Speech by Bank of Greece Deputy Governor John (Iannis) Mourmouras at the Amundi Asset Management’s Asset and Risk Management Seminar in London: “Τhe risks and prospects for the global economy and capital markets in 2017”

24/01/2017 - Speeches

“The risks and prospects

for the global economy and capital markets in 2017”

Keynote address by

Professor John (Iannis) Mourmouras*

Deputy Governor, Bank of Greece

at AMUNDI - OMFIF Asset and Risk Management Seminar

entitled “Risk and yield management for official asset managers in a multicurrency system”

London, 24 January 2017

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Today, as policies and capital markets seem to be moving from the “Unconventional Era” and “Great Distortion” towards “Gradual Normalisation”, I would like to discuss not only the prospects, but also the challenges we face head-on.

Let me start by offering my own insights into the global market outlook.

1. GLOBAL ECONOMIC OUTLOOK FOR 2017

The world economy

2017 will be very different from 2016, in many respects. If 2016 will be remembered as the year of Brexit and Donald Trump’s election, 2017 I foresee may well be remembered for developments in the European continent. I refer to the national elections and the associated political uncertainty that may trigger further changes in the eurozone and the broader European Union, as we know it today. Two other key topics will be the new US economic policy under President Trump and the end of the dominance of central banks, which will pass the torch to fiscal policy across the globe.

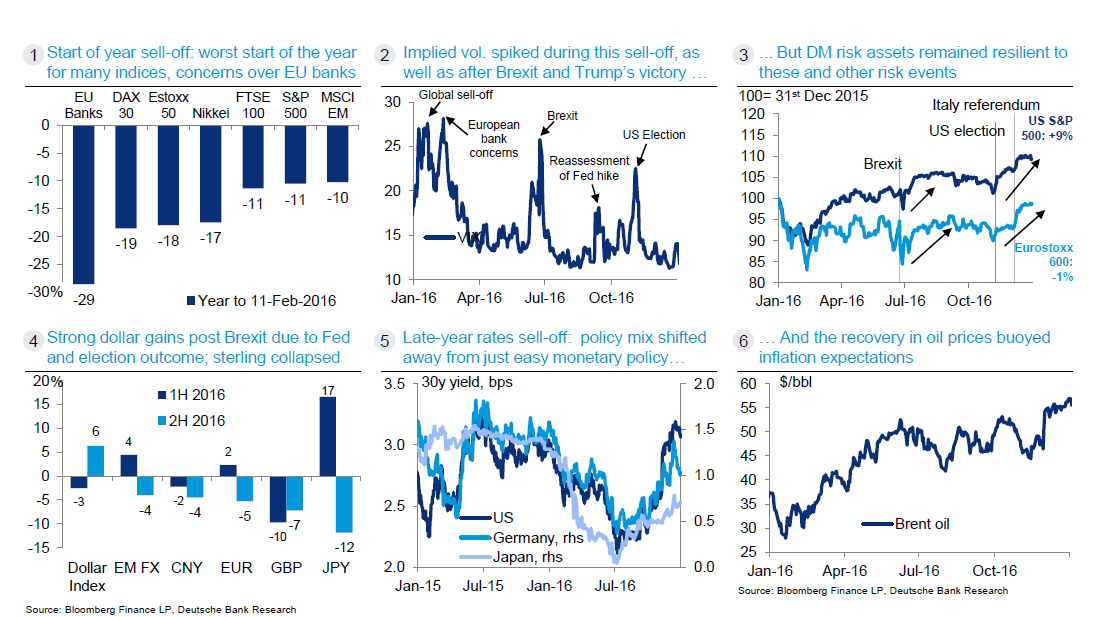

In 2016, performance in the world’s major capital markets has been low by historical comparison, reflecting the salient events over the course of the previous year. I will show you only one figure depicting 2016 in six charts and refrain from any further comments about last year, as the Bank of England’s Chris Salmon will provide a thorough overview of financial market developments in 2016 later this evening.

Figure 1. 2016 in six charts

The IMF’s latest macroeconomic projections, released last week, suggest that recovery is on the way1 this year once again. A pick-up in global real GDP growth is expected, from 3.1% in 2016 to 3.4% in 2017, driven mostly by a rise in emerging markets’ growth (4.1% in 2016 to 4.5% in 2017) and secondarily by a pick-up in advanced economies’ growth (1.6% in 2016 to 1.9% in 2017) (see Figure 2). Also, headline consumer price inflation in advanced economies is forecast to increase to 1.7% in 2017, up from 0.7% in 2016, mainly on account of higher oil prices and in line with the rebound in world economic activity.

Figure 2. Real GDP growth (year-on-year) in major economies

%20in%20major%20economies.png)

The most astonishing fact about the world economy is that it has grown every single year since the early 1950s. It has very rarely grown by less than 3% since the early 1950s and only four times by less than 2% - in 1975, 1981, 1982 and 2009. The first three were the result of oil price shocks, triggered by wars in the Middle East and Federal Reserve disinflation. The latter was caused by the Great Recession after 2008’s global financial crisis.

The following slides summarise the IMF’s January predictions for this year about the major blocks of the world economy. Let’s start with the US.

