Good afternoon, everyone.

It is an honor and a privilege to be at the Bank of Greece and I would like to start by thanking Governor Yannis Stournaras for the invitation.

For decades, the global economy enjoyed the tailwinds provided by institutions and ideas that shaped the post-World War II order. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences captured this spirit in 2024, awarding the Nobel Prize to Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson for their work on how institutions drive prosperity. Their message is clear: Societies thrive when institutions foster inclusion, innovation, and stability—not extraction or stagnation.

This institutional foundation—education, welfare, labor protection, antitrust, and democracy—underpinned the golden era of globalization. The Bretton Woods system, central bank independence, and the spread of trade and capital mobility created a world where more countries, people, and firms shared in growth.

Labor mobility, once secondary to capital, became central as skills and integration deepened. Vertical supply chains and interdependencies fueled innovation and prosperity.

Societies invested in education and skills which generated positive general equilibrium spillovers, since the opportunity cost of holding human capital idle or misallocated became increasingly unbearable.

These changes through the labor market created the conditions for a smoother and more efficient adjustment, buffering the transmission channel of monetary policy — the channels through which interest rates curb demand and inflation. The sacrifice ratio, defined as the increase in unemployment for each 1% drop in inflation, once macroeconomists beacon of success, was made irrelevant due to more efficient private sharing mechanisms originated in the labor market.

An efficient transmission of monetary policy requires markets to work efficiently. Recent developments in the European economy highlight challenges to the transmission channels. I will take some of them today.

Institutions took us through periods of rapid growth and crisis, not to create a society that is pristine, but one that seeks constant improvement. The global economy as we knew it before the pandemics had its own drawbacks, but was the result of endless efforts, for centuries, to connect people and cultures.

Today, the old rules are unraveling. Deglobalization, friend-shoring, and protectionism are not just reactions to fragility—they are active choices, reshaping trade, fiscal policy, and financial stability. For monetary policy, this matters profoundly.

Surely, headwinds make most of the news, but there is also potential good news in the pipeline, and I will talk briefly about one: the generalized usage of Artificial Intelligence. I will take the stance that it is both a promise and a peril.

I will suggest that you think about the labor market in the following way: a massive private sharing mechanism, that generates more than two thirds of households’ disposable income, and that is operated by firms and employees, always under the incentives provided by institutions.

Can monetary policy navigate this turbulence? Can we rebuild momentum when trade is fragmenting, deficits are rising, and bubbles are inflating? Or are we entering an era where the tools of stability—fiscal discipline, open markets, and adaptive labor policies—are no longer within reach?

Let me explore these challenges—and the labor market’s unexpected role as both a stabilizer and a beacon of hope.

- Trade Fragmentation: Disruption and Inflationary Pressures

Trade fragmentation is reshaping globalization. As Richard Baldwin notes, “The era of hyper-globalization is giving way to a more fragmented, regionalized trade system.” For monetary policy, Blanchard points out that this shift disrupts global markets, creating persistent inflationary pressures that complicate central banks’ ability to meet their targets.

The current outlook is marked by uncertainty, driven by frequent trade policy changes and the challenges of reoptimizing production and distribution. Fragmentation undermines firms’ ability to achieve returns that reflect marginal costs, leading to persistently lower investment and further price pressures. This is a sort of holdup problem, and a good definition of a headwind. Structural shocks like tariffs require time and innovation to restore profitability and pre-tariff price levels.

Tariffs act as a damaging tax, affecting the entire production and consumption cycle. Their impact on prices depends on market power and elasticity: if demand is elastic and supply inelastic, exporters may absorb the cost; if not, tariffs pass through to consumers, fueling inflation. Either way, the economy shrinks until technological progress offsets the damage.

Market Adaptation in an Era of Trade Fragmentation

The market’s response to the fragmentation of trade has spanned the full spectrum of strategic adjustments. Elasticities command the shift, and new markets have emerged. History shows that no single player—no matter how dominant—can indefinitely hold markets captive. Industrial organization theory confirms this (I will make a parallel with the theory of quasi-monopoly): The "residual market" (the market excluding the quasi-monopolist) becomes more competitive and integrated over time, eroding that player’s market power. The prescription being (as for competition authorities) for us to concentrate in developments in this residual market.

Bilateral agreements are proliferating—not just as stopgaps, but as durable frameworks. Unlike multilateral arrangements, these agreements are harder to dismantle and reduce the contagion risks associated with the breakdown of global trade systems. In this fragmented landscape, regional blocs are not just adapting; they are rewriting the rules of engagement.

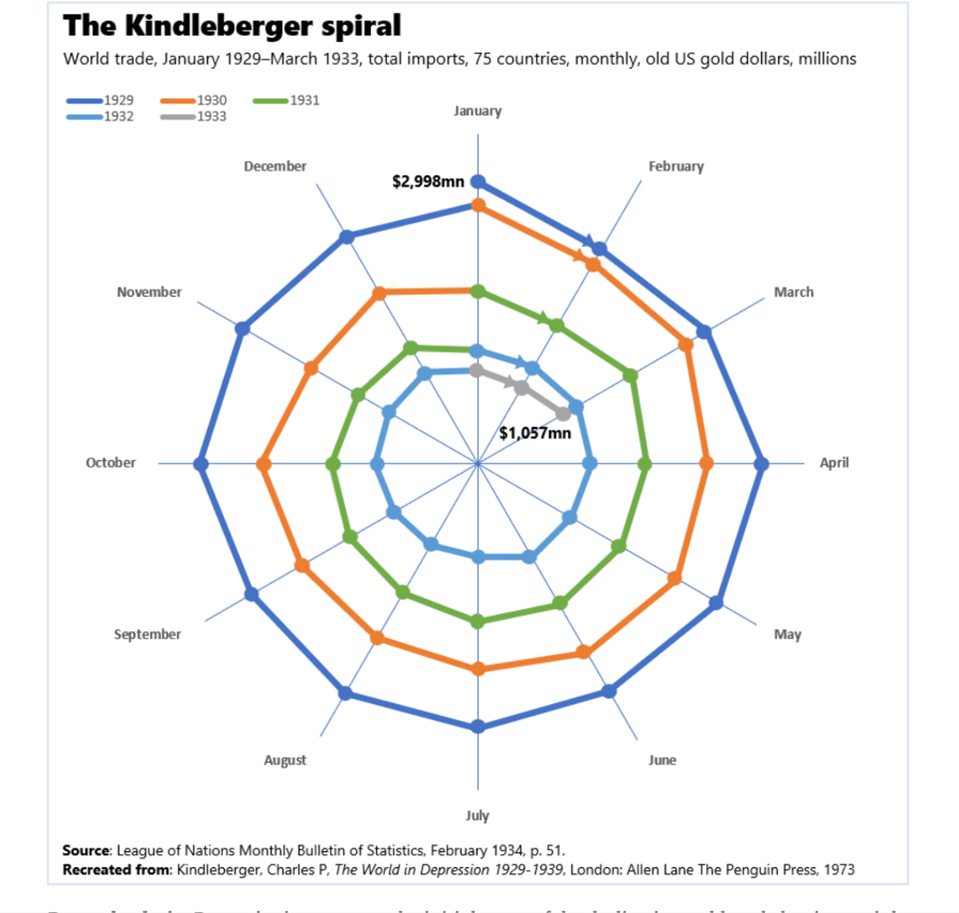

Trade fragmentation following a tariffs war, with generalized retaliation can be destructive to international trade. The Kindleberger Spiral, named after the economic historian Charles Kindleberger, represents the catastrophic decline in global trade between 1929 and 1933. Its spiral shape illustrates the month-by-month contraction in trade, showing how retaliatory tariffs, such as the U.S. Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, contributed to the economic downturn of the Great Depression.

