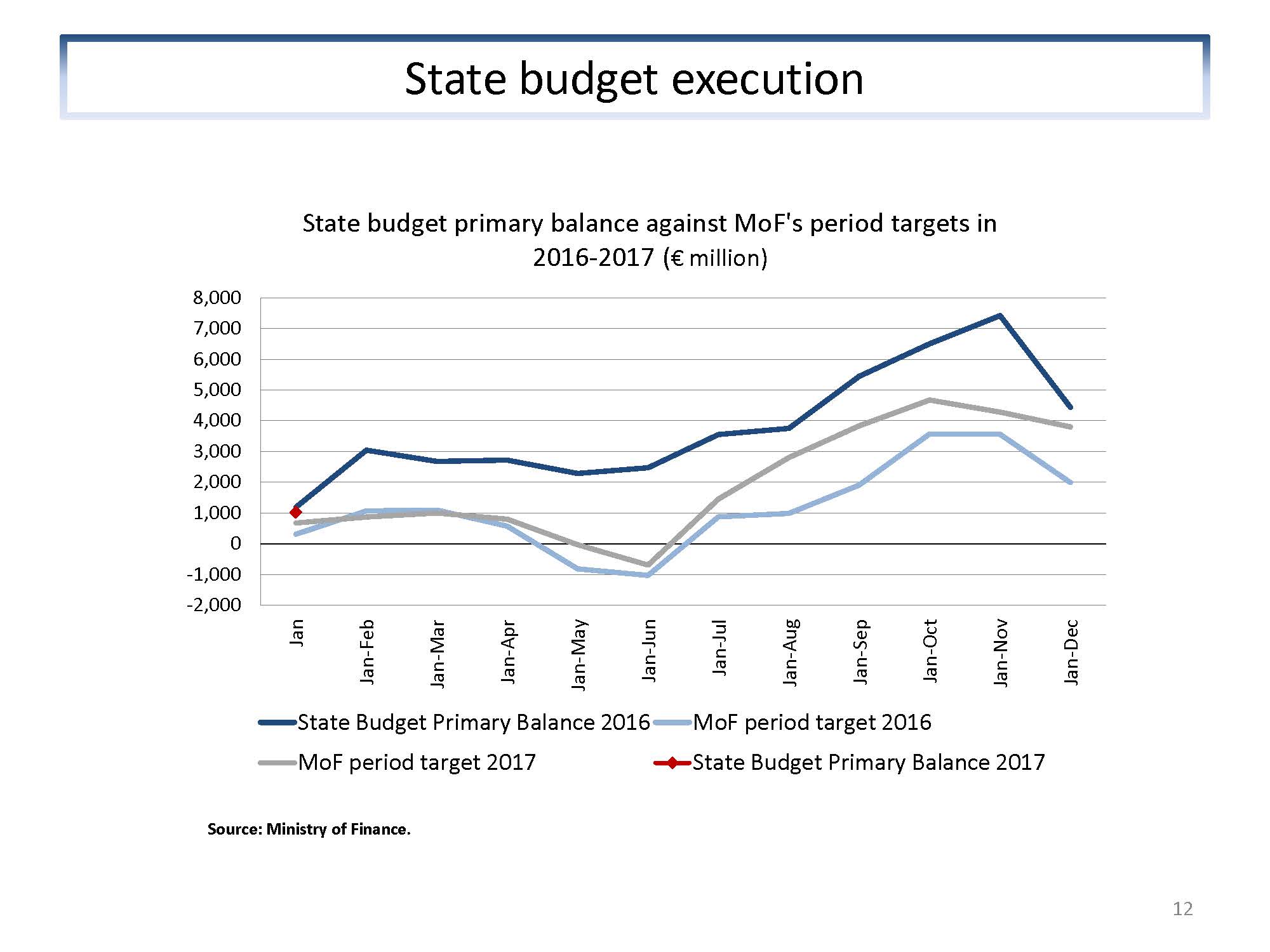

What are the prospects for the Greek economy? Strong positive growth rates are expected over the short and medium term as the output gap closes. Consumption is expected to continue to rebound, driven by employment growth. Investment and exports are expected to increase as confidence is restored and financial conditions improve. At the same time, the fiscal outlook is promising. Over-performance in 2016 will be carried over into 2017. Indeed, we have already seen tax revenue over-performance in January of this year. Finally, the clearance of arrears accelerated in the second half of 2016 injecting much needed liquidity into the real economy.