The US outlook

Output growth is projected to rise to 2.3% in 2017 and 2.5% in 2018. Both business and consumer confidence are at their 15-year peak, suggesting that the US economy is buoyant at the end of the Obama administration. In addition, after the latest FOMC meeting, the Fed’s expectations for CPI inflation in 2017 are at 1.8%-1.9%, slightly higher than the previous forecast of 1.7%-1.8%.

The eurozone outlook

Focusing on the economic developments in the euro area, the economic sentiment indicator for the euro area rose to 107.8 in December 2016, reaching the highest since June of 2011, while consumer confidence remains at negative territory of -5.10, but in the highest level the last 20 months. As far as inflation data concerned, according to Eurostat’s flash estimate, annual HICP inflation had continued to rise in December 2016, to 1.1%, after 0.6% in November, while core inflation (flash estimate) increased to 0.9% in December, up from 0.8% in November. Inflation expectations, as measured by the five-year inflation-linked swap rate, edged up to 1.77% at the beginning of December, close to the values recorded at the beginning of this year, slightly higher than prior to the start of the PSPP last year. Moreover, the December 2016 Eurosystem staff projections foresee the euro area HICP inflation at 0.2% in 2016, and 1.3% in 2017, while real GDP growth is foreseen at 1.7% in both 2016 and 2017 and at 1.6% in both 2018 and 2019, broadly unchanged from previous estimates.

The UK outlook

As far as the UK is concerned, stronger-than-expected performance during the latter part of 2016, led the IMF to revise upwards its real GDP forecasts for 2017 to 1.5%, from 1.1% previously. The average forecast for UK growth in 2017is now just 1.3%, down from 2% in 2016 and 2.2% in 2015. This reduction is due to the forecast impact of Brexit. But the average conceals a wide range underneath. At the optimistic end, growth is predicted to reach 2.7% while, at the pessimistic end, it is predicted to be just 0.6%. But the majority of forecasters seem to expect a significant slowdown next year a hard UK exit from the EU in 2019 is now a plausible scenario. Due to concerns over the general economic outlook, consumer spending is expected to slow significantly in 2017, amid weakening fundamentals.

Living standards are also likely to fall, after two relatively good years. One reason is the slowing economic growth. This would mean declining growth of employment and possibly an outright decline. Furthermore, weak sterling and rising inflation will erode real wages. Growth of real earnings is forecast at around, or below, zero in the second half of 2017. High inflation will also aggravate the freeze on the nominal value of welfare benefits. A number of other factors may give rise to downside risks for the UK output. First, the UK is running an enormous current account deficit, forecast at 5.7% of GDP in 2016. Second, public sector net debt is forecast to hit 90% of GDP in 2017-18, which suggests a diminishing margin of manoeuvre. Third, productivity growth remains too weak. Finally, business investment remains too weak to shift the adverse productivity trend. The consensus of forecasters for consumer price inflation in 2017 is 2.5%, up from a mere 0.7% in 2016.

The Japan outlook

With regard to the Japanese economy, IMF has also revised upwards its real GDP forecasts to 0.8% for this year and to a relatively stable pace of around 1% in the years to come. According to the Bank of Japan, this is a rather moderate expansion with rising domestic demand, based on a rising domestic demand large-scale fiscal stimulus and growing exports. Inflation in Japan remains close to zero, almost four years after the Bank of Japan began an enormous monetary stimulus, as low oil prices and a period of yen strength dragged down prices. “The year-on-year rate of change in the consumer price index is likely to be slightly negative or about 0% for the time being,” said the Bank of Japan.

Emerging market economies (EMEs)

As regards emerging economies, economic activity is projected to reach 4.5 percent for 2017, around 0.1 percentage point weaker than previously forecasted. China’s economy is expected to have met the government’s target of at least 6.5% growth of GDP for 2016. It is expected to continue to grow at a slightly slower rate (6.2%) also next year. Two main risks are threatening such a robust economic performance by the Chinese economy, which, if materialized, will result in a sharp slowdown in the Chinese economy, will have effects that will be felt globally. Commodity exporters, like for instance Brazil, Australia and South-East Asia, would then be hardest hit. The first one arises from the high level of debt overhang. China’s total corporate debt load had reached 255% of GDP by the end of June, up from 141% in 2008 and well above the average of 188% for emerging markets, according to the BIS. The second one is China’s troubled shadow banking system, which lacks financial sophistication. They look at the yield, and they don’t pay attention to the risk. A hypothetical series of defaults would shatter the assumption of an implicit guarantee, sparking a run that would leave dozens of banks exposed to a funding crisis.

Finally for 2017, watch out for India, which by the way marks 70 years since its independence from the British Empire. For the past two consecutive years, India has outpaced China in terms of growth rates and is expected to do so this year as well. The growth forecast for 2017 is 7.2%. Indeed, India seems to have gained a momentum despite the temporary negative consumption shock induced by cash shortages and payment disruptions associated with the recent currency note withdrawal initiative.

Table 1 Real GDP and CPI Forecasts for Major World Countries

|

Indicator

|

Real GDP (YoY%)

|

CPI (YoY%)

|

|

Year

|

2016

|

2017

|

2016

|

2017

|

|

United States

|

1.6

|

2.3

|

1.3

|

1.9

|

|

Japan

|

0.7

|

0.8

|

-0.2

|

0.0

|

|

Euro Area

|

1.7

|

1.7

|

0.2

|

1.3

|

|

UK

|

1.3

|

1.5

|

0.7

|

2.5

|

|

China

|

6.5

|

6.2

|

2.0

|

2.2

|

|

India

|

6.6

|

7.2

|

5.0

|

4.7

|

Source: IMF, ECB, Fed, Bank of Japan, Bank of England, and Bloomberg.