Trade has been a cornerstone of economic growth in the last eight decades, replacing it requires an adjustment process that no economy is in conditions to undertake.

Key takeaway: Trade fragmentation disrupts markets, undermines monetary policy transmission, and lowers natural interest rates, creating a challenging environment for central banks.

- High Fiscal Deficits and Fiscal Dominance

The Challenge of Procyclical Fiscal Policy

Fiscal policy should act as a countercyclical stabilizer. When expansionary fiscal policies persist during positive output gap periods, they force central banks to tighten monetary policy, creating inefficiencies and heightening uncertainty.

For those new to the field of defining economic policies I can reveal one basic principle: the harsh truth is that economic policies are meant to be boring, to provide stability across the business cycle, to smooth out every bit of excitement that the business cycle may bring about.

However, the current policy stance emphasizes the conflict between fiscal and monetary objectives, which undermines policy credibility and economic stability.

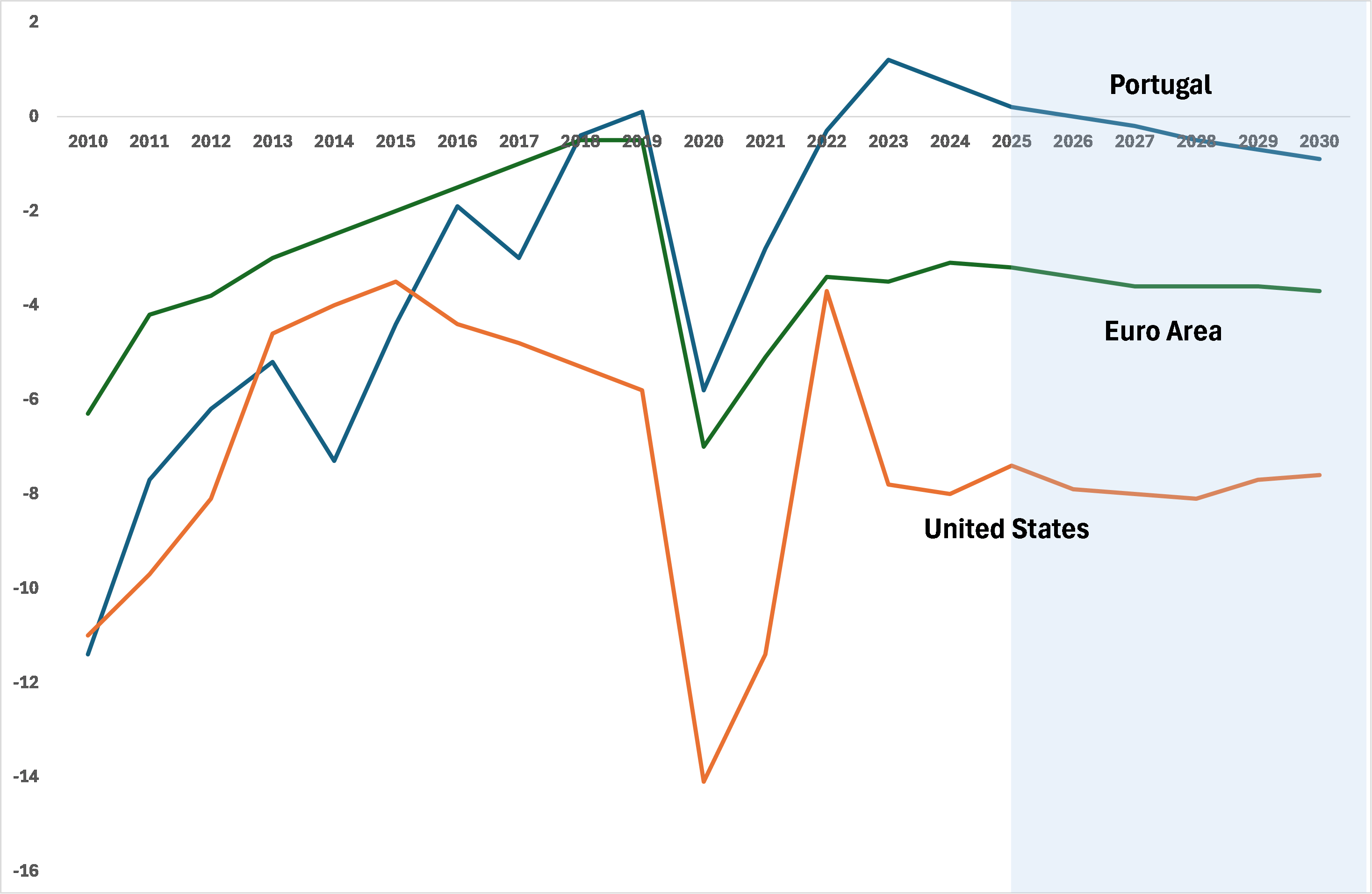

Fiscal policy in the United States and the Euro area operate under different institutions. The prevailing differences explain why, over the past 15 years, the euro area has focused on reducing sovereign risk, while the U.S. has largely sidelined concerns about the sustainability of its public debt.