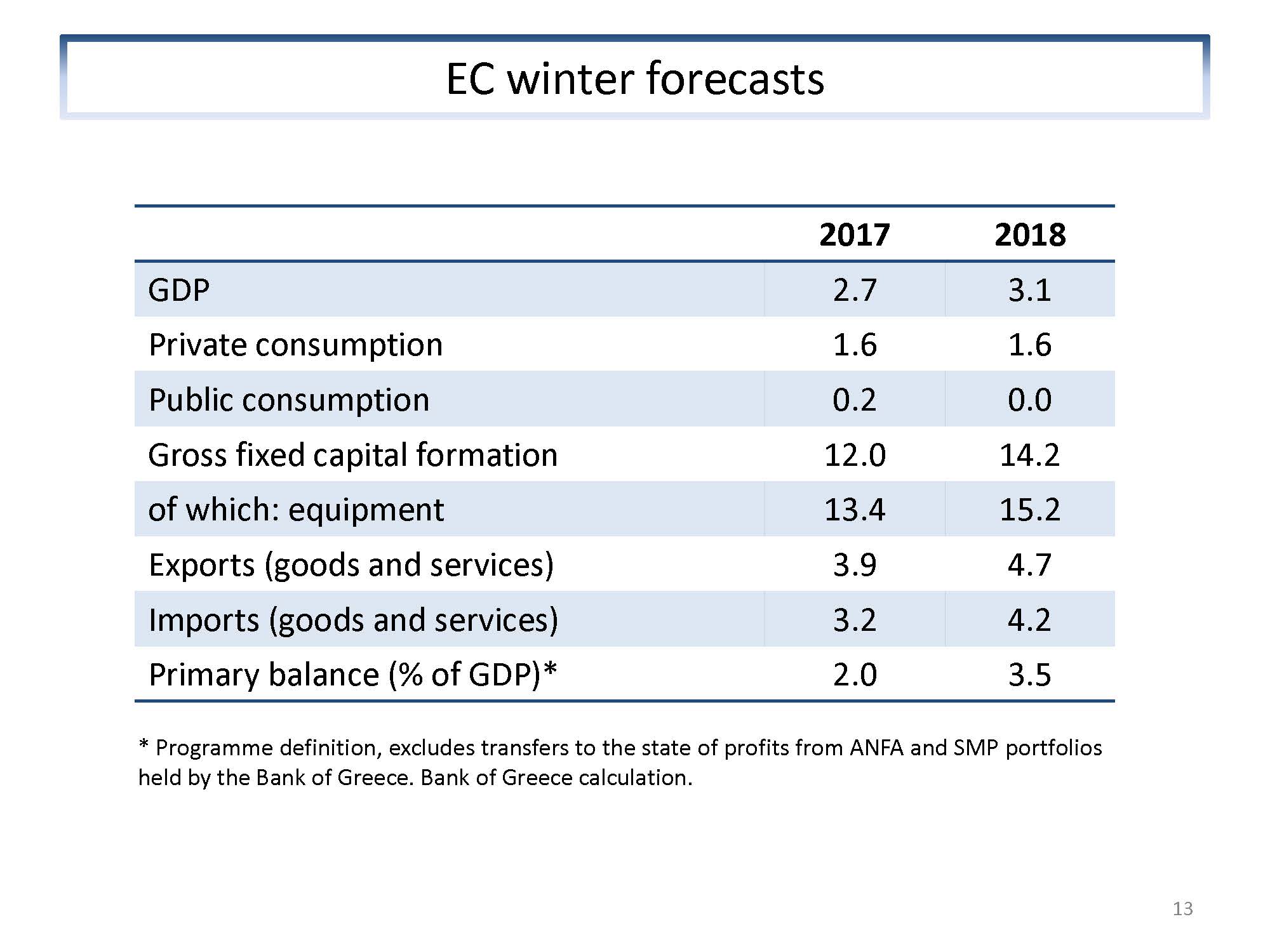

The recently published Winter Forecasts by the European Commission are in line with the above story. Growth is expected to accelerate to 2.7% in 2017 and to 3.1% in 2018, supported by consumption growth of 1.6% in both years, two-digit growth in gross fixed capital formation and export growth of around 4% in 2017, rising to almost 5% in 2018.

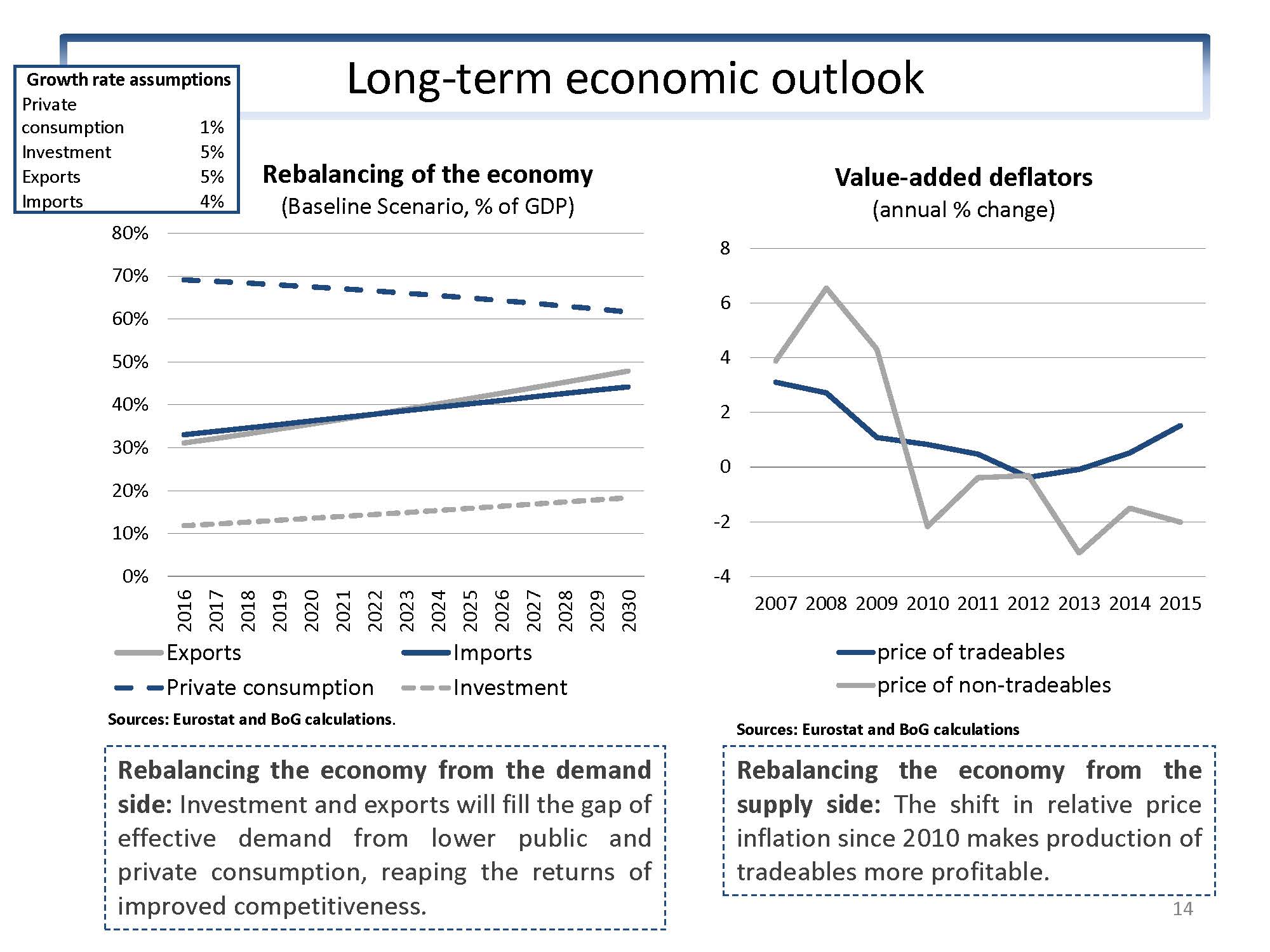

What about the longer-term economic outlook? Labour force dynamics will support potential growth in the medium term. But in the long run, growth will come from increased productivity. In this respect, structural reforms will unleash the growth potential of the Greek economy, with the OECD estimating that the impact of implemented and planned reforms over 10 years would be to raise output by 13.4 per cent. Analysis done by my colleagues in the Bank provides a baseline scenario for a rebalancing of the economy from the demand side that has the following characteristics. Consumption as a percentage of GDP declines by around 10 percentage points, moving closer to the euro area average. Investment and exports fill the gap in domestic demand. From the supply-side, I have already noted the rebalancing towards tradables, supported by the shift in relative price inflation since 2010.