2. RISKS TO THE GLOBAL ECONOMIC OUTLOOK

A. US policy uncertainty due to new fiscal and trade policy

In the final months of 2016, financial markets responded to Donald Trump’s election in textbook fashion - not only at asset class level, with upward movements in stocks and government bond yields, but also within asset classes. Markets were responding to prospects for higher growth, inflation and market inflows following the US president-elect’s policy announcements on deregulation, tax reform and spending on infrastructure. Even more impressive, this occurred in a remarkably orderly fashion, with little evidence of distress among investors.

Trumponomics will remain an important market influence this year, with investors particularly interested in two things: the transition from announcements to detailed design and sustained implementation; and outcomes, particularly when it comes to the mix between higher growth and inflation. The anticipation of a more active fiscal policy is based on the assumption that President Trump will reinvent the package of policies known as Reaganomics. Not without reason. Most importantly, during much of his first administration loose fiscal policy collided with a tight monetary stance as Paul Volcker’s Federal Reserve sought to squeeze inflation out of the system. This resulted then in a seriously overvalued dollar.

The strength of the dollar since the Trump election is justifiably based on that historic analogy. It seems that there are two differences, however, between the Reagan administration and the Trump one. Reagan was fortunate in taking office in 1981 just after the second oil crisis tipped the economy into recession. As well as a strong cyclical recovery, the economy received a windfall as the oil price collapsed. As inflation came under control, policy interest rates came down, laying the foundation for a 35-year bond bull market.

President Trump, by contrast, makes his entrance at the tail-end of a mature, though fragile, expansion. Wages are rising and there is little slack in the economy. On some estimates, the potential growth rate is as low as 1.5%. In other words, the risk of witnessing more inflation than growth is real. Secondly, there are debt levels. Reagan started a long surge in public-sector debt. Yet gross public debt today, at nearly 105% of GDP, is more than twice its size when Reagan left office in 1989 - a level not seen before outside the context of war.

On the external front, there is the question of foreign policy, both in terms of trade and geopolitical issues. There is a heightened risk on “trade protectionism” under the Trump administration. For several Asian economies, as well as Canada and Mexico with strong trade ties to the US, including the emerging markets, open borders and free-trade agreements are of paramount importance. But also, for the rest of the world, protectionism will have serious implications that will impact on the performance of their economies. Overall, a surge of protectionist measures would not only undermine the recovery in global trade, it would also disrupt global supply chains and limit international factor movements, for both labour and capital. A protectionist backlash would not just have an adverse near-term cyclical impact, but also a negative long-term structural impact on potential growth.

Finally, two cautious remarks on the US economy: (1) A skyrocketing dollar may inhibit growth. The dollar is up 25% against the euro since 2014. (2) The recent big fall in real US yields (for 10-year Treasury notes to 0.38% today, from 0.74% one month earlier) may suggest that investors moderate their expectations for Trump’s economic agenda. Clearly, when optimism towards the economy brightens, investors typically demand a higher real yield to hold treasury debt, and the reverse also holds.

B. Europe’s politics

Political risks to the European order are on the rise after the UK vote to leave the EU and the unprecedented wave of migration from war-torn countries in the Middle East and North Africa that has fueled the rise of nationalist politics and populism and a backlash against mainstream politicians and political and financial elites. Euroscepticism is now a strong sentiment in Europe. Populist parties are in government or in a ruling coalition in nine (9) countries of the EU. This is an alarming figure. Elections this year in the Netherlands, France, Germany, and maybe Italy, four of the founding members of the European Economic Community back in the 1950s, are critical as they may provide gains to populist parties that would result in increased Euroscepticism across Europe and as political risks seem to come ahead of economics. But what exactly does populism mean? And why markets should care about it? There are three reasons. First of all, there is anti-globalism and blaming of free-trade agreements and global finance. Second is an embrace of state activism in the economic field, which implies less structural reforms, undoubtedly inhibits long-run growth and, in turn, jeopardises public debt sustainability which is at the heart of the south of Europe’s economic troubles. Third, populists are averse to policymaking based on rules and in favour of discretionary policymaking and interventionist policies.

In short, the risk with the multiple elections and possibly a mushroom of referenda in Europe is that we cannot rule out that voters will once again turn against the mainstream parties, shifting towards less international cooperation, away from free trade and away from open borders and migration. Brexit is perhaps the best example. Prime Minister May’s powerful speech on 17 January set the agenda for a hard Brexit, on the ground that no deal is better than a bad deal, regardless of the short-term cost to the economy. Effectively, the Prime Minister will not seek for the UK to remain in the single market, but will negotiate a customs agreement and, in exchange, regain control over UK borders. Hopefully there won’t be any upsets and further complications from today’s decision by the Supreme Court of Appeal on whether the UK government can formally initiate Article 50 without parliamentary approval [the High Court has ruled that parliamentary approval is required]. If Article 50 is triggered in March I hope that at least part of the negotiation will be careful not to jeopardise the City of London’s role as a leading global financial centre.