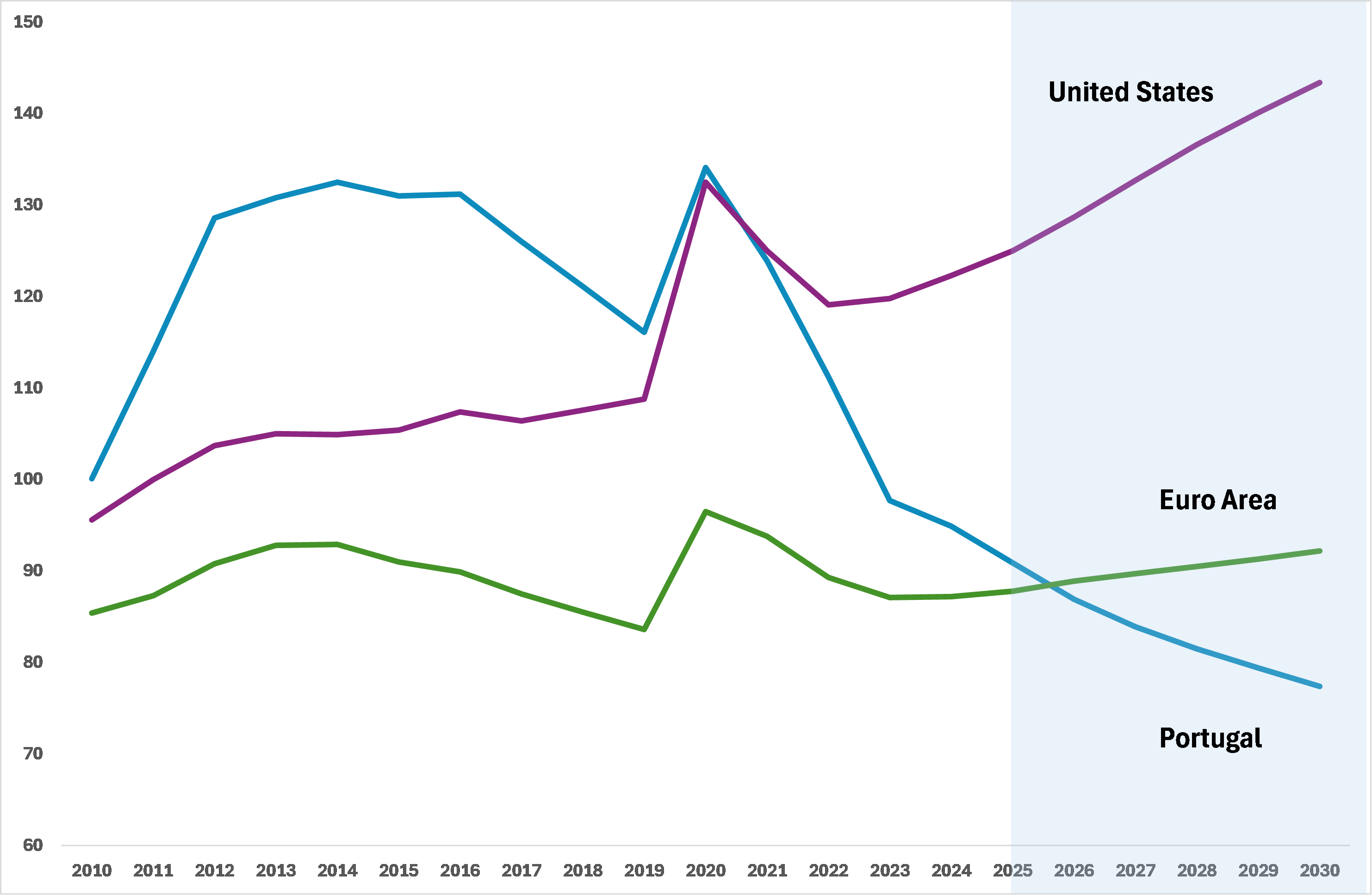

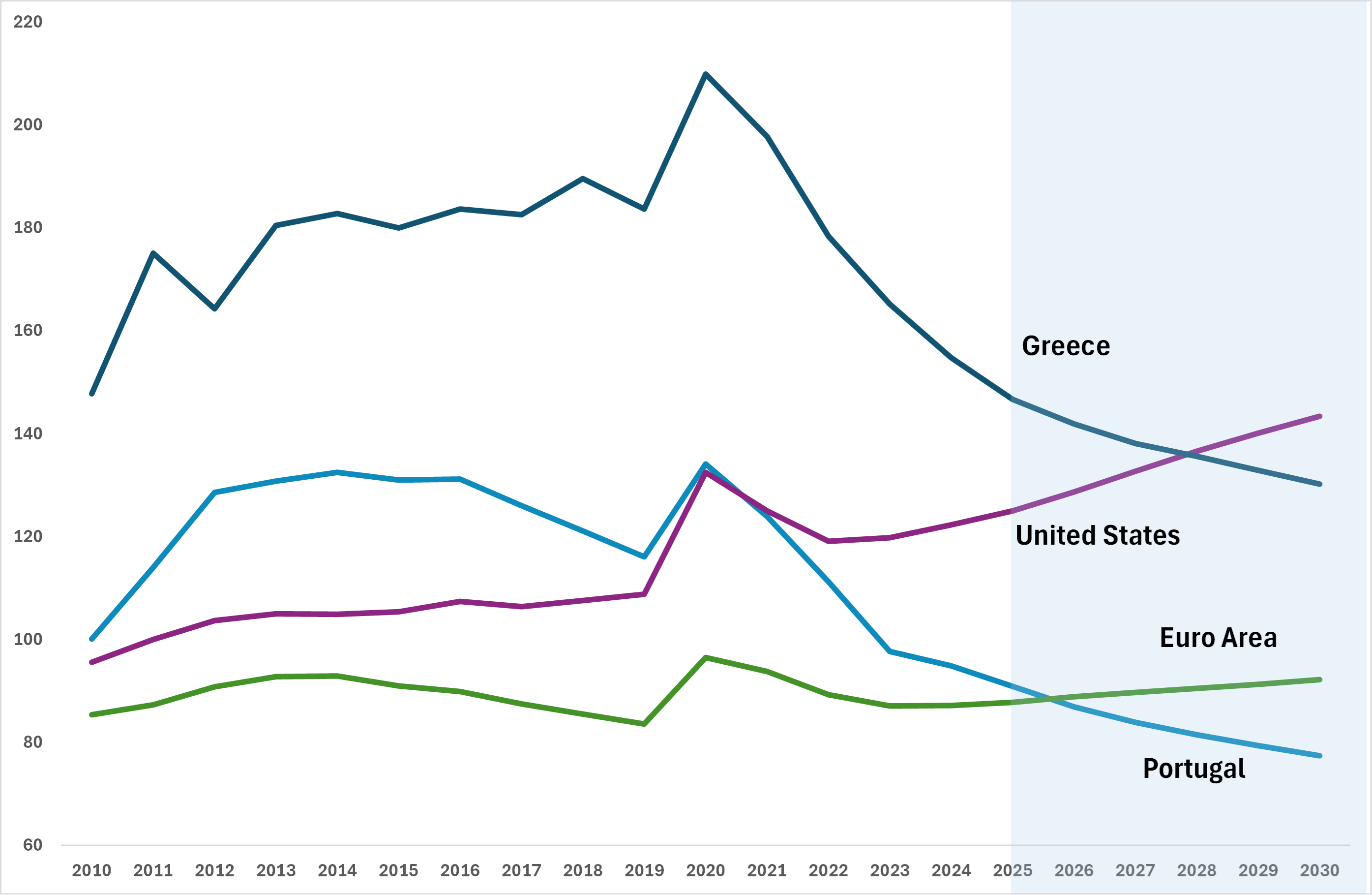

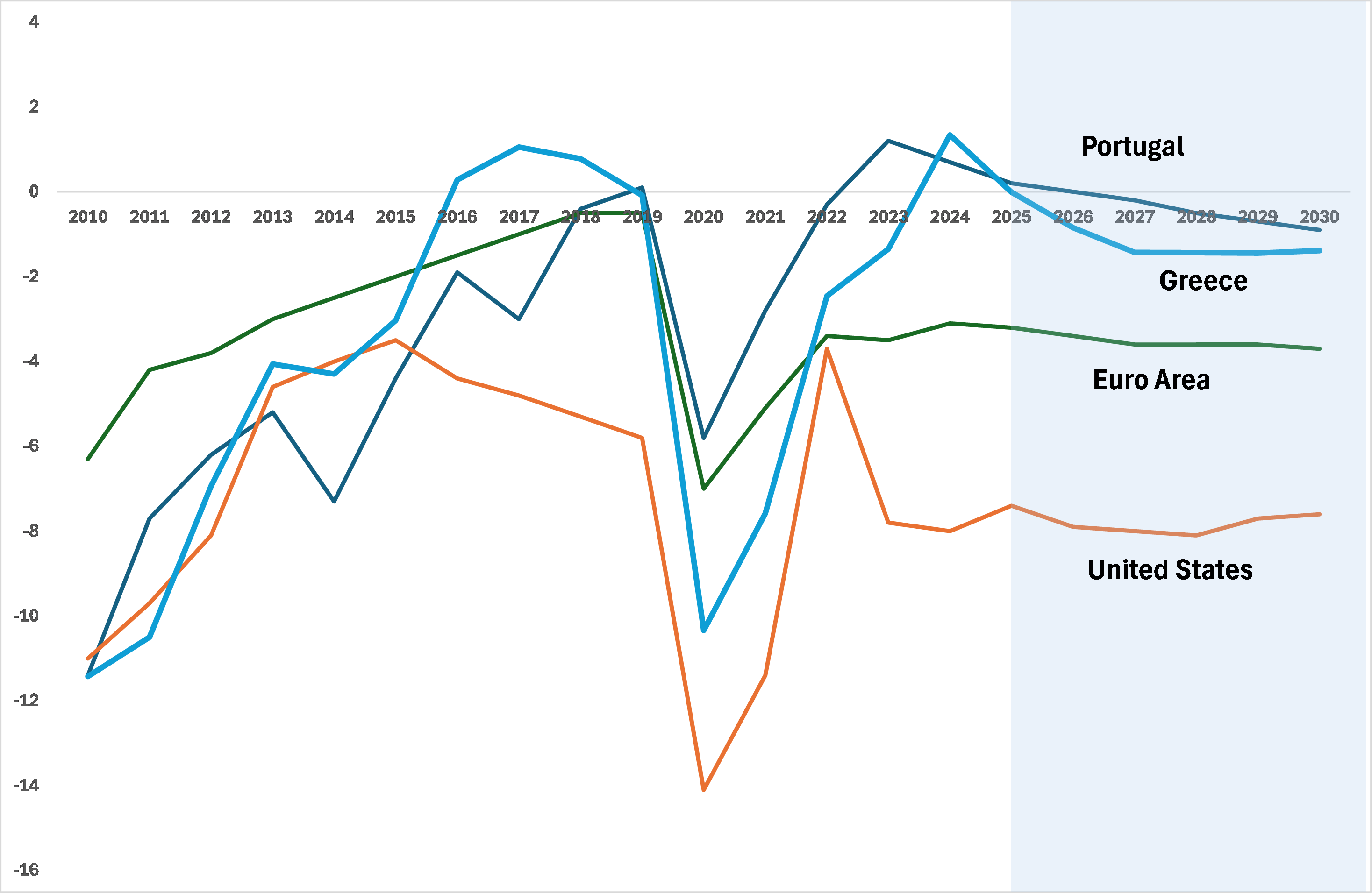

Figures 1 and 2 highlight the stark divergence in public finances between the United States and the Euro Area over the past 15 years.

In the Euro Area, the figures are modest: 85.4% in 2010, 87.8% in 2025, and a projected 92.2% by 2030. On the contrary, the United States debt stood at 95.6% of GDP in 2010, surged to 125% in 2025, and is projected to reach 143% by 2030.

The contrast is even sharper when examining fiscal deficits. Since 2015, United States net borrowing has consistently outpaced that of the Euro Area.

When considering "accumulated deficits" between 2010 and 2030 (with caution, given the limitations of summing annual figures as a share of GDP), Euro Area’s total is 69%, and United States are projected to cumulate to 153% of annual GDP, more than double.

The European Lesson: Coordination of Monetary and Fiscal Policies

Europe’s economic policy framework has evolved significantly since the creation of the euro, one of the world’s youngest currencies. Its institutions continue to adapt, reinforcing the euro’s role both domestically and internationally.

Equipped with better instruments, the coordination (or cooperation, as some prefer) of fiscal and monetary policies has been a cornerstone of Europe’s credibility. This synergy helps explain the region’s recent success in navigating both the economic crisis and the inflationary pressures that followed. By aligning fiscal discipline with monetary independence, Europe has demonstrated how integrated policy frameworks can foster stability and resilience in an uncertain global economy.

Figure 1: General Government Gross Debt as a Share of GDP (Source: IMF)

Figure 2: General Government Net Lending/Borrowing as a Share of GDP (Source: IMF)

Before moving away from Fiscal territory, let me publicize a Case Study: Portugal’s Fiscal Adjustment

Portugal’s post-2012 fiscal reforms stand as a benchmark for successful adjustment.

Confronted with debt soaring to 129% of GDP and deficits nearing 6.4%, Portugal implemented structural changes—including conservative pension indexation and linking the retirement age to life expectancy—while reducing public spending from 50.6% to 43.8% of GDP. The results were striking, by 2023, debt had fallen to 98.7% of GDP, and the country returned to budget surpluses (the first surplus in the democratic period occurred in 2019).