The Bank of Greece has recently made a number of proposals in the area of fiscal policy and government debt which would go a long way to securing the performance outlined above and reducing these stock imbalances.

Firstly, there is the issue of the fiscal mix. To a significant extent, the overperformance of fiscal policy relative to target in 2016 was due to increases in tax rates – both indirect and direct tax rates along with social security contribution rates. This emphasis on taxation needs to be reduced since it stifles growth, increases unpaid debts of the private sector towards the public sector and encourages tax evasion and undeclared employment. Rather emphasis needs to be placed on restraining and restructuring non-productive spending and making more effective and efficient use of the public sector’s assets, especially land.

Second, there is the issue of the fiscal target. According to estimates from the Bank of Greece, a lowering of the general government primary surplus target from 2021 onwards to 2 per cent of GDP, from the 3.5 per cent that is envisaged now, would be consistent with debt sustainability if combined with some mild debt relief measures and structural reforms to raise potential growth. The easing of the primary surplus targets, together with the implementation of the agreed structural reforms, would put the necessary conditions in place for a gradual lowering of tax rates, with positive multiplier effects on economic growth.

Finally, there is the issue of what debt relief measures. The short-term measures decided at the Eurogroup meeting of the 5th of December last year are a positive step and are expected to reduce public debt as a ratio of GDP by 20 percentage points by 2060. At the same time they also reduce the annual gross financing needs of the general government by around 5 percentage points of GDP.

However, to ensure the sustainability of the debt going forward, additional medium-term measures are also necessary. When the debt-to-GDP ratio is above 100%, measures that reduce interest payments on debt can improve the ratio quicker than a rise in the primary balance. For example, with a debt-to-GDP ratio of 180%, a 1 percentage point reduction in the average interest rate on debt will reduce the ratio of debt to GDP by 1.8 percentage points. By contrast, a rise in the primary surplus as a percentage of GDP by 1 percentage point lowers the debt-to-GDP ratio by only 1 percentage point (assuming that the fiscal multiplier is 0 which, as we well know, it is not). A similar effect to lowering the interest rate can be achieved through a rise in nominal growth.

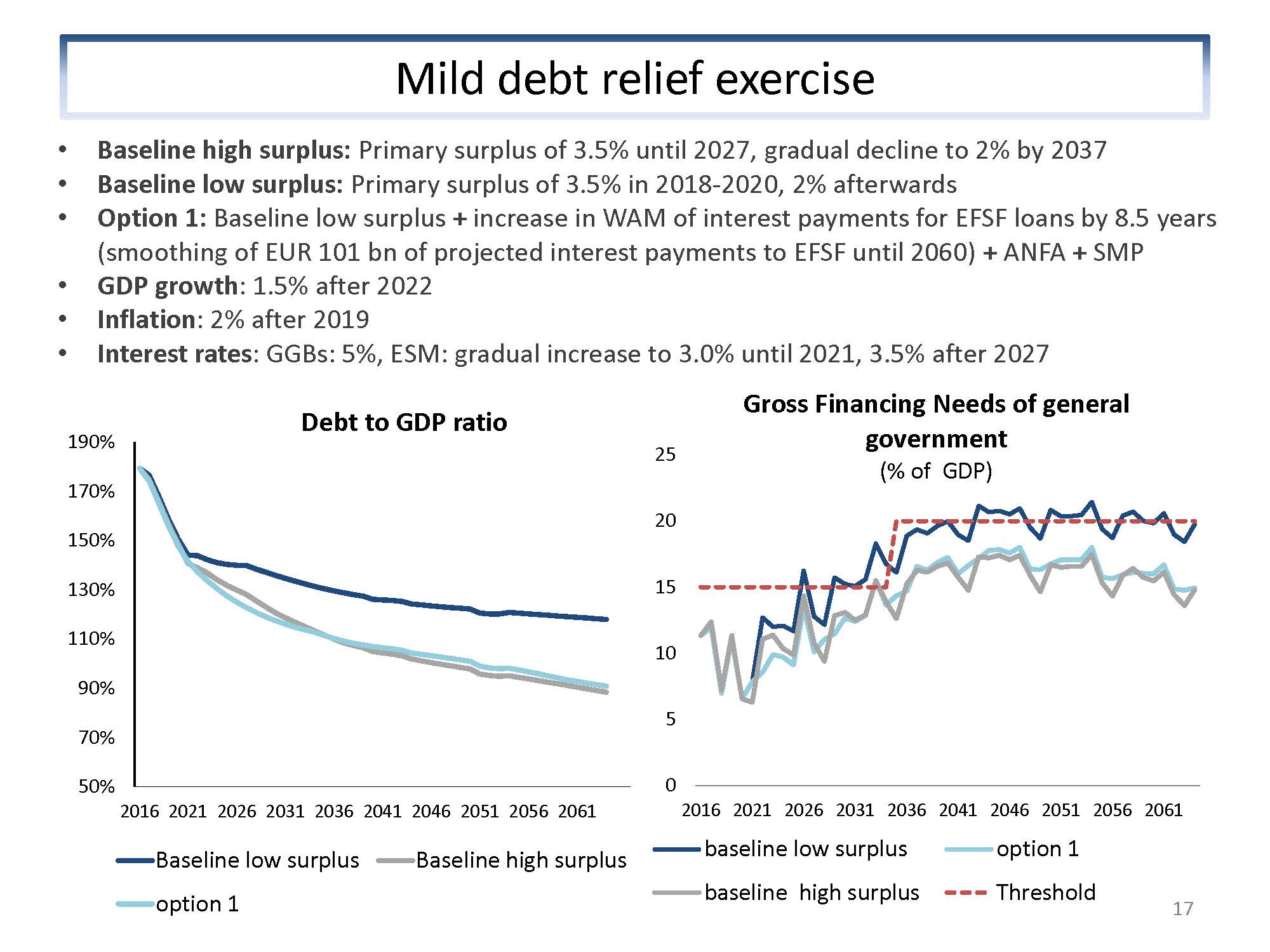

For debt to be sustainable, it is important to look at the gross financing needs of the general government. The Eurogroup agreement of the 24th May last year set the goal for gross financing needs of the government to be below 15 per cent of GDP in the medium term and below 20 per cent over the long term. With a primary surplus goal of 2 per cent, gross financing needs are higher than they would be if the primary surplus were held at 3.5 per cent.