C. Geopolitical and other risks

A third set of risks is geopolitical. To name briefly a few, the coming friction between President Trump’s US and China, but also Germany; friction between Iran and Saudi Arabia, and the real threat of ISIS hitting Western democracies.

Last but not least, underlying vulnerabilities remain among some large emerging market economies, with high corporate debt, weak bank balance sheets, and thin policy buffers, implying that these economies are still exposed to tighter global financial conditions, capital flow reversals, and the implications of sharp depreciations, especially as a result of an unprecedented strength of the US dollar. All this heightens their exposure to severe external shocks. Indeed, the last time emerging economies faced monetary tightening and fiscal loosening in the US (in the early 1980s), many of them (notably in Latin America) slid into a lost decade.

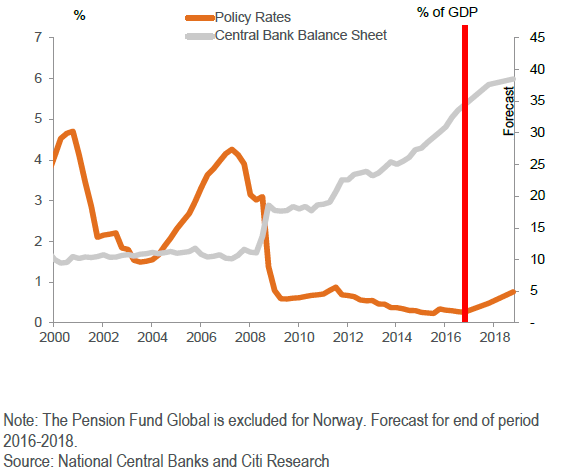

3. CENTRAL BANKS’ MONETARY POLICIES

In the beginning of 2017, it seems that the major advanced economies monetary easing cycle may be ending soon. Since August 2007, the average advanced economies’ policy rate has fallen by 377bp, ranging today from -0.75% in Switzerland to +1.75% in New Zealand. In addition, advanced economies’ central bank balance sheets have expanded dramatically, from an average of 11% of GDP in mid-2007 to 34% of GDP by end-2016. Balance sheet increases were largest in Japan (from 22% of GDP to 91%) and Switzerland (19% to 111%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Advanced Economies’ - Quarterly Average Policy Rate (%) and Central Bank Balance Sheet Size (% of GDP), 2000-2018 (Forecast)

Fed

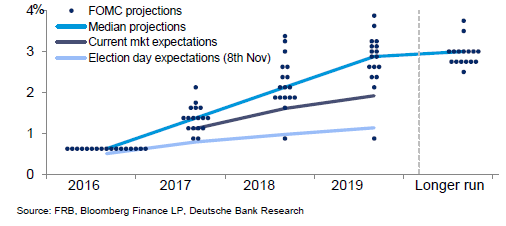

In response to the US’s strengthening labour market and moderate expansion in economic activity, the Fed announced last December its widely anticipated increase in the federal funds rate target to 0.5%. The Fed has indicated that future increases would soon follow, possibly three times by the end of 2017.

Federal Reserve Bank president Janet Yellen suggested that the Fed would need to “have time to wait and to see what changes occur” under President Donald Trump’s administration to factor those into the Fed’s future decision-making. At present, markets are priced for only two rate increases this year, one in the end of the first half of 2017 and another by the end of the year, while the market-implied probability for a rate hike in March is around 25% (Figure 4).

Figure 4. FOMC projections and current market expectations

In short, the Fed probably will not alter its gradual monetary normalisation plans until there is more clarity about the profile of US fiscal policy.

ECB

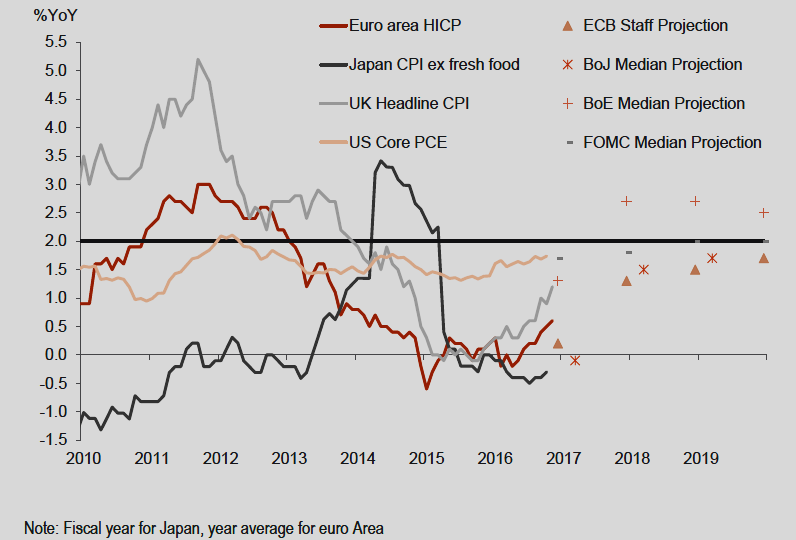

It is true that the critical indicator for the ECB remains core inflation. Indeed, core inflation has been incredibly persistent in the euro area, stuck below 1%, while inflation forecasts until 2019 remain under the target with downside risks, as I said earlier. Hence, at least for the first half of the year, the ECB’s stance remains accommodative as more evidence that inflation is self-sustaining is needed. Against this background, taking into account that, as I predict, the Fed will continue its monetary policy normalisation by raising key policy rates gradually, the so-called monetary policy divergence among G-4 central banks will remain a key theme in the 1st half of 2017.