Figures 1 and 2 trace Portugal’s public finance trajectory since the Great Financial Crisis, revealing a story of divergence turned into success—a testament to the resilience of reforms that endured political and economic cycles.

- Asset Bubbles: The Third Dimension of Monetary Policy Challenges

Trade fragmentation and high fiscal deficits are not the only headwinds facing monetary policy. Periodic asset bubbles further complicate the picture, as central banks grapple with the risk of financial instability.

In 2025, both the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank have flagged “elevated asset prices.” The S&P 500’s Shiller CAPE ratio stands at 41 — 3,2 standard deviations above its historical mean of 17 — while housing markets show signs of strain. In Miami, for example, the price-to-income ratio has reached 8.5, compared to a historical norm of 3.

Yet, traditional policy frameworks like the Taylor rule, which focus narrowly on inflation and employment, ignore these signals. As Armen Alchian and Benjamin Klein argued in their 1973 paper, “On a Correct Measure of Inflation,” asset prices often reflect underlying inflationary pressures. Neglecting them, risks repeating the instability seen in 2008.

Key takeaway: Asset bubbles, driven by loose monetary conditions and uneven market dynamics, add another layer of complexity for central banks. Ignoring these risks—whether in equities or housing—could undermine financial stability, just as trade fragmentation and fiscal dominance limit the tools available to central banks, asset bubbles force them to choose between financial stability and economic growth. In this context, macroprudential regulation (e.g., stress tests, capital buffers, borrower-based measures) is becoming the first line of defense of financial stability and as important as traditional monetary tools.

- The AI Tailwind: Promise and Peril

Some herald AI as a transformative tailwind for total factor productivity (TFP). While I share this optimism, I urge caution. AI is a general-purpose technology, its spread accelerated by the exponential improvements in hardware—now accessible even through smartphones. Yet, as history shows, the adoption of revolutionary technologies is rarely linear.

AI’s roots trace back over a century—from IBM’s founding in 1911 to the rise of digital computing and the internet—yet TFP growth in the U.S. averaged just 1.1% annually from 2000 to 2020, according to the BLS. Even the dot-com boom of the 1990s, which promised a productivity revolution, saw TFP peak at only 2.5%. AI’s economic impact, therefore, is likely to be gradual, not an overnight panacea.