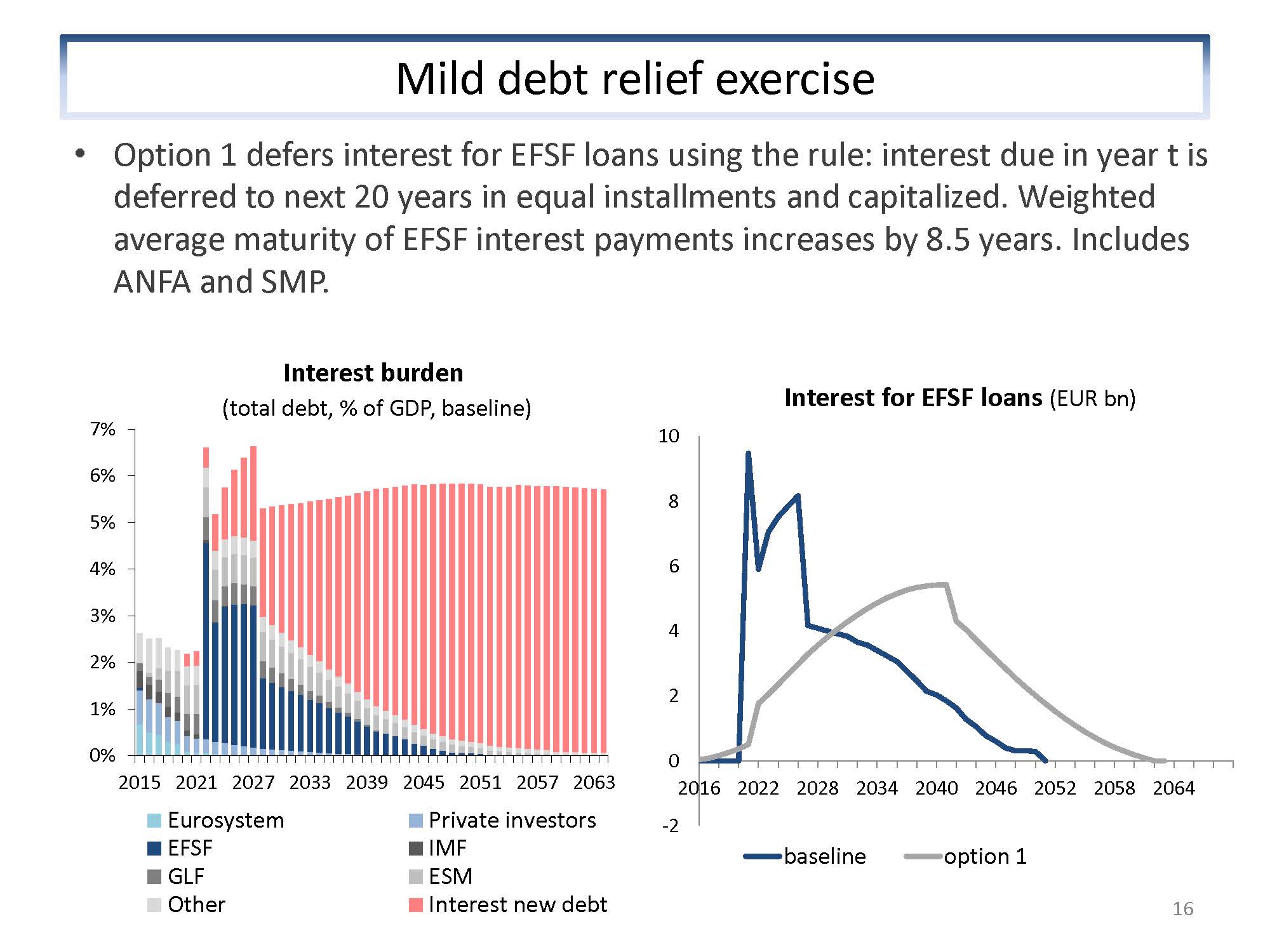

However, mild debt relief could reduce them and keep them within the limits set by the Eurogroup. The interest burden is low until 2021 but increases substantially thereafter because of payments of deferred interest on the EFSF loans and interest on new debt issued in financial markets. An exercise done at the Bank looks at the impact of smoothing interest payments for EFSF loans. Looking at the right-hand-side diagram on the slide, the exercise entails that interest payments are smoothed, as in option 1, instead of remaining as they are now (the baseline scenario). What does such an exercise imply for the path of debt and gross financing needs? The baseline high surplus scenario assumes primary surpluses of 3.5 per cent of GDP until 2027 and a gradual decline to 2 per cent by 2037. The baseline low surplus assumes only three years of primary surpluses of 3.5 per cent of GDP and 2 per cent thereafter. Clearly the lower surpluses imply a smaller fall in the debt-to-GDP ratio and higher gross financing needs. However, the smoothing of interest can mimic the baseline high surplus case both on the path of the debt-to-GDP ratio and in terms of gross financing needs. On the basis of the definition of sustainability agreed by the Eurogroup, the debt is sustainable since gross financing needs remain under 15 per cent of GDP in the medium term and under 20 per cent in the long term.

This exercise is indicative of how even a mild debt relief can have significant effects on the debt profile. Of course, were the interest smoothing accompanied by higher growth, as a consequence of lower primary surpluses, then the debt-to-GDP profile and gross financing needs would be even more favourable. Alternatively if interest rate smoothing were to occur and the costs shared equally between Greece and the ESM, this would also lead to more favorable outcomes.

The euro area: steps taken to address the crisis and to strengthen the governance of EMU

Let me now turn to the issue of the euro area and the steps that have been taken to address the sovereign debt crisis.