However, higher oil prices could feed into a gradual increase in inflation, (Figure 5). When inflation expectations are on the rise, the ECB’s forecasts could soon point to opportunity for the ECB to rebalance its stimulus by tapering QE and rely more on liquidity provision. Hence, any upcoming reductions in the APP could be seen as a gradual tapering. In this context, communication will be crucial, while to protect the periphery from what may be seen as a reopening of credit risk (sovereign debt is substantial), banks may be given another liquidity injection (TLTRO). We all recall the financial market effects from the Fed’s tapering in spring 2013, which largely contributed to a sell-off that drove the 10-year Treasury bill from just above 1.60% in early May 2013 to 3% only four months later.

Figure 5. Euro forward inflation linked swaps (1-year-1-year & 5-year-5-year)

.png)

Source: ECB.

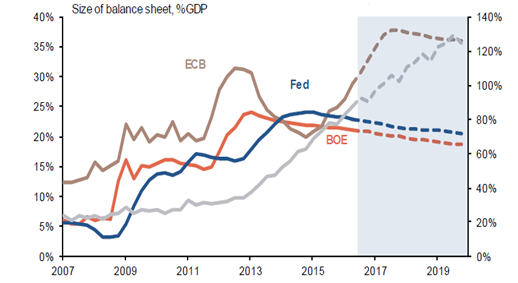

In the eventuality of such QE tapering, less monetary divergence between G-4 central banks will be on the cards for the second half of the year (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Less QE from ECB, less monetary policy divergence

Source: US Fed, Bank of Japan, ECB, and SG Cross Asset Research/Global Asset Allocation.

Source: US Fed, Bank of Japan, ECB, and SG Cross Asset Research/Global Asset Allocation.

Bank of Japan

As you know since last September the Bank of Japan introduced a new monetary policy framework best known as “QQE with yield curve control” and shifted its key policy target from quantity (i.e. asset purchases) to interest rates, thus preparing the ground for its own QE tapering. While inflation is likely to remain much lower than the Bank of Japan’s 2% inflation target in coming years, (2017 Forecast: 0.6%), it is not expected by the markets any more monetary easing during Governor Kuroda’s term (ending in April 2018).

Bank of England

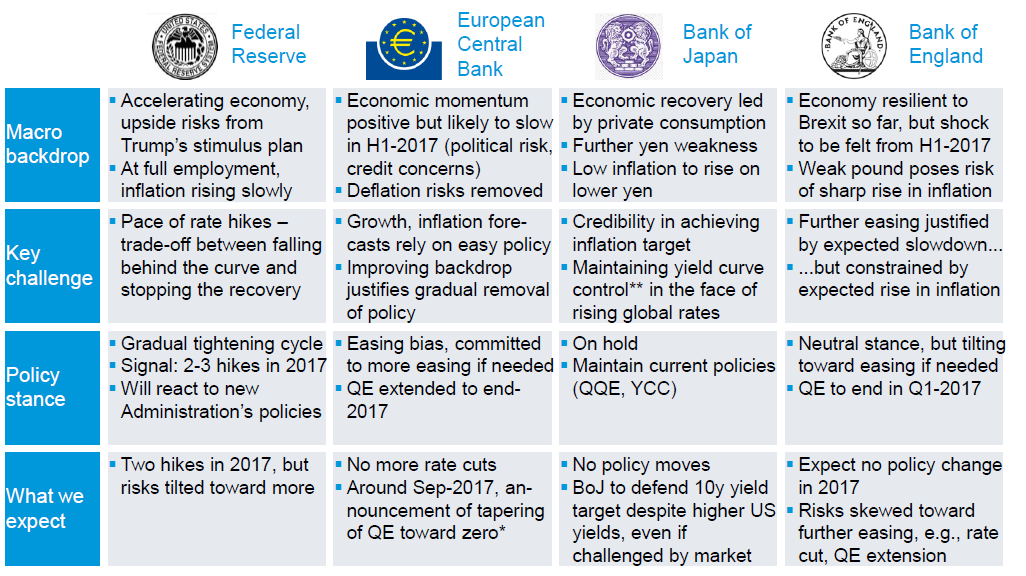

Although spot inflation will likely move higher over the coming year, (according to BoE’s forecasts, inflation will rise to 2.7% in 2017), the BoE has clearly stated that its stance now is neutral. However, there are enhanced concerns over the impact of the Brexit referendum on growth, together with the potential shock to real incomes expected as price pressure begins to build over Q1. At present, the market prices a 35% chance of a 25bp rise to Bank Rate by the end of 2017. Finally, Table 2 shows in detail the monetary policy front from the G-4 central banks in the year ahead and Figure 7 shows their median inflation forecasts.

Table 2. Fed, ECB, BoJ, BoE monetary policies in 2017

Source: Bloomberg.

Note: 1.The ECB announced that QE purchases would continue beyond March 2017 until end-2017, at €60 billion per month (dropping from €80 billion currently). Purchases are unlikely to stop altogether at that stage; rather, the ECB would announce a gradual phasing out of QE. 2. YCC: 10-year yield target of zero, negative policy rate.