Caution is warranted. Every technological leap reshuffles power among sectors, people, and nations. The opaque nature of AI algorithms and datasets demands robust surveillance and traceability mechanisms, which remain largely absent. As Alain Supiot has argued, information is power—and the scale of data mining today is unprecedented. Martin Gurri, in The Revolt of the Public, highlights the profound information overload facing society: more data was generated in 2001 than in all human history prior. And in 2002, information double. And that was more than 20 years ago! The implications for sovereignty, privacy, and social cohesion are profound.

Yet, if we navigate these risks wisely, AI’s potential to generate wealth could be redistributed to benefit the global economy. The challenge shifts from mitigating disruption—mass unemployment and displacement—to actively shaping policies that harness AI’s benefits. We cannot run into the mistakes made with globalization. We must use the returns from AI to help with the transition for those eventually displaced from the labor market in a structurally way. This is not an insurmountable obstacle, but a task we can identify, understand, and address. Just as trade fragmentation and fiscal deficits require patient, adaptive policy responses, so too does the integration of AI into the global economy.

- The Labor Market: A Cornerstone of Monetary Policy

The labor market has long been the overlooked element in both empirical and theoretical analyses of monetary policy. During the inflation surge of 2021–2022, most discussions about the labor market focused narrowly on wages—particularly the risk of "second-round effects" through the feedback loop between prices and wage costs. While these effects are straightforward to describe, they are notoriously difficult to identify empirically. The challenge lies not in their existence, but in the fact that the transmission channel is not wages per se, but broader labor costs and adjustments. More critically, the labor market’s structural response to inflation and economic growth often has a more profound impact on price stability than wage-setting alone.

Structural Rigidities vs. Flexibility A sclerotic labor market—characterized by sluggish employment adjustment, skill erosion from long-term unemployment, and segmented labor pools—can exacerbate inflationary pressures more than wage dynamics alone. Conversely, a flexible and mobile labor force can absorb wage increases without triggering cost-push inflation, as firms adjust pricing decisions more smoothly.

The Euro Area: A Test Case for Optimal Currency Areas The euro area adds a unique layer to this debate: Is it an optimal currency area (OCA)? The OCA theory argues that a single currency works best when the benefits (e.g., lower transaction costs, deeper trade integration) outweigh the costs of relinquishing independent monetary policy and exchange rate flexibility. Key OCA criteria include high labor mobility, wage flexibility, integrated capital markets, and synchronized business cycles—all of which enable regions to adjust to shocks without exchange rate tools.

Focusing on the labor market dimensions:

- Labor Mobility: Workers must be able to relocate easily to regions with labor demand, balancing unemployment in one area with shortages in another.

- Wage and Price Flexibility: Adjustments in wages and prices act as a critical shock absorber when exchange rates are fixed.

Europe’s Labor Market: From Laggard to Leader Historically, the euro area’s labor market was criticized for its rigidity: persistent long-term unemployment, slow employment recovery, low job creation, sticky wages, and institutional barriers like employment protection and union influence. However, recent years tell a different story—one that warrants recognition.

During the inflationary episode and post-pandemic recovery, nominal and real wages in the euro area adjusted in ways that mitigated cost pressures, contrasting with the U.S., where real wage gains emerged earlier in the inflation cycle.

Figure 3: Real hourly compensation – Euro Area, y-o-y (%). Source: Eurostat.