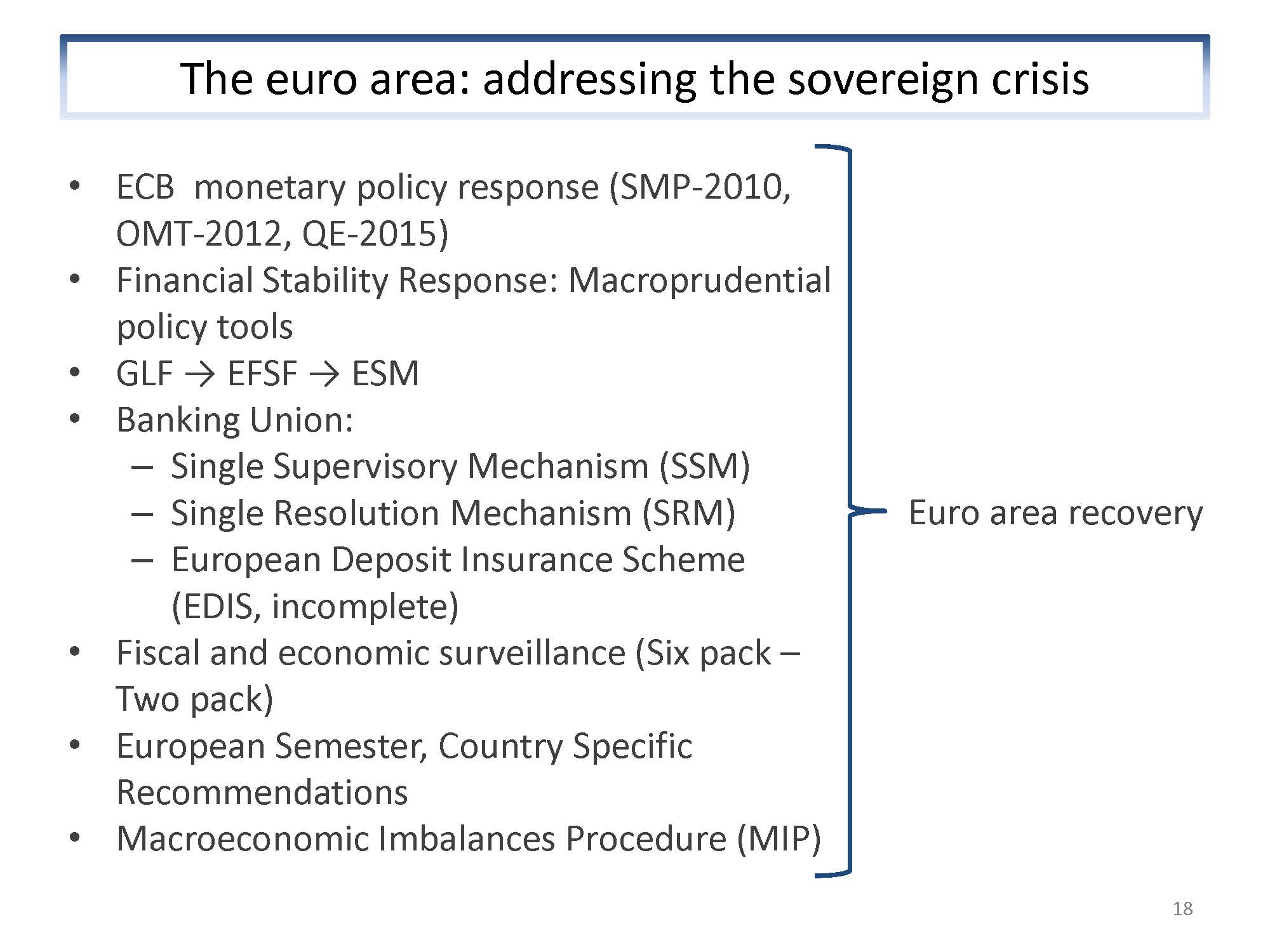

The ECB forcefully lessened country risks in 2012 with the announcement of unlimited Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) and the signal sent by ECB President Mario Draghi that the ECB would do “whatever it takes” to preserve the euro. More generally, the ECB has been addressing the severe and persistent disinflationary forces in the euro area with a broad set of standard and non-standard monetary policy measures. To a great extent, these measures have helped to improve financial conditions and boost the recovery in the euro area. Macroprudential policy tools are also now available to secure financial stability.

After the ad-hoc Greek Loan Facility that financed the first Greek bailout programme in 2010, the euro area set up the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) to provide financial assistance to distressed Member States. The EFSF was replaced by the more powerful European Stability Mechanism (ESM) in October 2012.

In response to the strong negative feedback loops between banks and sovereigns as well as contagion among national financial markets, European leaders, in 2012, initiated the Banking Union. Its three pillars are: the Single Supervisory Mechanism, the Single Resolution Mechanism and the still-to-be completed common Deposit Insurance Scheme.

Significant progress has also been made as regards fiscal and economic surveillance. The Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) was substantially strengthened by the adoption of the so-called “Six Pack”, and surveillance and coordination were enhanced through the so-called “Two Pack”. The European Semester, the Macroeconomic Imbalances Procedure and the Country Specific Recommendations are all contributing to stronger macroeconomic surveillance.