Figure 7. CPI Inflation (% YoY) and Central Bank Median Inflation Projections, 2010-2019

Source: Bank of Japan, ECB, US Federal Reserve, Bank of England, and Bloomberg.

In a nutshell, my verdict on monetary policy in the year ahead is: more monetary policy divergence in the first half and less monetary policy divergence in the second half of the year, which, in terms of the financial market’s jargon, means less distortion from unconventional monetary policies, a gradual return to monetary policy normalisation and steepening yield curves.

4. FINANCIAL MARKETS PROSPECTS IN THE YEAR AHEAD

A. THE US DOLLAR DOMINATES FOREIGN EXCHANGE MARKETS

I turn now to foreign exchange (FX) prospects for 2017. 2016 was the year that shook up currencies: sterling took a beating, while the dollar continued to march ahead; in real effective terms it has appreciated by more than 6% since August (Figure 8). This year it is predicted that the dollar will once again dominate the FX markets.

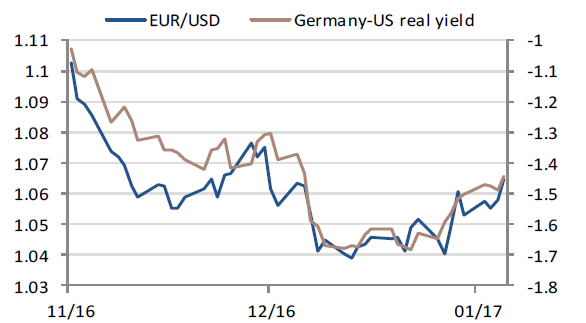

- Against the euro: Parity is on the way

The main question is: How far can the USD run? The extent of monetary divergence between the Fed and the ECB will be the major driver for US dollar strength, together with a higher-than-expected budget deficit as a result of fiscal stimulus, which with higher long-term government bond yields will attract new capital inflows. In addition, a busy electoral calendar in Europe will be another source of concern for investors in light of the recent rise of populist movements and euro scepticism as the European political agenda looks busy in 2017. As a result, the dollar’s strength is expected to remain with the euro against the dollar to move near to parity and could break it by year-end.

Figure 8. EUR-USD and real yields

Source: Bloomberg.

- Against the British pound: The Brexit risk overshadows everything

The US dollar rose against the pound by more than 16% on a yearly basis last year. Downside risks for sterling remain significant this year, while periods of spikes are expected considering the recent sterling behavior after Prime Minister Theresa May $ announced the UK’s hard-line negotiating position. On Tuesday, 17 January, right after Prime Minister May’s speech, the sterling rose by almost 3% against the US dollar and by 2% against the euro, recording its biggest gains against the US dollar since 1993, to above US$ 1.24 (Figure 9).

Figure 9. GBP-USD Spot Exchange Rate (above) and GBP-USD 3-month ATM Implied Volatility

%20and%20GBP-USD%203-month%20ATM%20Implied%20Volatility.gif)

Source: Bloomberg.

- Against the yen: further appreciation ahead

As the market is expecting a notably more restrictive US monetary policy, whereas the Bank of Japan will remain rather expansionary, the outlook for both USD-JPY and EUR-JPY currencies is to appreciate during this year.

- Against CNY: Weakness abroad

The CNY has depreciated by more than 3% against the US dollar since the SDR inclusion in October and by around 10% on a yearly basis. A managed depreciation remains the key theme for the CNY in the foreseeable future as one of the Chinese authorities’ priorities is the currency credibility due to China’s aspirations for the CNY to become a global reserve currency.

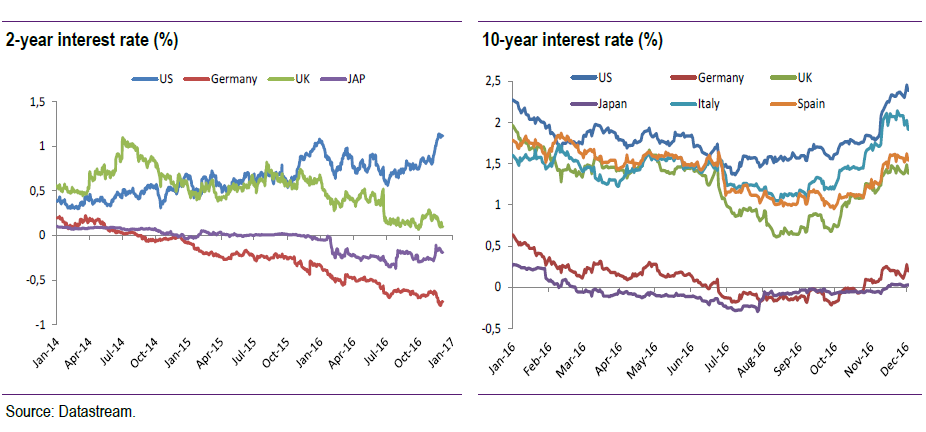

B. Sovereign bonds: more than usual volatility / rebuilding term premia/ steepening yield curves

As the global policy mix is evolving towards more fiscal easing and less monetary easing, there is intrinsic uncertainty because effective implementation of such a policy shift is still very much an open issue. This would lead to higher yields, more volatility and higher term premia, especially on the long-end of the yield curve, which is overbought over the last few years due to low-for-long interest rates (Figure 10). As a result, the themes of rebuilding term premia in long maturity rates and steepening yield curves are gaining ground.