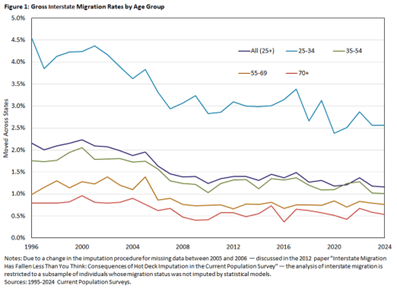

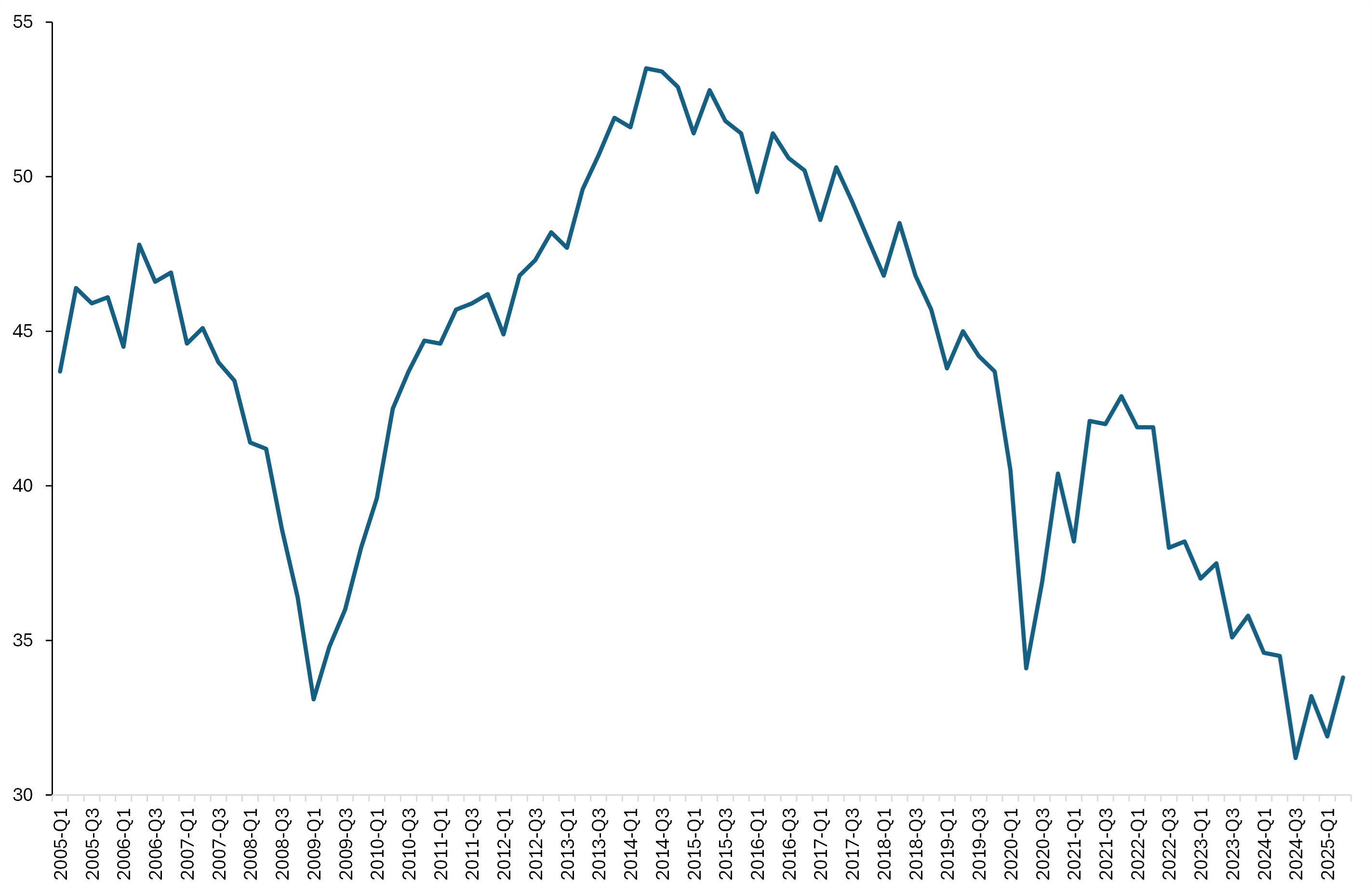

One of the main novelties in Europe is labor mobility. Europe added more than 12 million jobs in the last 5 years. A dynamism never seen in the last 5 decades. During the same period foreign-born workers increased by 7,3 million. 60% of the net employment gain were driven by intra-EU migration and inflows from outside the bloc (Figure 4). In the euro area, the percentage of workers that are foreign-born increased in a sustained way at least since 2005, but particularly after the pandemics, from 13% to 18%.

This contrasts with the declining labor mobility in the United States over the past two decades (Figure 5). Interstate gross migration declined for all age groups, but specially for young workers.

Figure 4: Percentage of employees born outside the country in which they are employed, Euro Area. Source: Eurostat.

Figure 5: Gross interstate migration rates, from Jones at al, Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

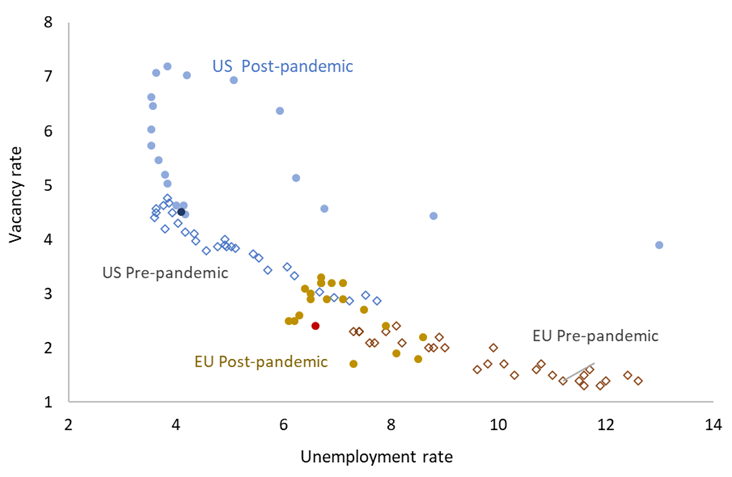

Labor economists measure labor market efficiency using the relationship between unemployment and vacancies, the so-called Beveridge Curve. The closer to the axis the curve is, the more efficient will matching be in the economy; we will need fewer unemployed to fill a given number of vacancies; or, we need a smaller number of vacancies to match with a given number of unemployed.

Crucially, the euro area’s Beveridge curve did not shift outward, unlike in the U.S., signaling a more efficient matching of labor supply and demand (Figure 6). This flexibility helped the euro area navigate both the pandemic and inflationary shocks, extending the pre-COVID employment and wage momentum into the post-COVID era — even as monetary policy tightened by 450 basis points, the sharpest increase in modern history.

Figure 6: Beveridge curve – United States and Euro Area (in percentage). Sources: BLS and EUROSTAT.

Thanks to robust furlough schemes implemented across the continent, Europe managed to avoid the severe job losses seen in the United States. In the first two quarters of the pandemic, the U.S. lost a staggering 23 million net jobs, while the euro area’s employment reduction was limited to just 5 million.

A sharp reduction in employment in just two quarters poses a real administrative challenge to any unemployment benefit system, and rehiring this many workers by firms was a dire task and a true stress test to any matching function, as efficient as it could be. Massively hiring workers also entails a pressure on renegotiated wages, under substantially different conditions.

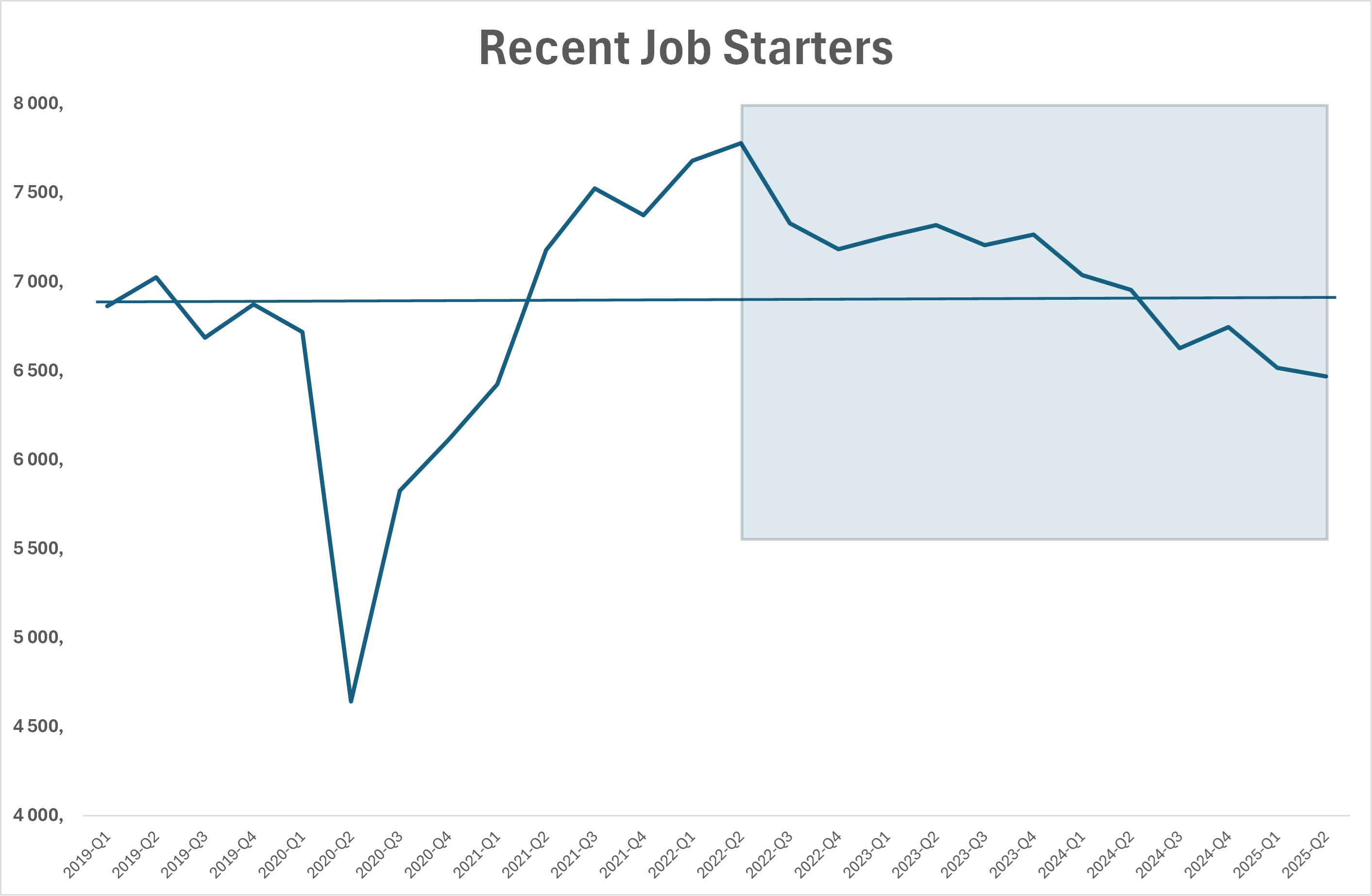

The bust and boom of new jobs

The recovery from the pandemics was faster than expected. This rendered credit to the policies implemented in Europe. However, as expected, during the early quarters of the crisis, new jobs (those with less than three months of tenure) plummeted from around 7 million to slightly above 4.5 million. Remarkably, after the second quarter of 2021, new matches jumped to figures above pre-pandemic and they remain high as long as the loss in new jobs has been recovered (Figure 7).