The way forward

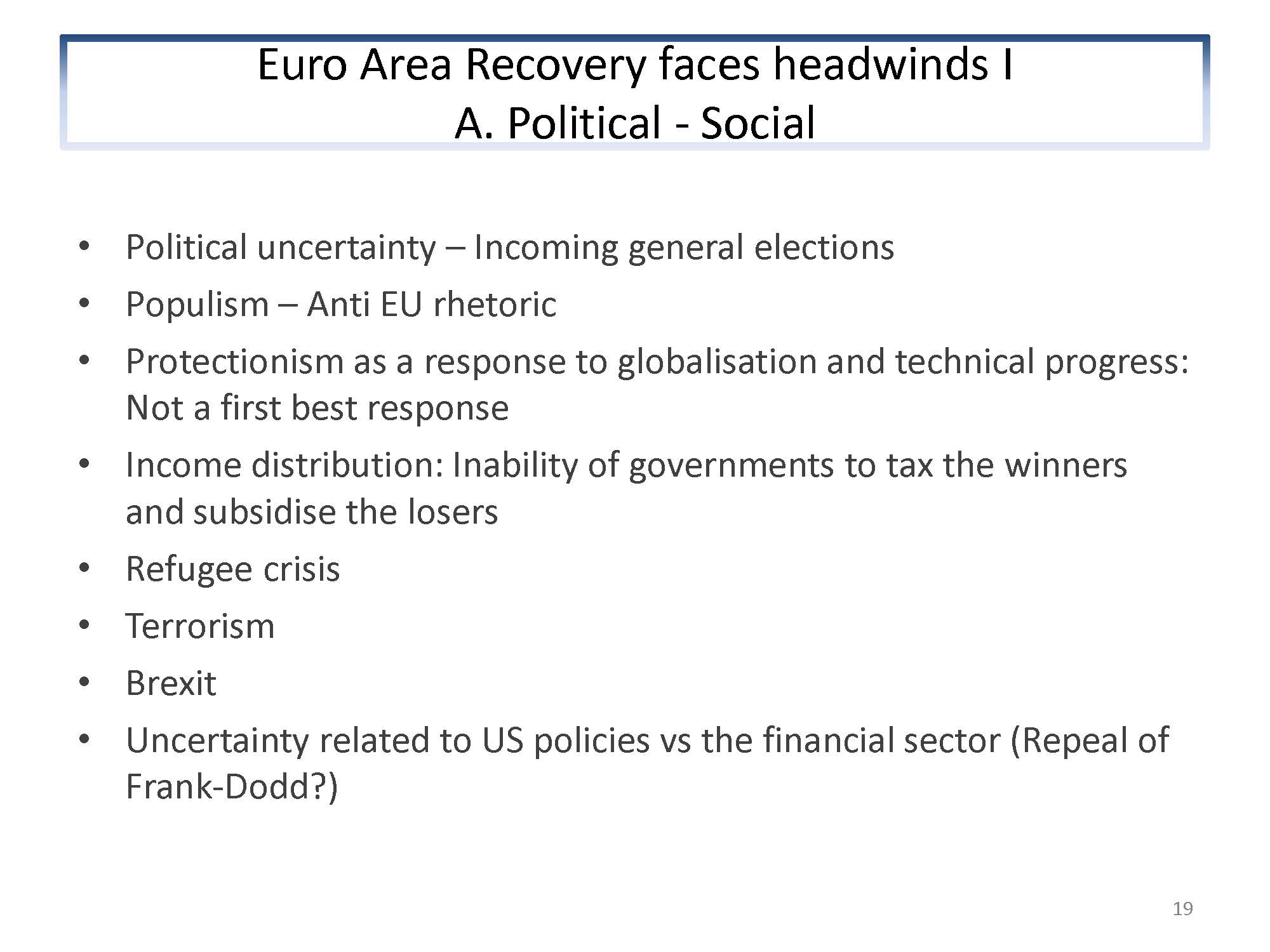

The euro area is now recovering. However, the recovery faces headwinds, relating both to political uncertainty linked to the rise of populism and anti-EU rhetoric and the surge of protectionist voices. The populist voices around the globe ‒ and particularly in developed economies ‒ can be traced to the undesirable consequences of globalization and technical progress. Yet protectionism is not a first best response. Specific concerns include the failure to tackle high and persistent unemployment, worsening income distribution, the fear that the influx of immigrants will affect societies’ identities and living standards, and tax evasion by multinational companies ‒ mostly related to uncontrolled off-shore activities. Additionally, the refugee crisis, fear of rising terrorism and Brexit generate more uncertainty. Finally, there are considerable worries related to US policy and especially its policies in the financial sector.