Figure 10. Interest rates on, 2-year and 10-year sovereign bonds in the US, Germany, Italy, Spain, Japan, and the UK

US government bonds market

Increasing term premia effectively means that there is room for a steeper yield curve for a given level of short rates. The degree of US government yield curve steepening will depend on the pace of policy normalisation by the Fed, on the depth of tax cuts and the level of infrastructure spending. All this could lead to higher inflation expectations and a sharp repricing of term premia.

Euro area government bonds market

The outlook for European fixed income in 2017 requires a careful balancing act between expectations of less monetary policy support on the one hand and structural factors, on the other hand, such as unresolved banking sector issues as well as political developments (Figure 11).

Figure 11. US-German Government 2-year and 10-year bonds spread (in basis points)

.png)

Source: Bank of Greece and Bloomberg.

Any widening in periphery spreads will depend on country-specific politics, the long-standing issue of economic non-convergence, but also given that the ECB’s APP will run throughout the year. Hence, a rise in the yields in the europeriphery is quite likely and the spread between core and peripheral yields will fluctuate throughout the year.

Finally, one word about equities. Watch out once again for the correlation between bond yields and returns on equities. Since the 2008 crisis, this correlation has been systematically negative due to drastic non-standard measures with a few exceptions (Fed’s tapering in 2013 and the Bund tantrum in 2015, during which bonds and equities prices abruptly corrected). In my view, the bond-yield/equity market correlation will remain negative as a trend once more this year, albeit less pronounced and more volatile (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Interest rate/ US equity market correlation (26-week moving average) vs. Fed cycle

%20vs.%20Fed%20cycle.png)

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Thank you very much for your attention!

*Disclaimer: Views expressed in this speech are personal views and do not necessarily reflect those of the institutions I am affiliated with.

1 IMF, World Economic Outlook, January 2017.

Appendix

Mid-year update (28 July 2017)

A. Global economic outlook

1. Global growth: In the first half of 2017, global financial market conditions have been benign and benefited by improving market expectations about growth in the world economy and easing political concerns. 2017 is a pivotal year as it should mark the end of additional monetary easing measures by the world’s major central banks. There are a lot of downside risks for the rest of the year, but look more balanced in the near term. According to the World Bank’s latest forecasts, global GDP growth is expected to accelerate to 2.7% in 2017, from 2.4% in the previous year, and reach 2.9% in 2018, while global trade growth has rebounded from a post-crisis low of 2.5% in 2016, despite rising trade policy uncertainty. World trade volume is expected to increase by 4.0% in 2017, compared with 2.5% in the previous year. If this rate is confirmed, it will be the highest since 2011, but still significantly below the long-term average.

2. US outlook: GDP growth (1.2%) was disappointing in the first quarter of 2017. The optimism expressed at the beginning of the year has thus remained confined to willingness rather than action, an observation that also applies to the political sphere. Despite more than 60 executive orders and memoranda signed by Donald Trump, few major decisions were taken in his “first 100 days”. The beginning of his presidency has, above all, unveiled the divisions within the Republican Party, which despite its majority in the Senate and the House of Representatives is struggling to deliver on the reforms it promised. Therefore, output growth is projected to reach 2.1% in 2017 and 2.2% in 2018 (1.6% in 2016), much lower than Trump administration’s plan to get the economy growing at 3%, while CPI inflation was revised downwards by the Federal Reserve (Fed) at 1.6% in 2017 from 1.9% previously.

3. Eurozone outlook: The eurozone confirmed the strength of its economic recovery in 2016 by posting a growth rate of 1.7%, well above its potential for a third year in a row and faster than the United States for the first time since 2008. GDP growth in Q1 2017 was at 0.6% quarter-on-quarter. Ultimately, growth is expected to average 1.9% in 2017 and 1.8% in 2018. Indeed, several political and economic developments should support growth. As far as inflation is concerned, annual HICP inflation decelerated to 1.3% in June 2017, down from 1.4% in May, while core inflation rose to 1.2% in June from 1.0% in May. Looking ahead, the outlook for HICP inflation based on Eurosystem staff projections has been revised downwards, mainly reflecting lower oil prices, to 1.5% for 2017, 1.4% for 2018 and 1.6% for 2019.

4. UK outlook: The UK economy has now grown for 17 consecutive quarters and remained resilient over the three quarters following the Brexit referendum, despite headwinds from the vote for the UK’s exit from the European Union. However, quarterly real GDP growth rate fell to 0.2% in the year to the first quarter of 2017, from 0.7% in the fourth quarter of 2016, the slowest in two years, primarily as a result of a softening in consumer expenditure and the services sector. On the inflation front, pressures continued to build as CPI inflation rose to 2.9% in May from 2.7% in April, the highest in around four years, significantly above the 2016 average rate of 0.7% and also well above the Bank of England’s 2.0% target. Therefore, the UK’s GDP growth rate is expected to reach 1.9% in 2017 and 1.7%, 1.8% for 2018 and 2019 respectively, while according to the Bank of England’s expectations inflation could rise above 3% by the autumn of 2017, and is likely to remain above the target for an extended period.