The number of new matches is now 6% below pre-pandemics level.

Figure 7: Recent Job Starters (Matches Formed in the Last Three Months) (Source: Eurostat)

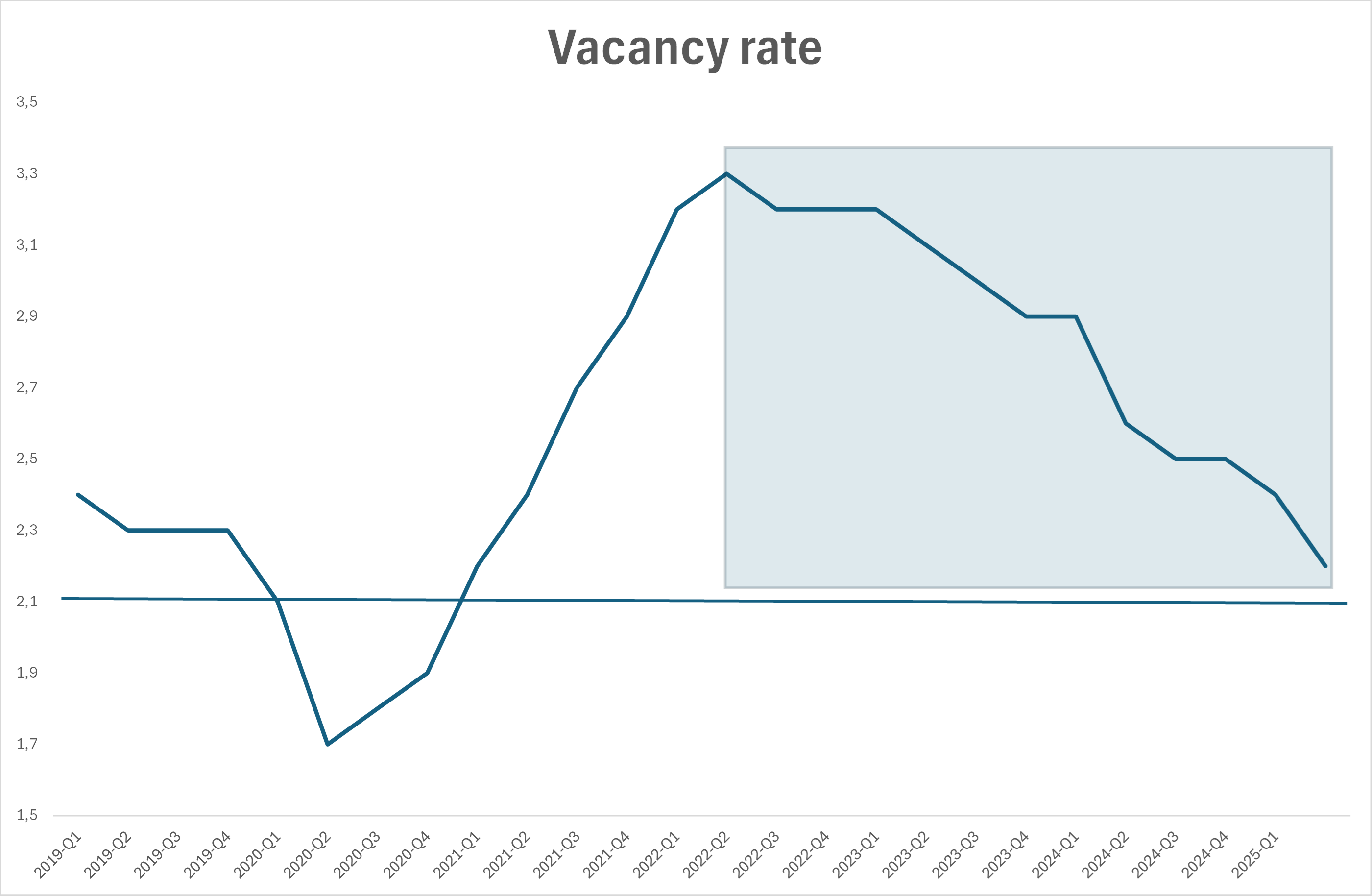

The same evidence can be obtained from the vacancy rate data. Vacancies available fell initially with COVID, but they recovered quickly staying above pre-pandemics since then (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Vacancy rate. Source – EUROSTAT.

Note that monetary policy is inflicting costs in the labor market. Both new jobs and vacancies show a slowdown as the monetary policy hiking process took stage. The vacancy rate fell from 3,3% in the second quarter of 2022 to 2,2% in the second quarter this year – a reduction of one third. The number of recently formed matches is 17% below the figure for the second quarter of 2022.

This was expected not only because of the completion of the recovery from the pandemics, but also because of a tighter monetary policy in markets through reduced credit and global demand. We can say that the transmission channels of monetary policy into the labor market were fully in place.

Are we requesting too much from the labor market adjustment?

A counterfactual analysis of the adjustment of the economy to the pandemic and inflation episodes using the labor market characteristics of the 80s and 90s would deliver a different image of Europe. The labor market is not the sole responsible, the euro itself, and the conditions for financial stability achieved through reform and risk reduction must also be considered. But there is no doubt that higher and long-term unemployment, sluggish wage and employment adjustment, would have delivered lower growth and a more painful recovery from the pandemics and disinflationary period.

Despite this positive appraisal, we cannot disregard the fact that Euro area growth remained contained. Here, also, a proper evaluation is yet to be obtained. Sustained by a massive fiscal impulse and a slower disinflation process, the United States has been growing faster than the Euro Area.

If employment is a derived demand, low growth will not sustain high employment for a long period of time. No one knows when and if the labor market will yield, but a healthy real wage recover will only be possible with a pickup in growth.

While, labor supply mobility and increased skills facilitated price and wage adjustments, if investment and growth do not feed into this process, promoting an increase in productivity, the sustainability of the overall process can be rightly questioned. The remedies are well-known: structural reforms that promote growth; more European integration and full-usage of the internal market; coordination of monetary and fiscal policies; and completion of the institutions in the financial and banking sectors.