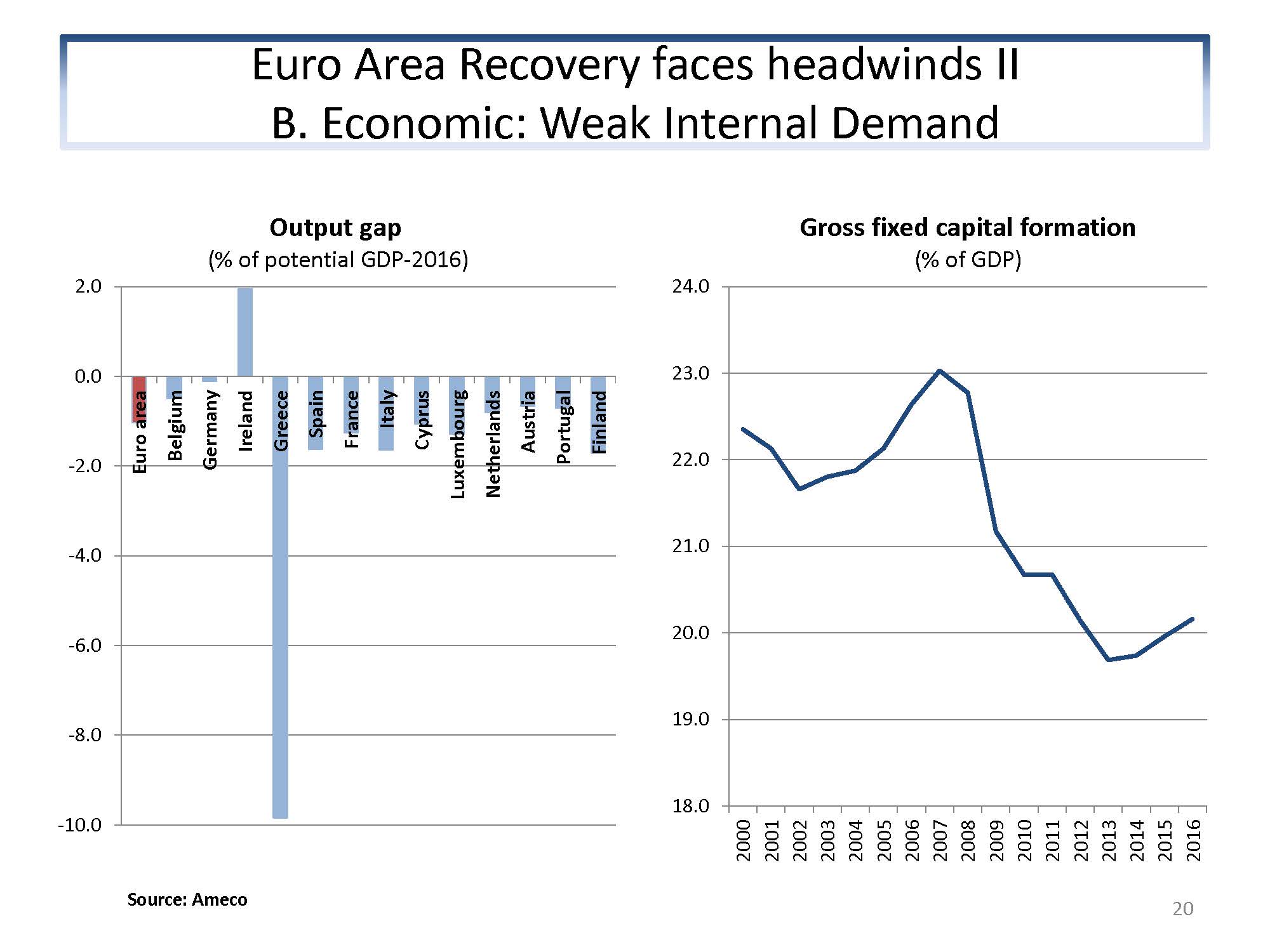

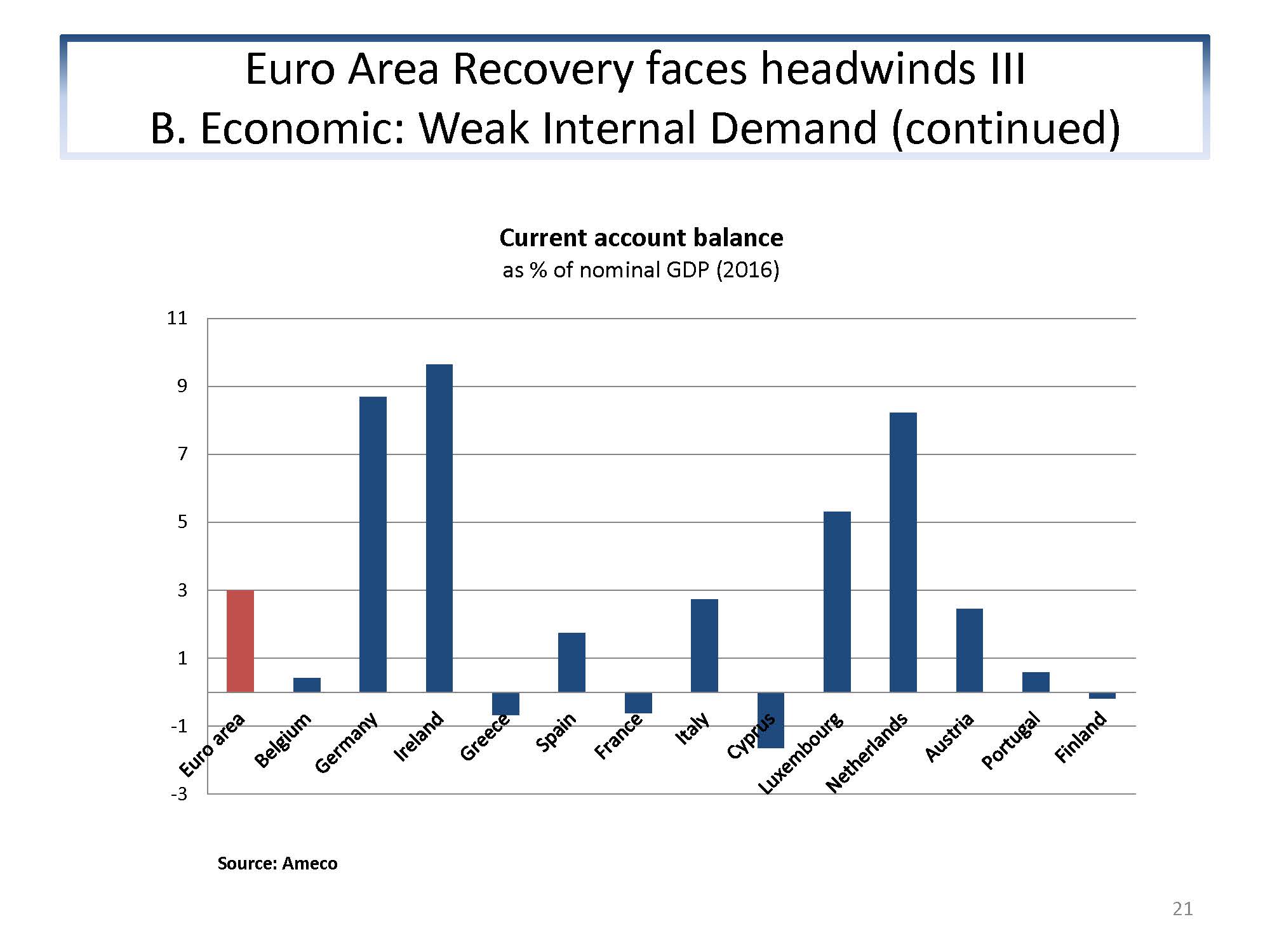

Moreover, the recovery in the euro area is slow compared to past recoveries, inflation remains persistently low, the output gap is still large in several Member States, investment as a share of GDP continues to be below its pre-crisis levels, and the rising current account surplus in the euro area as a whole reflects weak internal demand relative to production. Crisis legacies such as high and persistent unemployment, low total hours worked, high public and private debt are factors weighing negatively on recovery prospects.

In view of the aforementioned risks and challenges, and given the fact that the ECB cannot maintain loose monetary policy for ever, the way forward should involve structural reforms to improve potential growth, reduce structural unemployment and make the euro area more resilient to future shocks. Greater economic policy coordination, convergence and risk-sharing inside the euro area are also necessary.

Make the euro area more resilient to future shocks

Euro area economies should strengthen economic resilience by reducing their vulnerability and fostering smoother adjustment to future shocks. To achieve this, it is imperative to address crisis legacies and macroeconomic imbalances. In addition, member states should improve their capacity to absorb shocks internally. Building such a capacity implies removing rigidities in labour, product and services markets. This will support economic adjustment through price flexibility and facilitate a smooth and speedy reallocation of resources. Price flexibility allows for the recovery of any loss in competitiveness, and fosters a faster adjustment of relative prices, which, in the absence of exchange rate adjustment, is crucial for the rapid reallocation of production resources to the most dynamic sectors and firms.

According to a European Commission study, price flexibility and the rapid reallocation of resources require wage flexibility, ease of market entry of new firms, an effective and efficient insolvency framework including a second chance for entrepreneurs, a friendly environment for doing business, a well-functioning justice system, low levels of corruption, the availability of high quality public services and public infrastructure, and a regulatory framework conducive to competition.

Such reforms, besides increasing the capacity of euro area economies to absorb shocks internally, increase productivity and long-term growth. Furthermore, some structural reforms (for example, cutting red tape) raise expectations of future income, and thus boost confidence, investment and domestic demand in the short term, supporting the recovery. In addition, policies that raise labour force participation and reduce structural unemployment are essential to boost future growth and employment.