5. Japan: With an annualised quarterly growth rate of 2.2%, Japan’s GDP recorded positive growth for the fifth consecutive quarter in early 2017 - something that had not happened in more than ten years. Continued accommodative monetary and fiscal policies should support growth, projected to edge up to 1.8% in 2017 and 1.4% in 2018, as the effects of the fiscal stimulus wear off. The Bank of Japan’s policy shift in 2016 to targeting long-term interest rates around zero is expected to keep interest rates at low levels, as core inflation is projected to stand at 1.1% in 2017 and 1.5% in 2018, still short of the 2% level it targets.

6. EMEs outlook: From a post-crisis low of 3.5% in 2016, growth is projected to strengthen to 4.1% in 2017 and reach an average of 4.6% in 2018-2019, reflecting a recovery in commodity exporters, while growth in commodity importers is projected to remain robust. Chinese economic activity accelerated in the first quarter of 2017, following a 2016 fiscal year of remarkable stability and is projected to remain near 6.7% in 2017 and 2018, partly thanks to the impact of earlier fiscal and monetary stimulus. However, risks from financial vulnerability still persist, mainly including the debt overhang in the corporate sector and rampant shadow banking activities. Growth in commodity exporters will continue to accelerate, from an estimated 5.1% in 2017 to its long-term average of 5.3% in 2019. Among them, the Russian economy has returned to positive growth readings and Brazil is expected to also return to positive growth rates after a 2-year recession.

B. RRR: Rethinking risks and returns in capital markets

1. Central banks’ monetary policies: the Fed is expected to raise once or twice its policy rate by the end of the year and announce the start of balance-sheet shrinking at the next meeting of the Federal open Market Committee (FOMC) in September. For the ECB, its accommodative stance on monetary policy is set to continue as Draghi mentioned in the ECB Governing Council’s meeting in July: “a very substantial degree of monetary accommodation is still needed for underlying inflation pressures to gradually build up and support headline inflation developments in the medium term”. However, it is widely expected that the ECB will introduce forward guidance on tapering at the annual central bankers’ symposium in Jackson Hole, from 24 to 26 August. However, there is still a large part of uncertainty on the sequencing of the ECB’s exit strategy, namely whether to move away from negative rates and then follow with the process of QE tapering or to move towards interest rate hikes only after QE tapering is fully completed, as the Fed did recently.

2. Potential risks ahead: Short-term risks are broadly balanced, but medium-term risks are still skewed to the downside, inter alia: increased protectionism and trade retaliation which would harm growth, as deteriorating trade relationships between major economies could weigh on confidence and derail the ongoing recovery in global growth; a more protracted period of policy uncertainty which could harm confidence, deter private investment, and weaken growth; and finally potential financial tensions which could trigger a correction in rich market valuations, especially for equities, and a sharp increase in financial market volatility from current low levels.

3. Bond markets: The unwinding of central bank accommodation remains very challenging. The global economy is stronger than a year ago, while inflation has also picked up globally, albeit from low levels. The Fed’s further monetary policy normalisation and the ECB’s potential forward guidance on tapering asset purchases justify a bearish outlook on bond markets and higher global term premia.

- US: Although there is significant uncertainty on US fiscal and monetary policy outcomes, a modest rise in US Treasury yields is expected by year-end. The continued rise in the US federal funds rate and the moderate reduction in the Fed’s balance sheet should lead to a flattening of the Treasury yield curve. Hence, 10-year Treasury note yields may gradually rise to 2.70% by end-2017, with risks titled to the downside.

- Eurozone: Prospects of inevitable QE tapering sooner or later should continue pushing up eurozone fixed-income term premia, as the future path of policy normalisation becomes more data-dependent. In short, the 10-year German Bund yield could reach 0.60%-0.70% by year-end.

- Greece: The country returned to bond markets for the first time since 2014, pricing €3 billion of new five-year bonds with a coupon rate of 4.375%, yielding 4.625% and attracting more than €6.5 billion in orders. This new bond issue could help Greece not only to build up a proper yield curve which is a necessary tool for active debt management, but also cash buffers as a precautionary credit line which will enhance investors’ confidence.

4. Foreign exchange markets: Reduced political uncertainty in Europe and US economic disappointments in the first half of 2017 have halted the rise in the dollar this year. At present, the market focuses on the ECB’s potential exit from its bond purchasing programme, which would be a first step towards normalisation of the ultra-expansionary monetary policy, thus leading to a stronger euro. While investors expect one rate hike from the Fed in June and another by the end of 2017, continuing monetary tightening in the US should not put upward pressure on the US dollar. The prospect of accelerating growth and inflation, and consequently further monetary tightening by the Fed, would favour a stronger dollar only towards the end of the year. As a result, the dollar’s weakness is expected to remain and the euro-US dollar exchange rate to move towards 1.20 by year-end.

• On other major currencies: An expected range for the exchange rate of the British pound against the US dollar is between 1.26 and 1.32 {and the euro against the British pound by year-end between 0.86 and 0.94}. The expected range for the exchange rate of the US dollar against the yen is 111-114 {while an expected euro rally against the yen should allow the euro-yen exchange rate to climb towards 135}.

5. Equity markets: With global growth being synchronous, broadly-based and with none of the excesses that usually mark the very late stages of any economic cycle, the investment stance remains positive over the year-end. The only conundrum remains the very low level of 3-month correlations between equity and bond markets. It is worth simply mentioning that the last time correlations were so low was in 2007 and early 2014, i.e. both years of exceptionally low volatility.