A word on unemployment to underline the improved quality of Europe’s adjustment, namely the composition of its pool. The share of long-term unemployed has fallen to its lowest level in two decades, from the peak of over 50% during the sovereign debt crisis to close to 30% today. This shift reflects not only a full-employment economy, but also a more dynamic and efficient labor market, which lead to an inclusive recovery, where workers are re-entering employment faster and more efficiently (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Long-term unemployment – Euro Area (share 12 of more months unemployed). Source: EUROSTAT.

Education: The Engine of Labor Market Efficiency

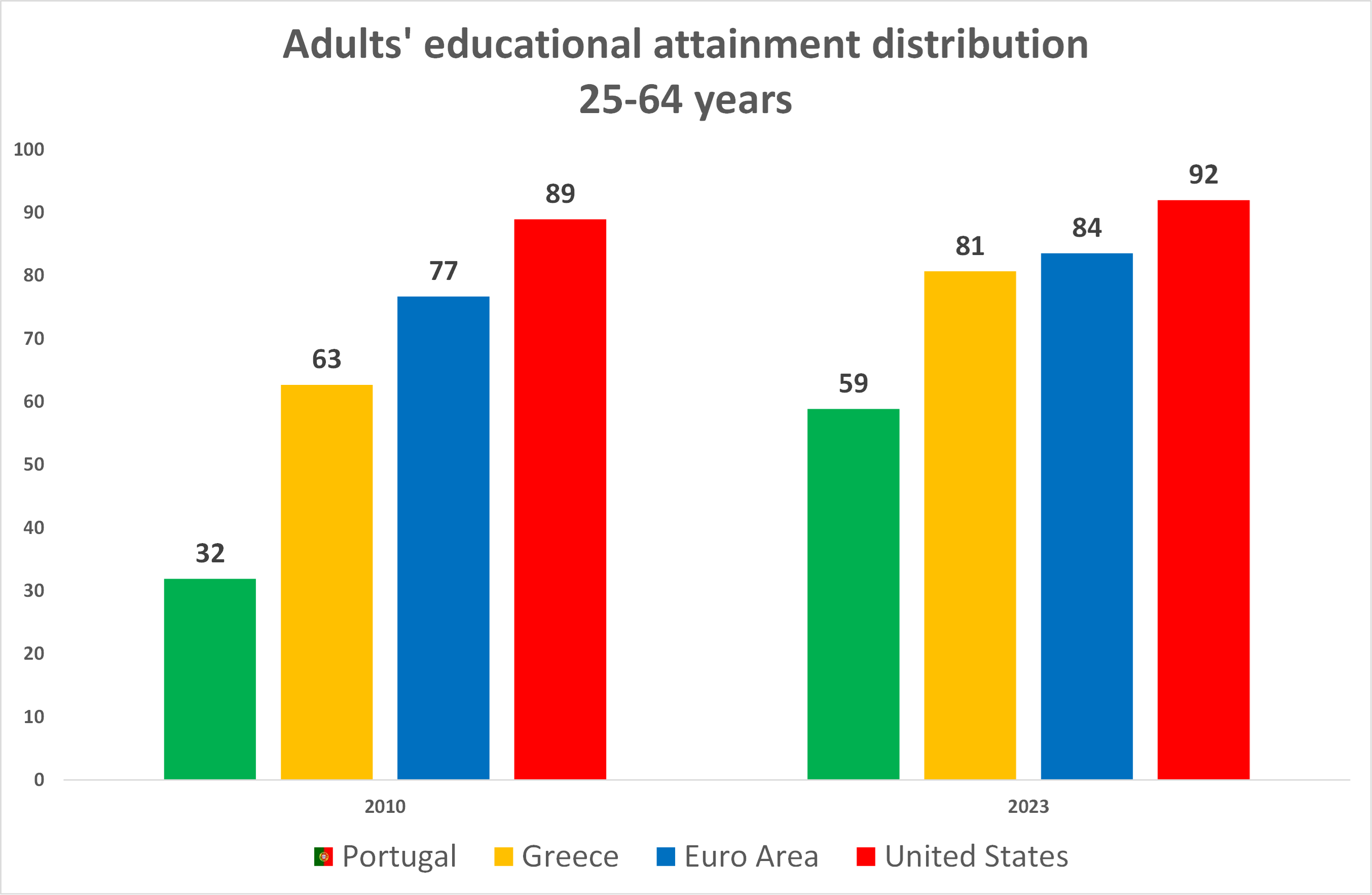

Education is the grease that keeps the labor market running smoothly and enhances the quality of its adjustments. Education changes labor market dynamics. It empowers workers and firms to demand—and achieve—better matches, much like other institutions such as minimum wage laws, unemployment insurance, or unions. Education doesn’t just influence individual outcomes; it reshapes the entire labor market equilibrium.

There is reason for optimism here. Today’s labor market benefits from a far more educated workforce than just 15 years ago. In the United States, for example, 92% of the working-age population now holds at least an upper secondary education, with 51% possessing a college degree—up from 42% in 2011. The Euro Area, while still catching up, has also made progress: 89% of its working-age population has completed upper secondary education, and 37% hold a college degree, compared to just 29% in 2011.

Figure 10: Adult’s educational attainment, 25-64 years. Source: OECD

Figure 11: Adult’s educational attainment, 25-34 years. Source: OECD

This progress aligns with the insights of Nobel Laureate Philippe Aghion, who has long argued that innovation thrives at the frontier of knowledge—and that frontier is populated by the most educated societies. In a 2010 keynote at the Banco de Portugal, Aghion reviewed Portugal’s educational statistics—where only 30% of the population held at least an upper secondary degree—and concluded that the best path forward was imitation. This lag was partly a legacy of underinvestment during the dictatorship era, but even among younger generations, Portugal still trailed all developed economies. Today, Portuguese youths enter the labor market with schooling close to that of more developed economies: 45% are college graduates.

A Labor Market Transformed

My aim here has been to challenge the conventional narrative about Europe’s labor market. For years, research and discourse have framed it as a source of concern—rigid, sclerotic, and resistant to change. Yet today, the story is different. The data paints a picture of resilience, adaptability, and progress. While challenges remain, the labor market’s evolution—driven by education, flexibility, and policy innovation—offers a rare and compelling reason for optimism.

Conclusion: Labor Markets as a Source of Stability The euro area’s labor market has evolved from a liability to a pillar of stability. Its increased flexibility has not only cushioned the impact of recent crises but also allowed employment to reach historic highs. This resilience underscores a critical lesson: A well-functioning labor market is not just a byproduct of monetary policy—it is a prerequisite for its success.

- Conclusion: Forging a New Consensus

The headwinds we face—trade fragmentation, fiscal dominance, and asset bubbles—demand fixes. We need a Bretton Woods 2.0: a framework fit for a multipolar world, where competition is channeled into shared prosperity, not zero-sum conflict. History shows that rules matter. Well-designed incentives can reduce poverty, curb wealth concentration, and align economic decisions with public good. Cooperative trade policies can stabilize prices and restore predictability. Fiscal reforms, as Portugal demonstrated, can break the cycle of debt and austerity. And macroprudential tools can tame asset cycles before they spiral into crises.

Reason has carried us through crises before. Let it prevail again.