These reforms effectively make markets more flexible. But they can also make individuals’ lives more uncertain. To this end, it is important to improve social protection – a policy that has come to be known as flexicurity.

Reforms to the institutional setting of EMU to improve economic policy coordination, convergence and risk sharing

Euro area Member States should enhance real and cyclical convergence, which requires establishing closer economic policy coordination. Improved transparency and predictability in the interpretation and enforcement of fiscal rules (Stability and Growth Pact) and ownership and credible implementation of the country specific recommendations are prerequisites for successful policy coordination.

Furthermore, the adjustment mechanism within EMU should be facilitated by ensuring that it works in a symmetric way, i.e. both for countries with sustained external deficits and for those with sustained external surpluses. To this end, the Macroeconomic Imbalances Procedure should be strengthened and foster reforms in countries that have been accumulating large and sustained current account surpluses. Crisis stricken countries have improved their external positions on account of both higher exports driven by structural reforms and lower imports due to the economic recession. By contrast, countries that had high pre-crisis current account surpluses have not contributed to the much-needed rebalancing as domestic demand remains insufficient and potential growth low. This lack of progress in countries with sustained current account surpluses puts further strain on the adjustment efforts of deficit countries as it implies that more internal devaluation is required to achieve sustainable competitive gains. Moreover, this is even more difficult in the current low inflation environment.

Risk-sharing in EMU should be enhanced along the lines proposed in the Five Presidents’ Report in 2015 and other proposals, such as those released by the Jacques Delors Institute in the autumn of 2016. Private risk-sharing can be encouraged by actions that lead to a true financial union with fully integrated financial and capital markets. These actions involve completing the Banking Union, by creating a common Deposit Insurance Scheme and by setting up a credible common fiscal backstop to the Single Resolution Fund that underlies the Single Resolution Mechanism, perhaps by strengthening the financial resources of the ESM. There are various options for the formation of a common Deposit Insurance Scheme, some involve a re-insurance mechanism and lending arrangements between national insurance schemes, while others the formation of a single European Deposit Insurance Scheme. The ESM could be upgraded in order to become the fiscal backstop for the Single Resolution Fund and the common Deposit Insurance Scheme. Such steps are necessary to improve confidence in the banking system, break the feedback loops between banks and sovereigns and improve risk-sharing.

A genuine Capital Markets Union can be promoted through legislative changes that impose harmonization towards best practices on securitization, accounting, insolvency and company law, property rights etc. Such changes would allow for deeper integration of bond and equity markets and ensure that companies (and in particular SMEs) can gain access to capital markets on top of bank funding. The Capital Markets Union will enhance cross-border investment and consequently strengthen private sector risk-sharing across countries, as returns on assets and access to credit become less correlated with domestic economic conditions in individual Member States.

Besides enhancing the channels of private risk-sharing, a fiscal stabilization tool to cushion large macroeconomic shocks, that is, public risk-sharing, is warranted in the euro area. Such a tool, possibly administered by a euro area finance ministry with parliamentary legitimacy and responsibility, would provide essential insurance against asymmetric shocks that induce regional disparities, while, in case of symmetric shocks, it would complement the single monetary policy in its role as a cyclical stabilization tool, in particular when policy rates are at the zero lower bound.

Whilst there appears little appetite at present for fiscal union, there are alternative ways forward as proposed by both policy makers and academics alike. For example, building on the experience of the already-existing European Fund for Strategic Investments (the Juncker Plan), it would be politically feasible to strike a deal that promotes structural reforms in exchange for investment financed through a common pool of EU funds. These EU funds could come either from some intergovernmental investment fund or from the EU budget, while Eurobonds issued by the ESM could also be considered when conditions permit, using the appropriate conditionality. Such a “reform-for-investment policy” would provide the impetus for, on the one hand, more structural reforms that increase cyclical convergence and reduce macroeconomic imbalances and, on the other, more private and public investment that enhance productivity, spur convergence and foster social cohesion. Such a policy would thus strengthen both supply and demand. Public investment could be encouraged by including only amortization in the general government balance in exchange for reforms.

Alternative options involve a common unemployment insurance scheme, financed through social insurance contributions, or an all-purpose “rainy day” fund financed by annual contributions of Member States in good times. Such options could work to enhance the attractiveness of further integration in the euro area.

To avoid moral hazard, public risk sharing has to go hand-in-hand with greater coordination of economic policies and could be linked to the implementation of country specific recommendations and structural reforms, as well as sound and responsible fiscal policies in compliance with the existing EU rules. In the long run, a European Monetary Fund could be set up to replace the ESM. This Fund would act as a lender of last resort to member states. Governments in distress would be able to borrow from the Fund in exchange for ever tighter conditionality. The Head of the Fund would be the euro area finance minister and at the same time the EU Finance Commissioner. His/her remit would be to represent the interests of the euro area as a whole and he/she would be accountable to a Joint Committee of the European Parliament and the national parliaments.

Conclusions

Ladies and Gentlemen,

In conclusion, I want to emphasize that, despite the progress achieved in recent years, both Greece and the euro area face several challenges and risks ahead. There is no time for complacency because Europe is not adequately prepared for a new crisis and the ECB cannot maintain loose monetary policy for ever. Further action is imperative. The completion of the EMU along the lines proposed in the 2015 Five Presidents’ Report is a prerequisite for its long-term viability and the long-term prosperity of its Member States. That this will inevitably require changes to the Treaty is surely clear. But Treaties should not be written in stone. Periodic revisions are necessary to adapt to changing circumstances.

As regards Greece, the rapid completion of the second review and the consistent and determined implementation of the programme are prerequisites for ensuring a sustainable economic recovery. Moreover, following the recent approval of the short-term debt relief measures by the ESM and the EFSF, the completion of the second review would enable the adoption of decisions on medium- and long-term measures to ensure the sustainability of Greek public debt, and on the inclusion of Greek government bonds in the ECB’s quantitative easing programme.

The actions described above, if implemented, will set in motion a virtuous circle paving the way to the full return of the Greek government and Greek businesses to international financial markets and the gradual relaxation and ultimately the lifting of capital controls. Such developments will signal the definite exit from the sovereign debt crisis, the return to financial normality and to sustainable medium-term growth.

Related link: Presentation